Re-Intreo-ducing the workhouse

Increasingly, social welfare in Ireland is moving towards the model of the workhouse. By Tom Boland.

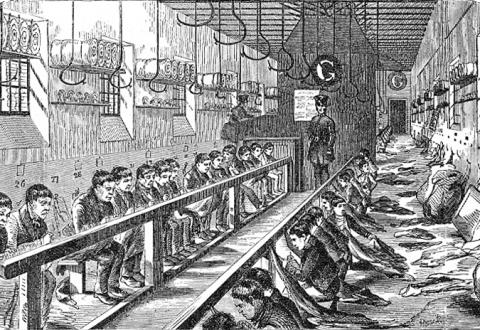

As the new year dawns we see shades of the past all around us: a man arrested for stealing bread, the return of emigration, soup kitchens throughout the country and all the while exports are booming. Another Dickensian ghost is being resurrected, under our noses; the old workhouse is re-emerging in a new guise.

In 2013 the Department of Social Protection plans to roll out Intreo offices facilitating the National Employment and Entitlements Service, which links benefits to efforts in job-seeking, as stated in the Pathways to Work policy: “In return, individuals must commit themselves to job-search and/or other employment or education and training activities or face sanction in the case of non-compliance.” If you cannot prove that you are seeking work, your benefits will be cut.

This implies that those who are not seeking work deserve less sustenance. Yet, there are few amongst us who would like to see our fellow citizens pauperised. A recent high-profile instance is where 6,500 training places were offered; those refusing to take them could face sanctions - yet some one of the hundreds of thousands on the live-register will take them, so if one refuses, another surely benefits.

It matters very greatly how we treat the unemployed: historically the workhouse was a place where those displaced from the land – either personally or in previous generations – would go to seek work, either to be met by employers or given sustenance. Without workhouses, unemployment leads to crime, riots or revolution. On the opposite pole there is the state-guaranteed income, which gives social welfare simply on the criterion of citizenship – or, in medieval society, on the basis of need.

Increasingly, social welfare in Ireland is moving towards the model of the workhouse. There are a number of reasons behind this, such as the neoliberal influence on Irish politics championed by the PDs and now commonplace. More directly, it is encouraged by the Memorandum of Understanding, which demands more vigorous labour market activation policies.

What is under scrutiny here is not the individual disposition of those who work in Intreo offices. Every institution has better and worse working for it. For every anecdote about humiliation in these offices or just recalling bureaucratic bungling, there is one of officers going to great lengths to secure benefits for people. What matters is the system – albeit that after we shape our institutions they then shape us.

The promise of the new system is alluring: “Put simply, no-one who loses his/her job should be allowed to drift, with no support, into long-term unemployment.” Of course, already no-one is; they are given welfare benefits, because that is what a civilised state does. What the new ‘support’ actually entails is a series of interventions converting entitlements into an exchange for perceived efforts.

These interventions begin with a diagnosis or profiling of the person (words which imply sickness or criminality) to assess their likelihood of drifting into long-term unemployment. Around three months the person is given guidance in job-seeking, on training and possibly group-sessions with others who are unemployed. Around six to twelve months in they are assigned a case-worker who directs and monitors their efforts to find employment or training.

Each of these steps locates the problem of unemployment with the individual, despite the larger picture of 430,000 on the Live Register and few opportunities. In such an environment, job-seeking is a Sisyphean task, with hundreds competing for positions, with little hope of even a rejection letter. It is unsurprising that 87,000 emigrated in the year to April 2012; and surely more vigorous ‘labour market activation’ policies will exacerbate that figure.

Probably, these policies will get results: As explicitly promised in leaflets for employers, the Intreo Office provides ‘Quick and easy access to future employees’. It is a system for micro-managing the supply of labour, less conspicuous than lining people up with their shovels to be picked for the days’ work. The Intreo office provides points of contact where it can pressurise the unemployed, especially where case-workers can threaten to cut benefits for ‘failure to engage with the system’. Who will be the judge of what constitutes engagement with the system, or what is suitable employment?

Pathways to Work is copied from the Australian and UK models, and sociological studies by Marston and MacDonald and Cole found that the human experience of these new welfare regimes was far from positive, leading to increased stress, self-esteem issues, depression and substance abuse. In Ireland around one-third of suicides are unemployed. Is it worth putting more pressure on people?

The shiny happy Intreo leaflets offer these dubious services and existing benefits only to those “available for work – fit for work – genuinely seeking work, but – unable to find work”. Very noble, but let us consider an alternative model. What if the unemployed simply registered themselves, their needs, their CVs with an agency that then only contacted them when they had found a suitable job? To remove the workhouse atmosphere and the duty to seek a needle in a haystack would be more humane and create better results: Let’s make Ireland the best small country in the world to be unemployed.

Tom Boland lectures in Sociology at WIT, and co-ordinates the Waterford Unemployment Experiences Research Collaborative.

Correction 04/01/2012: When originally published this piece erroneously named the author as Tom O'Connor, rather than Tom Boland. This has been corrected.