Securing Africa: Post-9/11 Discourses on Terrorism

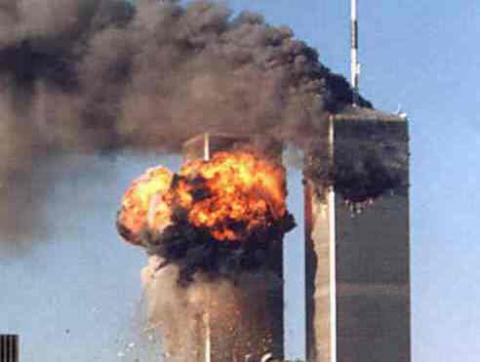

Our world is becoming increasingly uncertain. There are transnational dangers. But Securing Africa asks its readers to rigorously question dominant discourses about terrorism since 9/11. The aim of the book is to do this with Africa as a case study.

Critical thinking after 9/11, the editor contends, was silenced or slandered as traitorous. Even the Dixie Chicks bore massive criticism for their anti-war comments in 2003.

Malinda S. Smith, the editor of these essays, writes: "Critical terrorism studies call into question the ways in which some political violence is authorized and legitimized, for example, the ways in which the hegemonic status of the United States can serve to inoculate its political violence from being conceptualized under the rubric of terrorism."

She argues that, post-9/11, President Bush followed the binary thinking of Samuel Huntington – it was ‘us’ against ‘them’, ‘a clash of civilizations’. You were either with ‘us’ to protect freedom or with ‘them’ to shelter terrorism.

But Smith argues that the paradoxes of this doctrine run deep, especially when considering the constriction of civil liberties through the US Patriot Act and the Terrorist Information and Prevention System (TIPS). Phones were tapped; emails hacked. To defend freedom, it seemed, the freedom of American citizens needed to be ‘adjusted’.

The book is arguing against a spatially and temporally limitless war on terror. ‘Counter-terrorism’ is a phrase Smith wants us to question. If the definitions of terror and counter-terror are eschewed, who is the peacemaker and who is the antagonist?

The two chapters by Mustapha B. Marrouchi and Oladosu Afis Ayinde continue the explorations Smith outlines in her introduction. Marrouchi, in particular, wishes to dispel the notion that ‘we’ are rational and civilised while ‘they’ are barbaric and uncivilised. "America sees itself," he writes, "on the side of right, justice, morality, democracy, and peace. All challenges to that view are considered terrorism, unless the United States does it, whether we recall the 1986 raid on Libya by the Reagan administration in which Libya’s leader Qaddhafi lost one of his daughters or the 1998 bombing by the Clinton administration of [a] pharmaceutical facility in Sudan."

The chapters by Iqbal Jhazbhay on political Islam and Mike McGovern on Islamist practice reject simplifications of Islam as terrorism. Islamophobia, says Jhazbhay, "generated in the wake of 9/11 [...] has fed a tendency in the West toward racial and anti-Islamic profiling and stereotyping that, indeed, has helped to fuel jihadism within Muslim immigrant communities that feel marginalized and subject to persecution".

Adewale Aderemi argues that Africa lost strategic significance at the end of the Cold War. Post-9/11, this significance returned. This leads to an interesting discussion on the similarities between the Cold War and the War on Terror. Babere Kerate Chacha and Muniko Zaphaniah Marwa explore the effect of the war on terror in Kenya, while Afyare Abdi Elmi looks at Ethiopia and Somalia.

Yves Alexandre Choula examines the Project for a New American Century (PNAC). Established in 1997, the objective of the PNAC was to undermine President Clinton’s strategies. Many of the contributors to this organisation were later given important roles in the Bush Administration. For example: Dick Cheney (Vice-President), Donald Rumsfeld (Defense Secretary), Paul Wolfowitz (Under Secretary of Defense), Elliott Abrams (National Security Council), among others.

The PNAC’s website still retains the Statement of Principles written in 1997. Here, it is argued that "[A] Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity may not be fashionable today. But it is necessary if the United States is to build on the successes of this past century and to ensure our security and our greatness in the next."

For Choula, this rhetoric signified what was to come from eight years under the Bush Administration, particularly in relation to energy resources. The Gulf of Guinea was used almost as if it was territory to diminish their reliance on Arab oil states.

Choula points to the sudden projection of American benevolence towards Africa. Securing Africa involves the use of ‘soft’ power advocated by Joseph S. Nye Jnr. To gain advantages in African oil production, the United States, writes Choula, "began to employ an ethical discourse of legitimization, which emphasized governance, transparency and the promotion of development". Indeed, Bush committed significant dollars to African aid.

The final chapter, once again, by Smith, is a reflection on the early signs of continuities and discontinuities in approaches to terrorism, extremism and political violence from the Bush administration to the Obama administration.

Securing Africa is useful material for the student and academic of Africa, America and the post-9/11 world – although the index could be more substantial. The chapters are written from multiple disciplinary perspectives including political science, anthropology, philosophy, history, literature and law. The book is often informed by Michel Foucault, Edward Said and Noam Chomsky. If you find yourself gravitating toward these writers, you’ll no doubt enjoy this book. If, on the other hand, you find such authors detestable, you will probably find the book detestable.

An article by Justin Frewen on the debt burdens of African countries today can be found here.

Securing Africa: Post-9/11 Discourses on Terrorism

Securing Africa: Post-9/11 Discourses on Terrorism

Edited by Malinda S. Smith, associate professor of international relations and comparative politics in the Department of Political Science at the University of Alberta, Canada

Published by Ashgate

ISBN: 978-0-7546-7545-7