Set adrift from economic progress

The gap between productivity and wages has been increasing for 30 years in most of the developed world, leading to jaw-dropping weatlh for some, and poverty or decreased social mobility for most. By Stewart Lansley.

One of the most significant economic trends of the last 30 years has been the way real wages for most of the working population have been falling behind the growth in productivity (the rate of increase in the capacity of the economy). As shown in the chart, between 1980 and 2007, real wages in the UK rose by an annual average of 1.6% while economic capacity grew by 1.9%. This decoupling began in the 1990s and accelerated from 2000. Since the millennium, productivity has been rising at almost twice the rate of real earnings.

The effect of this accelerating gap is that growth in the wider economy has been de-linked from rising living standards for the bulk of the workforce. In the two immediate post-war decades, the gains from growth were proportionately shared between profits on the one hand and wages on the other. Real wages and wider economic opportunities for most of the workforce moved in line with economic growth, with living standards doubling for all roughly every 35 years. That is no longer the case. Beginning in the late 1980s, wage-earners in the UK, especially those on low and middle incomes, have been set adrift from mainstream economic progress.

This widening gap is in part the result of the greater mobility of the international labour market triggered by globalisation. But it has also been fuelled by the shift from ‘welfare’ to ‘market capitalism’ initiated in the United States and the United Kingdom from the early 1980s. The liberating of markets led to a marked weakening in the bargaining power of labour - the proportion of the UK workforce in unions halved in the 30 years to 2009 - and an acceleration in the pace of de-industrialisation with a switch from middle paid skilled manufacturing to more poorly paid and less skilled service jobs.

Moreover, the growing wage-productivity gap has become a common feature of many advanced economies. In the United States, the gap has grown even more sharply, accelerating, as in the UK, from the late 1990s. In the first five years of the millennium, productivity rose by nearly a fifth while median family income actually fell. Similar, if weaker, trends can be found in other rich countries from Australia and Canada to a number of European nations. Even in Germany, a country that has travelled less far down the road of ‘market capitalism’ adopted in the Anglo-Saxon world, real wages have been frozen over the last decade.

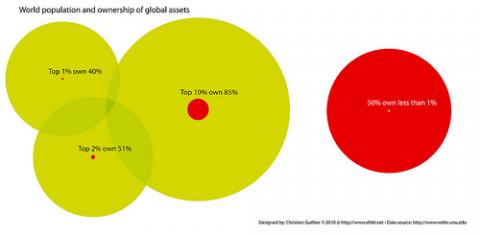

This decoupling of wage and productivity growth has had three major effects on the course of the economies most affected. First, an increasing proportion of the gains in output growth have been colonised by rising profits. It is this shift from wages to profits that lies behind the soaring personal fortunes enjoyed by a small corporate and financial elite, and the return - especially the US and the UK - to pre-war levels of income concentration.

Secondly, growth has failed to translate into expanded opportunities for all. As a result, the decoupling has halted the process of upward absolute and relative social mobility, as those on low and middle earnings have increasingly found themselves little better off (or sometimes worse off ) or with poorer work opportunities than their parents.

Thirdly, and most significantly, the growing gap has had a toxic impact on the way economies function. This is because it was the primary factor behind the soaring levels of personal debt, greater economic turbulence and mounting international liquidity that drove the global economy over the cliff in 2008-9. If productivity grows more quickly than real wages over a prolonged period, the natural process of equilibrium necessary to secure stability will be disturbed, replaced by overproduction, unemployment and recession. As real wages rose broadly in line with productivity during the 1950s and 1960s, consumer demand for the nations’ goods and services – from cars and washing machines to leisure pursuits and holidays - kept pace with their production. There was sufficient purchasing power to ensure that growing economic output would be bought, and sufficient profit to maintain the investment levels that secured growth.

The shrinking of the wage pool across most leading industrial nations over the last two decades has fractured this equilibrium. In the UK and the US, consumer demand has been maintained only by soaring levels of consumer debt, while mounting fortunes at the top have been used not to create jobs and more productive economies, but for giant speculative bets that brought booming asset prices. Hence the twin triggers of the credit crisis and the 2008 crash.

The significance of the productivity wage-gap has now been recognised at the highest levels. “The build up of widening income inequality and a reduced share of wages in national income in most countries in the decades before the crisis distorted economic growth,” the Director General of the International Labour Office, Juan Somavia, told the annual meeting of the IMF in October 2010. “Wages did not keep pace with rising productivity. In many countries growth produced too few good jobs, too little decent work. With household incomes squeezed for all but the very wealthy, growth became dependent on an unsustainable credit bubble in some countries and on exports in others.”[1]

Despite the warnings, in a number of countries, including the UK and the US, what growth there has been since the crash has been used to restore profit levels, financial sector bonuses and personal fortunes. In the US, profits have jumped by $528 billion since recovery began while wages have grown by only $168 billion. In the UK in the last 18 months, profits and personal fortunes have risen while real wages have actually fallen.[2] Indeed the wage squeeze of the last two decades is now set to tighten further. For the economy, this can mean only one thing – a continuation of the very imbalances that brought greater turbulence and triggered the second deepest recession of the last 100 years.

Stewart Lansley is the author of “Unfair to Middling”, TUC Touchstone Pamphlet, 2009 and “The Limits to Inequality” to be published in September by Gibson Square.

Notes:

[1] Juan Somavia, The Challenge of Growth, Employment and Social Cohesion, ILO, October 2010

[2] BCA Research 2011

This article was commissioned as part of May Day International, a collaboration by New Left Project, CrisisJam, Irish Left Review, Greek Left Review and Znet. Read more here.

Image top net_efekt.