Revolt of the meritocrats

There was a time when privilege, social responsibility and public service went together. Could it return? By Andy Yee.

The Occupy movement has arrived at the elite campuses in the US, traditional breeding grounds for the one percenters. The recruiting season at Ivy League institutions, where Wall Street investment banks, consultancy, law and accounting firms attract their new bloods, face some small yet brilliant disruptions. According to theDaily Princetonian, Princeton students masked as job applicants staged protests and walkouts at the info session of Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan. At the Goldman Sachs event, students condemned the firm for trying to “mask Greek debt” and manipulating the commodity markets in 2007 and 2008 which left “a quarter million people starving”. In the J.P. Morgan event, protesters staged a recitation (YouTube video here) which blamed the bank’s “predatory lending practices” that crashed the economy. They condemned the campus culture that “whitewashes the crooked dealings of Wall Street as a prestigious career path,” and made clear that “what we need is not a university for the 1%, but a university ‘In the Nation's Service, and in the Service of All Nations’,” Princeton’s motto.

A decade ago, David Brooks went to the same university to see what the future leaders of the US, if not the world, are like. In his Atlantic Monthly essay The Organisation Kid, he writes that these future elites “work their laptops to the bone, rarely question authority, and happily accept their positions at the top of the heap as part of the natural order of life.” In a more recent essay on the same magazine, The Rise of the New Global Elite, Chrystia Freeland argues that members of the “hardworking, highly educated, jet-setting meritocrats” feel that they are “deserving winners of a tough, worldwide economic competition.” As a result, many of them “have an ambivalent attitude toward those of us who didn’t succeed so spectacularly.”

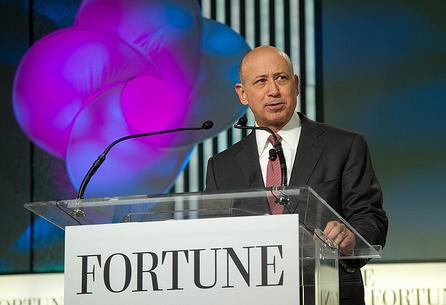

Such attitudes underpin the “winner-take-all economy” in which highly educated, highly skilled and connected elites spend much of their energies to help banks and corporations evade taxes, abuse accounting rules, manipulate markets and rig the policymaking process for their enrichment. Meanwhile, as the world is crumbling around them, their lack of self-reflection and self-criticism skills enables them to pay themselves outrageous bonuses and say that what they were doing is “God’s work”, a note struck by Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein in 2009.

2011 began with the Arab Spring, then saw the Occupy Wall Street movement and ended with Russian protests against rigged elections. While their targets are different - authoritarian rulers, Wall Street plutocrats and Russian oligarchs - they have more in common with one another than with everyone else. They are the wealthy elites with “say, an Indian passport, a castle in Scotland, a pied-à-terre in Manhattan and a private Caribbean island,” in the words of a 2007 Newsweek report, Ah, the Secluded Life. They are a transglobal community with cross-connections and dealings locked behind closed doors. If not for the Libyan uprising, such scandalous agreements as those between the LSE and Gaddafi, let alone dealings between Goldman Sachs and Libyawould not have surfaced.

In a 2010 interview given with the New Left Review, Eric Hobsbawm remarks that an important development of our age is the growing divide produced by a new class criterion, namely the meritocracy. Passing exams in schools and universities is the entry ticket into jobs and gives you a better chance of getting rich. Unfortunately, the educational system has produced a global elite class that is constantly climbing, with high self-regard and indifferent to the suffering of others. Ironically, as pointed out by Michael Young, who coined the term meritocracy five decades ago, these meritocrats can be much more smug than the beneficiaries of nepotism, because they can feel they deserve whatever they can get from their own merits.

It is instructive to contrast today’s meritocrats with those in Tony Judt’s generation, when it was still possible to think of oneself as both radical and members of an elite. In his New York Review of Books article Meritocrats, he writes that Cambridge students in the 1960s stood out in their choice of careers: “more than any group before or since, we opted for education, public service, the higher reaches of journalism, the arts, and the unprofitable end of the liberal professions,” while those who came after “resorted to the world of private banking, commerce, and the more remunerative reaches of the law.” He goes on to argue that a particular form of elitism - the incoherence of meritocracy that he was fortunate to have experienced - has been lost: one that celebrates “an inheritance of dissidence, unconvention, and unconcern for hierarchy,” “liberalism and tolerance, indifference to external opinion,” and “a prideful sense of distinction accompanying progressive political allegiances.”

As Chrystia Freeland remarks, the real threat facing the super-elite today is “the possibility that inchoate public rage could cohere into a more concrete populist agenda.” Eric Hobsbawm points out the difficulty in creating a progressive coalition between “the educated, Guardian-reading middle class” and “the mass of the poor and the ignorant”. But the deepening crisis and public outrage around the world is opening up the space for new forms of collaboration. In a satirical article published in Bloomberg which refers to Occupy Princeton, Michael Lewis addresses himself to the “Upper Ones”, saying that “the students at Ivy League schools are our most devastating ammunition in this looming cultural war.” Indeed, a cultural war has begun. The crisis which today’s meritocrats helped create has rippled back to the institutions whence they originated. Could these ripples re-awake the best of traditions of these institutions, one that is grounded in privilege, social responsibility and public service?

Originally published on Open Democracy under a Creative Commons by-nc 3.0 license.

Image top: Fortune Live Media.