Public investment is the key to growth

Public investment is essential if the Irish economy is to get back on its feet. By Michael Taft.

Colm McCarthy’s post on Irish Economy takes a sceptical look at ‘productive investment’, or more precisely, the Government’s claim that the New ERA proposals can create up to 100,000 jobs. This leads him to state that:

“The spectre of politicians seeking to create 100,000 jobs through extra public spending is every economist’s nightmare.”

One could quip that not creating 100,000 jobs should be every economist’s nightmare. However, let’s examine what exactly a public investment-led recovery programme is intended to do. For the last thing we need in the debate is a series of assertions that sheds little light on means to kick-start recovery.

What is investment? It is the creation or upgrading of assets intended to generate income (or reduce expenditure) in the future. Through investment, we spend today to earn tomorrow. This is done at every level of society. A government invests in a modern road network to facilitate more efficient transport of people and goods; a business invests in new plant or processes to generate growth and future profits; a household invests in their children’s continuous education. All these intend to raise the productive capacity of the economy, the enterprise and individuals. There is nothing controversial in this – it is a fact of market life.

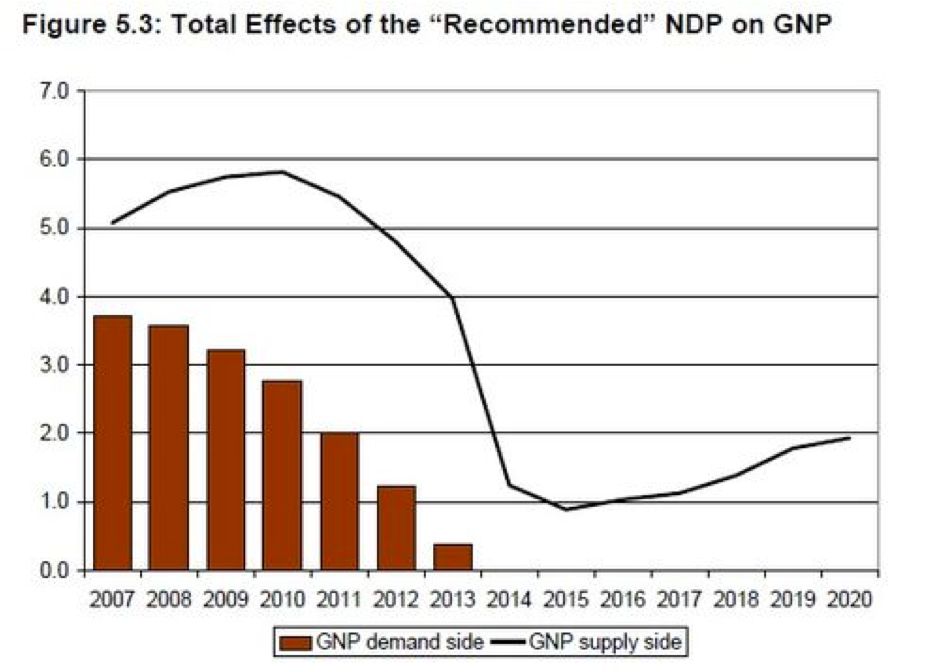

The impact of public investment is multi-layered so it is important to separate out its effects. There are, broadly speaking, two impacts: a short-term, demand-side impact which occurs when the asset is being created or upgraded. When the state invests in a modern road network, this is the activity of building the roads: directly employing people, purchasing and transporting materials, the downstream activity of more money being released (though spent wages), etc. Eventually this activity will end and the money released into the economy will filter out - this can, though, last up to six years.

The next impact however takes over immediately after the asset is created. The road is built and the economy benefits from people and goods being transported more efficiently. This is the ‘supply-side’ impact – and is the crucial part of investment. This benefit can last for years if not decades – continually adding to the economy’s productivity.

The ESRI, when examining the investment under the now-defunct National Development Plan, made and measured this crucial distinction, describing the supply-side as ‘crucial’ and as the ‘key measure’ of success.

As seen – the demand-side impact fades. However, the supply-side impact continues, dipping in the medium-term but rising again. Even after a decade the impact is felt as the economy benefits from the rate of return.

McCarthy’s criticism doesn’t take into account this long-term and ongoing benefit of investment. He assumes that investment aimed at increasing employment in the short-term (which it does) is unsustainable in its demand-side impact. But that’s obvious and nobody (at least nobody that I’m aware of) has claimed that we can keep building roads ad infinitum. The point of an investment programme is, as the ESRI has described it:

“At the heart of any extensive investment programme is an objective to boost the economy’s long-run growth potential.”

If anything, the multipliers that the ESRI used to assess the NDP programme would be even higher today – as, unlike in 2007, we have considerable excess capacity in the economy (high unemployment, under-utilised resources, etc).

McCarthy examines three sectors – energy, telecommunications and water – and doubts claims that 50,000 jobs can be created (and an additional 50,000 created through indirect or as he describes it ‘mystical’ means). Of course, we should treat political claims to job creation numbers with caution – all the more so when the current Government claims that depressing low-wages in the hospitality and retail sectors will somehow ‘magick’ up jobs, to use McCarthy’s phrase. But there is no doubting the increase in productive potential from sustained and substantial investments in these areas.

A next generation broadband network reaching every business and house in the country would create a considerable number of jobs in its ‘creation’ phrase. But the long-term impact would be even greater, especially when business in the future will require this crucial infrastructure. Access to this modern asset will promote enterprise start-ups and expansion, which in turn creates sustainable market-led job creation. And according to IBEC it would only cost €2.2 billion.

The ESB has launched a €22 billion investment programme (not many indigenous companies doing that) over the next ten years – focusing on wind, tidal, wave, biomass, geothermal and micro-energy generation. While this investment phase will create considerable jobs, the real winner would be a reduction in reliance on imported-fossil fuels. This economic benefit has the capacity to reduce future costs to businesses and households and is a more sustainable way to boost our balance of payments than depressing business and consumer imports through recession. That this comes without any cost to the Exchequer is particularly advantageous.

Thousands of jobs during the construction phases of a state-of-the-art water and waste system is a given (the Department of Finance estimates 8,000 jobs for every €1 billion spend on water services). Pursuing this investment through a National Water Company has the capacity to streamline planning, roll-out, and co-ordination, building on economies of scale. Once the network is in place, those construction jobs will end but the long-term benefit arises from (a) the savings of hundreds of millions of euros on patching together a Victorian-age network, and (b) maximising the use of a resource which will become costlier in the future.

The three examples that McCarthy uses are actually prime examples of the ability of public-led investment to substantially boost our productive capacity. But there is more:

- Pre-primary, special needs and literacy education: one of the best long-term investments we can make; and the creation of thousands of jobs (teachers, assistants, etc.) to carry out this investment.

- Retrofitting buildings to the best conservation standards: particularly labour-intensive, and with 800,000 buildings in need of such retro-fit, a long-term ‘industry’. This would also reduce energy consumption, and free up household spending for non-energy consumption.

- Urban Regeneration: the degradation of neighbourhoods multiplies social costs. Investing in livable communities creates jobs in the short-term, reduces social costs in the long-term; and, lest we forget (since investment is about building societies) raises the living standards in many communities.

I could go on – but the point is made. All the above leads to short and long-term job creation but they are mediated through demand and supply side impacts which are distinguishable and measureable.

Of course, this puts a premium on the efficiency and transparency of institutions carrying out this investment. We must put maximum emphasis on the effectiveness of such investment planning and evaluation. There are obvious and serious defects. However, there is a populist and ill-founded dismissal of the public sector’s ability in this regard. A reading of the Davy report shows that it was private, not public, sector investment that was a huge waste and an economic drain; this should put such dismissals in perspective.

To the argument that we don’t have the money – this is getting a bit tiresome. Two years ago, when the Government had over €40 billion available to it to pursue such an investment drive - in National Pension Fund assets and NTMA cash balances – we were told that we didn’t have the money. Of course, now we have fewer savings and less cash available. This is what happens when a Government pursues irrational austerity measures combined with irrational banking policies. But there are still considerable resources for investment – remaining assets and cash, interest rate reductions, accessing private pension funds for commercial infrastructural investment, establishing a Strategic Investment Bank, co-funding from the European Investment Bank, taxation on high-incomes, wealth, capital and corporate income; and, of course, redirecting subsidies from the Anglo-Irish warehouse into productive investment. And given that these investments will boost tax revenue and reduce unemployment costs we can reinvest the fiscal gains for further economic benefit. The options are there. It’s our choice.

All this leads us to a radical and viable alternative. Take a look at the ESRI chart above. The demand-side impact fades with the completion of the programme and the supply side increases start in the medium-term. Well, then, maintain the investment – continually generate new investment programmes which will maintain the demand-side impact while multiplying the medium-long term supply-side benefit.

This is the new road-map: permanent investment, sustained and substantial investment – continuously creating and upgrading economic and social assets, continuously investing in people.

{jathumbnailoff}

Image top: _sjg_.