Offaly to be the new centre of the universe

With a meagre investment of 3 million euro, Ireland could join the European-wide LOFAR radio telescope network that hopes to find, among other things, evidence for one of science’s most studied theoretical periods: the time just after the Big Bang. By John Holden.

What can you get for three million euro these days? A very fine house in leafy south Dublin? A golden handshake from AIB? Or maybe the opportunity to assist in proving the origins of the universe?

Low Frequency Array telescopes or LOFAR are a low cost form of radio telescope that has several uses. A normal optical telescope aids in the observation of objects seen with visible light. If you point a regular telescope at something – anything - you should be able to see that object’s surface up close. A radio telescope is different in that it operates in the radio frequency portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is a much lower frequency than visible light and enables the viewing of naturally occurring radio emission from stars, galaxies, and other astronomical objects. In short, it shows us a different portion of space.

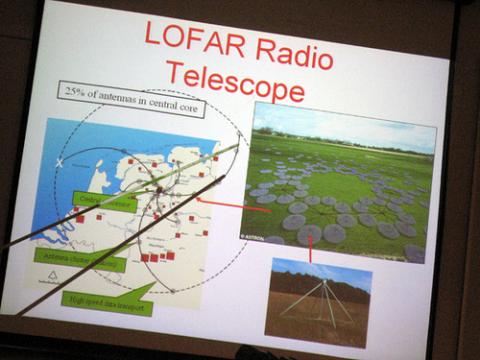

Holland currently has a nationwide LOFAR network and plans are underway to extend that network across Europe into Germany, France, Spain, the UK and possibly Ireland.

The idea for LOFAR - a real-time multiple sensor array where different sensors can be placed along a common infrastructure and made use of at the same time - was conceived in Holland in the mid nineties by Irishman George K. Miley, vice president of the International Astronomical Union at the University of Leiden. “The Netherlands has traditionally been a strong player in radio astronomy,” says Miley. “We have 36 LOFAR stations here spread across the country. LOFAR is a multidisciplinary sensor array. It looks down as well as up and besides being a radio telescope, it is a geophysical array for monitoring motions in the earth's crust below the Netherlands and helps us study the effects of gas mining here. Its technology has also been used as a test bed for studying the propagation of agricultural diseases, such as potato blight.”

We probably don’t need to be reminded of potato blight over here. But because of Ireland’s proposed site for its very own LOFAR telescope – Birr Castle Demesne in Offaly – it would actually be one of the most sensitive telescopes in the European network. Because of the geographical dip in Ireland’s midlands, radio interference from satellites, mobile phone masts etc, would be at a minimum (it would also be alongside the site of what was the largest optical telescope in the world in the 1840s).

This is very good news for those involved in the LOFAR project interested in finding evidence of the epoch of re-ionisation. This period in the early universe is believed to have taken place just after the Big Bang, when the first stars were born. “LOFAR can study radio spectral lines at frequencies below 200 MHz,” says Miley. “Re-ionisation of hydrogen will result in the emission of a line in the radio at about 1420 MHz. It is predicted to occur at an epoch in the early universe so far away that when we observe it its frequency will be several times smaller but may be observable at frequencies that LOFAR could study.”

Finding hard evidence of this period could have major implications for how we view the universe. “Scientists have predicted it, LOFAR will be able to prove it,” says TCD astrophysicist and member of the Irish LOFAR consortium, Dr Peter Gallagher.

A European LOFAR network will be a great step forward for European astrophysics but also for information communications. Every second LOFAR antennae produce 10 terabytes of data. This is the same amount of information as you would find on more than 250 DVDs (data rates are now approaching that of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider). All of this information has to be stored somewhere and that somewhere is an IBM blue gene super computer located in Germany where a distributed archive is being set up. “The real challenge will be to push all that data from Offaly back to the continent,” says Gallagher.

The problem now is finding the money to get the project off the ground. Even with a general sense that science and engineering are economic priorities, this type of science is lower down the pecking order. “We are looking for between 2 and 3 million,” says Gallagher. “We’re looking for exchequer funding and we’ve approached Science Foundation Ireland. Both are saying that they really like the proposal. But any funding available doesn’t fit into the narrow remit that Science Foundation Ireland has. There is money there but they can’t give it to this type of project.” I-LOFAR are looking to private investors who might be interested in assisting in this project. “It has a unique role to play in education,” says Miley. “The one science that inspires young children to come into science is astronomy.”

Image top: a¬a.