The more things change, the more things don't

Official and private forecasters are already revising growth projections downwards, even as they project continuing strong export growth. This is the inevitable effect of austerity on the domestic economy. By Michael Taft.

The ESRI has produced a report on deficit and debt levels up to 2015 which has moved many to claim if we just stay the austerity course we will emerge from the forest of fiscal dark into the valley of economic repose. If you haven’t yet, first read Michael Burke’s critique of the ESRI report. Here, I want to focus on a small little item (which is actually a big item): their assumptions on growth.

In one respect, the ESRI merely calculated, based on a number of assumptions, a lower level of debt interest payments and applied them to Government growth forecasts. On this, they projected the deficit by 2015. Whereas back in April the Government projected a 2.8% deficit (as a percentage of GDP), the ESRI is projecting a 1.7% deficit.

The problem with this approach is that the Government will inevitably revise their growth projections downwards going forward – and the ESRI is well aware of this. So as a static exercise, all the ESRI provides is a projection of how much we will save on the interest bill (assuming no more bank recapitalisations are necessary, we spend our cash reserves, and the banks actually return €3 billion to the taxpayer): approximately €1.8 billion less by 2015. This is useful enough. But it doesn’t tell us much about where our public finances will be.

“ . . .If growth were to prove less than assumed in the Department of Finance estimates, it would not be sufficient to stabilise the debt to GDP ratio before 2015.”

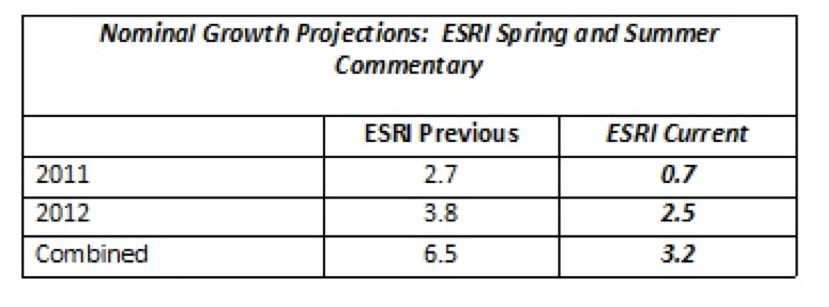

This is an all-important caveat which hasn’t got a lot of attention. So let’s look at the Department of Finance’s nominal growth projections, which the ESRI uses (I use nominal – the real GDP plus the GDP deflator – because that is measurement used in deficit and debt projections).

The ESRI assumes the Government’s projections from 2013 on, but use their own projections for this year and next – which are substantially below official estimates. In other words, their overall conclusions only work if the economy suddenly ‘jumps’ in 2013 – which is unlikely to happen.

The ESRI tried to compensate for this by assuming a 1% lower nominal growth rate. From this, they maintain the debt will still be ‘stabilised’ in 2014. This would seem to be a contradiction of their own assertion above, which categorically states that growth rates below Department of Finance estimates mean we won’t stabilise the debt.

In all likelihood growth will prove to be even more sluggish than the assumptions in the ESRI paper and the Department of Finance’s projections. The Central Bank, for instance, has revised growth downwards considerably, as has the Ulster Bank. But the most dramatic revision downwards has come from the ESRI itself.

Only three months ago the ESRI was projecting nominal GDP to grow by 6.5% over this year and next. They have now cut that growth rate by half. It is nearly 30% below the official projections. The question is – by how much more will growth rates be revised downwards before the end of the year? And, crucially, what impact will that have on growth rates going forward?

These seemingly small percentage changes could have a significant impact on the deficit. Let’s take a partial look of where we might end up, using the NCB’s recent growth projections. I’m not suggesting that they have a privileged insight – just that they are one of the few independent forecasters brave enough to project up to 2014.

NCB projects that average real GDP growth will be 2% between 2011 and 2014 compared to the Government’s (and the ESRI’s assumption) of 2.5%. This small drop in growth rates would mean that by 2014, nominal GDP falls €4.5 billion below Government projections. On average, this would mean Government revenue will be €1.5 million below target.

In other words, the fall in tax revenue (and this is a static calculation assuming that the Government’s projected revenue as a percentage of GDP holds in a lower growth environment) will wipe out the benefit from the interest rate reduction. And this doesn’t factor in any further pressure on public spending through higher unemployment and associated costs. This will subject our reduced debt sustainability ratio to considerably more market scepticism.

And this is the problem. Austerity cuts growth, which is the main driver in repairing public finances. Already, official and private forecasters are revising growth downwards even as they project continuing strong export growth. This is the impact of austerity on the domestic economy – an impact that many have underestimated.

It really is the same ol’ story with a different book cover.

{jathumbnailoff}

Image top: Phil_NZ.