Mingling business models: Ireland, Apple and China

It is rather surprising now to be reminded of the significant negative opinion that the Irish political establishment had of China in 2007. It is best illustrated by the high profile campaign calling for countries to boycott the 2008 Beijing Olympics which gained the support of independent senators, Fine Gael (in the form of Simon Coveney), Labour, Fianna Fáil and the Green Party. Contrast this with the political muscle put behind the recent visit of Chinese Vice-President Xi Jinping, or even the news this week that planning permission has been granted for a massive “Euro Chinese Trading Hub” at Creggan, near Athlone, with facilities “totalling 102, 348sq m (1.1m sq ft)”. While the computer-generated plan suggests that the designers had the phrase “Vegas, baby, Vegas” stuck permanently in their head, its size and the enthusiastic accompanying commentary from marketing experts suggests that everyone now is crying out “Beijing, baby, Beijing”. Maybe those giving the go-ahead felt that the average Irish brain is only capable of absorbing the dimensions of this vast new retail space by first forcing out the information about how much unused commercial property NAMA still holds on its books and which it is unlikely to sell.

Of course, through the worst global depression since the 1930s the fate of the Chinese economy and that of the Irish one (and the economic policies of the respective governments pursued) couldn’t be further apart. But there is one aspect of economic policy which is quite similar. It is the incredibly generous treatment they give to successful foreign multinationals like Apple.

There could be a number of reasons for the similarity of this behaviour, but I would like to highlight one possible historical link. The word ‘comprador‘ comes from a Portuguese word meaning ‘buyer’, but it refers to what Webster’s dictionary defines as “a Chinese agent engaged by a foreign establishment in China to have charge of its Chinese employees and to act as an intermediary in business affairs”.

The fact that the Irish “comprador” class has controlled Irish economic policy to the wider detriment of the republic since the foundation of the state is now well established thanks to Conor McCabe in Sins of the Father. The Chinese government’s willingness to protect the interests of foreign investors at the expense of the native economy is perhaps counter-intuitive, given the incredible levels of growth the country has been experiencing since the late 80s, but evidence is emerging that this is in fact the case.

All about Apple

It seems no one can touch Apple. They are the exemplary company. They sell the most sought after electronics gadgets, their brand is associated with innovation and style; customer loyalty is second to none and they are the most successful non-financial company in the world. It is a company that almost every other business feels they should emulate and their business model is now considered the standard that other businesses should set for themselves. Such was the close association of the success of this model with Steve Jobs himself that when he died it was felt that finally Apple had given way to the inevitability of entropy. With the winking out of such a soul, so too would the company which had reached such heights begin its slow decline.

Perhaps, but not so far. Bloomberg reported last Wednesday that profit at Apple Inc. almost doubled in their last quarter, with sales climbing 59% to $39.2 billion. The company is also the richest “cash king” of the non-financial corporate sector. In March a Moody analysis of US non-financial corporate cash piles showed that Apple is by far the biggest hoarder of corporate cash.

“Apple alone represents $64 billion or 36% of the total $179 billion increase in corporate cash since 2009. And in 2011, overall corporate cash would have actually declined by $6 billion had it not been for Apple’s $46 billion increase…”

Now that cash pile amounts to “$110.2 billion in cash and investments on its balance sheet” according to Bloomsberg last week.

And Apple’s phenomenal news has reached these shores too, as it announced last week that 500 new jobs will be created in its Cork operation, which is now acting as its Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) sales hub.

Apple’s products are said to have a ‘brand halo‘ and are considered by the many millions drawn to the sleekly designed and easy to use gadgets as the epitome of cool. Indeed, Apple is sensitive to protecting its cachet with purchasers. The recent reports of terrible working conditions at Foxconn, the Taiwanese manufacturer of many of the components, which bases its factories in China, has moved Apple to not only commission the Fair Labor Association (FLA) to report on conditions, but it is also the first tech company to join the association.

The FLA is interesting in itself. As the New York Times informs us:

“The association was founded in 1999, by universities and nonprofit groups, along with Nike, Liz Claiborne and several other American apparel companies that said they were eager to eliminate workplace abuses; at that time, anti-sweatshop groups were pummeling American apparel companies for abuses in overseas factories they used.

Since its founding, the association has inspected more than 1,300 factories in Asia and Latin America, uncovering myriad violations. But despite these successes, many labor advocates say its efforts have barely made a dent in improving working conditions.”

The FLA doggedly declares its independence in the face of such reports, stating that

“Companies have no say in which factories are audited, and agree to full disclosure of the findings.”

Even so, a 2009 tax filing shows that “its revenue was $4.8 million, $3.5 million of which came from dues from member companies and organizations.”

Jeff Ballinger, director of Press for Change, a labour rights group in the US, considers the FLA to be ‘largely a figleaf’, telling the NYT:

“There’s all this rhetoric from corporate social responsibility people and the big companies that they want to improve labour standards, but all the pressure seems to be going the other direction - they’re trying to force prices down.”

But Apple products are not cheap when compared with similar products, many of which contain the same generic components manufactured by Foxconn.

Profit maximisation behaviour

Due to the globalised nature of capitalism now, we are told, most manufacturing is moving to China as labour costs are too high in places where Apple products used to be made (including Cork). If companies are to remain profitable in a highly competitive marketplace they have to go where labour is cheapest.

But while this is considered be a loss to the countries that used to have these jobs, the logic continues, it is a boost to both the companies in China where the manufacturing is subcontracted to, allowing them to grow - and ultimately the Chinese economy benefits. However, a new study from the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change (CRESC) of the Apple Business Model shows that the reason for this move is not to gain competitive advantage but for Apple to maximise its profits; and that outsourced companies are not particularly benefitting from the relationship - following from that, neither is the Chinese economy.

Writing about the study in the Guardian last week, Aditya Chakrabortty cites an Asian Development Bank 2010 working paper which looked specifically at the manufacturing of the iPhone 3G in China. The paper suggests that there are two possible reasons why Apple would use China as the assembly center for iPhones:

“The first could be because of fierce competition in the smart phone sector that forces Apple to find a low-cost assembly location. In such a situation, Apple would be faced with either a profit margin that is too low to be sustainable, or price-setting such that it would not be able to find buyers. The other possible reason would simply be the profit maximization behavior of Apple and the demands of Apple’s shareholders.”

Having completed the study the authors of the paper conclude “that it is the profit maximization behavior of Apple rather than competition that pushes Apple to have all iPhones assembled in the People’s Republic of China” (my emphasis).

It’s an opinion matched by the CRESC research, which looks at the relationship between Foxconn and Apple. CRESC examines this relationship in the context of a similar rise in the fortunes of Japanese and Korean manufacturing firms in the 70s and 80s which had a similar competitive advantage to Foxconn as they were based in a low wage economy selling their cars and electronic goods for good prices in the West.

It is the profit maximisation behaviour of Apple that determines the cost structure and it is Foxconn that has to tailor its business to meet those needs. These needs include its PR problem with conditions at Foxconn, as revealed officially in the FLA report. Chakrabortty provides a useful summary explaining how the relationship works:

“Foxconn, which makes those iPhones, has to work to an incredibly tough contract with Apple that forces it to keep all costs to a minimum. This surely helps account for why Foxconn, whose client list is almost a Who’s Who of the smartphone sector, has had repeated troubles with its workforce, including at least 18 suicide attempts by workers in 2010 alone. After that, and the terrible publicity that followed, Apple put pressure on its subcontractor to raise workers’ pay and improve conditions. But it didn’t take the most obvious route of doing so, which would be: pay more to Foxconn, and direct it to use that surplus to increase wages.”

Instead Foxconn moved production “inland to provinces like Anhui, Jianxi and Hubei where labour costs are even cheaper (FT, 18 November 2010) or offshore to Indonesia and Vietnam where wages are now lower than at some Chinese sites (FT, 10 February 2011)” (p19).

The CRESC report looks at Foxconn International Holdings’ (FIH) financial reports and accounts and uses a quote from the Chairman of FIH’s statement in the most recent FIH annual report, which, it says, “reads as though this was a mature US or Japanese company under pressure to restructure”:

“Several factors challenged our business in 2010 and disappointing financial results have created a deep sense of urgency for the management team and across the company. We have taken drastic measures to better cope with market dynamics and barring any extraordinary event, I believe we are well positioned to return to profitability in 2011.″

(FIH Annual Report, Chairman’s Statement, p.4)

It must be noted that FIH, which financially is based in the Caymen Islands, is listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange and which owns Foxconn, is the trading name of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. Ltd., the world’s largest electronic component manufacturer. Hon Hai employs a million people. The point however, is about the relationship between it and Apple.

“By the measure of size, new corporate giants like FIH should be well positioned since the parent, Hon Hai is the world’s largest electronic component manufacturer and FIH its subsidiary is the world’s largest contract handset assembler, competing against a maximum of five other companies that can combine both scale and price that FIH offer. But this is a dependent relationship, with their status as corporate giants secondary to their ability to bargain with Western businesses largely dictating price and insisting that the burden of adjustment in the fast moving competition between final products are borne downstream” (emphasis mine)(p17).

Of course this dependency is something that the Chinese government, local and centrally, do not appear to be too exericised about. They too, the authors write, must “also take some of the blame because it has never sought a balanced relation between the domestic and export markets”.

The CRESC compares this relationship to the situation in Japan in the 1970s and 80s, which developed manufacturing towards two goals,

“which would provide a secure and steady revenue base for their producers: provide low-cost alternative manufactures to Western export markets, and to produce low-cost goods to stimulate local demand in the domestic market (Williams et al., 1995). China, by comparison, has concentrated on the one goal of developing exports” (p19).

The decision of the Chinese government to maintain this dependency when other successful examples of economic development which move beyond it exist, provides an illustration of the basis of their national economic plan.

Looking to Apple’s own business model CRESC then argues that Apple’s ultimate aim is to “generate huge profits from tactical innovation in the volume sale of ‘must have’ devices (iPod, iPhone, iPad) assembled from generic components so that Apple makes hefty margins - including a 72% gross margin on the iPhone 4 or $452 on a selling price of $630 (p.20).” This business model is fragile they say,

“because it is always dependent on the next hit product, and this fragility is countered in several ways by a multi-dimensional business model which involves minimising cost and maximising revenue streams from hardware devices and software products.”

This profit maximisation has led to an enormous mountain of cash. Apple Inc. rose from “287th to 1st place in the S&P500 ranking over a 10-year period between 2001 and 2011, overtaking the market capitalization of oil and gas conglomerate Exxon Mobil in August 2011″. Based on data from the beginning of April, “Apple’s market capitalization of $588.95bn is around 122% more than that of its nearest tech sector rival Microsoft at $265.15bn” (p21).

CRESC then argue that Apple are so successful that they could keep production in the US, reducing these margins and still remain by far the most profitable tech company on the planet. Labour costs in China are $7.10 for each phone, which accounts for about eight hours of assembly. But CRESC, using the average wage in the US electronics industry of $21 per hour, calculate that the total production cost of a US-based operation would increase the cost of each phone to $337.01. This would leave Apple with a gross margin of 46.5% on each iPhone. More expensive for Apple perhaps, but this smaller margin “would probably still make it the most profitable phone in the world“.

However, reducing this margin is not what Apple is about. However, you have to ask, what is Apple doing with all these profits that it’s maximising? In short it’s sitting on it. On 19 March, as the Moody note indicated might happen, Apple CEO Tom Cook announced plans to initiate a dividend and share repurchase program in the second half of the year.

Of course, one of the biggest beneficiaries of this repurchase program are those who have a portion of their salary in share-options, the lion’s share of which rests of with the senior executives. To quote Chakrabortty again:

“Among other people who benefited from this arrangement was Cook himself, who was awarded $376.3m in Apple stock when he took over last year. That pile of shares is now valued at around $634m. The people who win from the made-in-China model are big investors and top executives.”

That tax ain’t coming back

But there is another aspect to this that is not mentioned in the CRESC report, and perhaps provides another reason why Apple are happy to say, as it is reported Steve Jobs said to Barack Obama, that “those jobs ain’t coming back” to the US: the share repurchase scheme only applies to a portion of the cash pile that Apple has amassed. As mentioned on Irish Left Review, and highlighted by Citizens for Tax Justice, the repurchase scheme will only apply to Apple’s US cash:

“CFO Peter Oppenheimer went out of his way to point out that the dividends would be paid entirely from Apple’s U.S. cash, which means the $54 billion Apple has stashed in foreign countries will stay there. Oppenheimer explained that ‘repatriating cash from overseas would result in significant tax consequences under U.S. law.’

He’s not kidding! CTJ has estimated that Apple has paid a tax rate of just over three percent on this stash of ‘foreign’ earnings, a clear indicator that much of this cash is likely parked in offshore tax havens and has never been taxed by any government. If Apple brought this cash back to the U.S., they’d likely pay something close to the 35 percent corporate tax rate that the law prescribes. The resulting $17 billion tax payment would be more than double the $8.3 billion in federal taxes that Apple has paid on its $83 billion in worldwide profits - over the last 11 years.”

The tax justice NGO also goes on to mention that Apple has been lobbying hard as part of the Win America Coalition “for a repatriation holiday (a.k.a. tax amnesty) which would allow them to bring back those unrepatriated profits at a super-low tax rate”.

Now I realise that Apple is so much in the news these days that it’s difficult to keep up with all the stories that the tech giant is able to generate, but there was one that I was surprised bypassed the Irish media entirely. Over in the UK there has been a series of news stories rippling around the fact that most of the successful internet and tech companies are doing a bang up job of paying absolutely no corporation tax in the UK, despite generating a significant volume of sales in the territory.

Amazon UK was perhaps the most significant. As the Guardian enblazoned in its headline on 4 April: Amazon: £7bn sales, no UK corporation tax.

“The UK operation avoids tax as the ownership of the main Amazon.co.uk business was transferred to a Luxembourg company in 2006.”

How this works is explained well here.

“The corporation tax rates in Luxembourg and the UK are similar, but the Luxembourg authorities have a different view of costs that can be offset against income, which reduces taxable profit. So Amazon EU Sarl’s €7.5bn of income in 2010 was almost entirely offset by €7.4bn of charges, enabling it to disclose a tax charge of just €5.5m.”

Google Inc’s use of the ‘double irish’ and ‘dutch sandwich’ are well know thanks to Bloomberg reporter Jesse Drucker, yet what is less well known is that because of this 96% of Google’s global earnings now pass through Ireland, based on the most recent set of accounts. But the revelation about Amazon revealed that the UK’s Inland Revenue was also investigating other very profitable but low tax companies which used transfer pricing to reduce their UK tax bill. Envying the Guardian’s publication of the details around Amazon the Daily Telegraph revealed that Apple was under investigation from inland revenue for the fact that

“…the Californian group paid just £10.3m in corporation tax in the year to September 25, 2010, according to reports. Apple’s British turnover is thought to account for a tenth of worldwide sales, which hit $100bn (£63bn) in its last financial year. The US giant avoids paying higher taxes by using foreign subsidiaries, such as in Ireland and the British Virgin Islands.”

Apple in Ireland

Apple set up in Ireland in December 1980, the month the company went public, offering $4.6 million shares at $22 each. Coincidentally a few months later Ireland adopted a 10% corporation tax rate for manufacturing, which led to an influx of FDI into Ireland. It is significant that despite this influx Ireland remained in recession. In the Telesis Report, published to much controversy in 1981, 80% of the foreign companies that set up in Ireland said they did so to avail of the generous tax reliefs available. In 2006 however, Apple Computer Inc Ltd. in Cork converted itself into an unlimited company, following the same route as Microsoft’s Round Island One Ltd. in the same year. The unlimited status means that it is allowed to keep its financial results a secret. Microsoft’s manoeuvre was perhaps motivated by a Wall Street Journal article in 2005, which stated:

“The four-year-old subsidiary, Round Island One Ltd., has a thin roster of employees but controls more than $16bn in Microsoft assets. Virtually unknown in Ireland, on paper it has quickly become one of the country’s biggest companies, with gross profits of nearly $9bn in 2004.

The citizens of other nations where Microsoft sells its products are less fortunate. Round Island One provides a structure for Microsoft to radically reduce its corporate taxes in much of Europe, and similarly shields billions of dollars from U.S. taxation.

Giant U.S. companies whose products are heavily based on their innovations, such as technology and pharmaceutical firms, increasingly are setting up units in Ireland that route intellectual property and its financial fruits to the low-tax haven — at the expense of the U.S. Treasury.”

Apple’s Irish operation is reported to employ between 2,800 and 3,000 staff at the moment and is the operational headquarters for EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa). Singapore, with a corporation tax rate of 17%, also hosts Apple’s Southeast Asian regional subsidiary. The relevance of this is that Apple Ireland is a considerable part of the hub of global sales. As Michael Hennigan of Finfacts points out:

“The importance of Apple’s Cork operation covering the EMEA and part of Asia is illustrated by the fact that in 2003 when Apple Inc reported an operating loss of $1m, Apple Cork reported an operating profit of $224m. In 2004, Apple Inc reported global operating income of $326m; Apple Cork reported an operating profit of $393m.

Cork revenues in 2004 were $3.3bn compared with Apple’s global revenues of $8.3bn. By fiscal year ended September 24, 2011, Apple’s global revenues had jumped to $108.2bn.

Even though access to the current accounts of Apple Cork’s operation are not available, it’s reasonable to assume that revenues for services for a significant operation of the world’s most valuable listed company are now in the double billion digits.”

(It is perhaps more than likely, given the surge of sales of Apple products in China, that the products made there never actually leave the country. But while the actual product doesn’t leave the sale does - while they could be booked in the US, its more likely to be either Singapore or Cork. See comment two from Jianmang Li, which mentions that Apple ‘export’ to China too).

However, while the 12.5% rate is no doubt important to Apple, what is perhaps more important from a tax perspective is Ireland’s complete lack of interest in investigating Apple’s tax affairs and its manipulation of profit, as the UK tax authorities are doing. What Ireland is offering a company like Apple is not the 12.5% rate, because only a tiny portion of their incredibly large global earnings that pass through Ireland are ever subject to that rate. What Ireland is really providing is the means by which very profitable corporations can avoid tax in other jurisdictions. That they are avoiding it in Ireland doesn’t seem to matter. However, the negative image that the use of tax havens has gained in the last decade is Ireland’s trump card. It allows companies to avoid tax, while also appearing to be based in a legitimate, internationally tax compliant country. Essential to this is Ireland’s membership of the European Union; the fact that we are subject to EU directives, being on the OECD ‘whitelist’ even though the IFSC is described officially as an “offshore tax haven”; being in the Euro and having an internationally recognized “well regulated” stock exchange. Without these the figleaf of the 12.5% would be useless.

So unlike well-known off-shore tax havens, Ireland does have regulations. Yet it is clear that Ireland doesn’t wish to impose those regulations in a strict way. As Richard Murphy of Tax Research UK put it when I interviewed him in February:

“You can’t sell your country as a place in which to invest on the basis of tax and then have an aggressive tax authority. It just isn’t possible. If you have an aggressive tax authority in that situation, you are going to end up with a situation where you go to all this effort to get a company into Ireland to actually locate and create jobs and so on and then discover you have completely alienated it by investigating its tax affairs.”

This ‘soft touch’ is reproduced in legislation.

“So although it has a comprehensive network of double tax treaties, legislation to deal with transfer pricing has only very recently arrived in Ireland and is still quite frankly not considered as an issue. Consequently, it is very easy to move money in and out of Ireland via transfer pricing abuse without any questions being asked. It hasn’t got a thin capitalisation rule, which allows you to load your debt into Ireland and nobody is going to ask any questions. You can pay your royalties, in particular, and your copyright fees out of Ireland, which is a major exercise going on now with regards to companies like Google and, well, Facebook to come. Microsoft already. So you can use these fees as a cost for intellectual property. It’s actually incredibly easy and these are not subject to challenge. What we are seeing is a situation where companies are able to bill from Ireland, and they can enjoy the benefits from billing in this way without having any risk arising from having tax payment to Ireland and without any real challenge to this because it’s seen as a compliant state. The money, therefore, flows straight out of Ireland again because of its lax regime- one, a lax regime simply by not asking questions and two, a lax regime because we’ve got the situation where, by not choosing, and I think it’s absolutely right to say ‘not choosing’, to put in place regulation to stop the money flowing out. It is deliberately viewing itself as the conduit, in other words.”

The transfer pricing mechanism is also explained very clearly in the Irish segment of the Tax Justice Network’s report on Secrecy Jurisdictions, citing the example of Google, which reportedly uses Bermuda as an offshore location to reduce its global tax rate to 2.7%.

In the case of Apple, however, and as reported in the Telegraph, it is the British Virgin Islands. According to Citizens for Tax Justice, Apple has paid a tax rate of just over 3% on its very substantial “foreign” earnings.

Ireland’s benefit from Apple’s business, we are told is corporation tax and jobs. Indeed, Apple recently announced that it was to looking to increase this 500. Good news for us, even if it is at the expense of the tax base of other countries, right?

First of all, with the second highest unemployment rate in what the IMF refers to as advanced European economies, at 14.4%, we shouldn’t sniff at any job creation. But we must also discuss the quality of the jobs being created, and whether they will make any impact on the level of unemployment and therefore on the real Irish economy. As mentioned, Apple in Cork is the EMEA hub for Apple global and all of the 500 jobs relate to online and regional European sales - that is, they are call centre jobs employing people from other European countries so that customers calling from their own country will talk with a sales rep who can speak their own language.

More importantly we have to look at what the process of attracting FDI based on tax incentives does for the Irish economy and job creation. Because, as we know from the regular distinction made between Ireland’s GNP and GDP, most the ‘exports’ attributed to this business are greatly exaggerated. While the productivity per employees in mainly US companies like Apple has ballooned disproportionately, the real value of exports has remained relative static

As Michael Hennigan’s analysis shows, Irish exports of goods and services went from €98bn in 2000 to €164bn in 2011, according to Ireland’s Central Statistics Office. Foreign-owned firms, mainly American, are responsible for about 90% of Irish tradeable exports, yet “the real value of goods exports has been almost static since 2000″.

But despite the announcements made by Apple and Cisco recently it is the financial sector which has seen the main job growth.

“Foreign firm employment in financial services increased from 6,300 in 2000 to 15,100 in 2010, according to Forfás, while financial services exports rose from €3.5bn in 2000 to €13.3bn in real terms in 2010.”

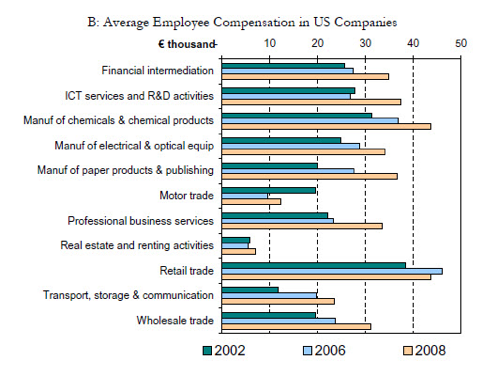

And even then, these new jobs are usually call-centre operatives and fund administrators. A 2010 report The Economic and Fiscal Contribution of US Investment, read to the IIIS by Keith Walsh of the Revenue Commissioners, provides some interesting data on income tax revenue from employment created by US firms in Ireland. According to table 11 B on page 23, income earned by those employed in the retail trade was a good deal higher than those employed in financial services:

Employment levels in foreign firms outside of the financial sector in the last 10 years, however, have remained relatively flat:

“Forfás says that excluding financial services, the number of export services jobs in foreign firms in 2000 was 41,500 and 44,000 in 2010.”

This confirms what I have already pointed out - there has been virtually no change in foreign-based industrial employment between 1983 and 2006 and in 2007 the total for direct employment by foreign direct investment in Ireland was 152,267, or 7.25% of the workforce.

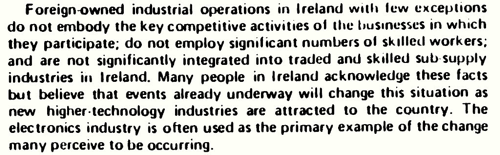

This lack of real economic benefit to the Irish economy from foreign direct investment is not unexpected. After all, it was outlined clearly if controversially in a report published around the time that Apple was establishing itself in Ireland. The following is taken from the Telesis report published in 1981:

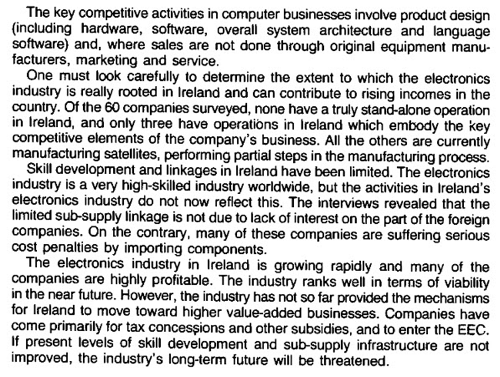

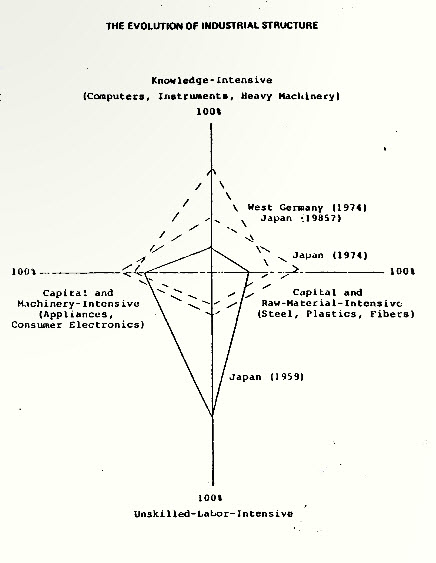

One can see that the hope expressed was that the success of the electronics industry, which would have included Apple at the time, would bring about a restructuring of Irish industry similar to the Japanese model that Telesis highlighted as the means for countries with an initial disadvantage to develop a strong economic base.

However, the problem with Ireland’s ability to attract this investment was already apparent.

The problem was not in attracting this investment, it was about using this investment to move Irish industry towards the development of higher value-added Irish businesses - that is, export led growth is useless without it feeding back into the domestic economy. It is striking that Ireland repeatedly failed to do this. Ireland had managed to attract 80% of the foreign direct investment which Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Belgium were also competing for. Given this success there was never an attempt to reduce the incentives available in order to get a better deal and to move the saving from unnecessary incentives to the indigenous sector. For the report Telesis interviewed 100 multinationals which had either located part of their operations in Ireland or had considered it, as well as discussing it with officials from other development agencies. “The distinct impression left by these interviews,” the authors comment, “is that Ireland may be offering more than is necessary, in many cases, to attract foreign-owned firms to the country” (p29).

Ultimately the recommendation of Telesis was that Irish industrial policy should shift its emphasis from spending too much attracting foreign-direct investment - which is only interested in using Ireland as a tax shelter within the European market and offers only low-value employment with very little linkages to the Irish economy - and instead use its resources to ‘pick winners’ in the indigenous sector and nurture them until they become strong, internationally traded companies in their own right.

Given that Ireland still doesn’t have any companies that have gained such a stature (after decades of infrastructural investment from the EU as well as a significant portion of the top S&P 500 companies locating in Ireland) we can see that these recommendations were never implemented.

In a report read to the IIIS as a response to the Telesis report in 1981, the head of the IDA at the time, Padraic White, stated the following:

“(iii) Foreign Industry: Given the magnitude of the employment needs for the next decade, we cannot afford to ignore the potential for output growth in foreign industries. The recent debates on industry have revealed much ambiguity and questioning of the role of foreign industry. There has been considerable divergence between the IDA and commentators on the pace and extent that key business functions such as research, marketing and purchasing can be located in Ireland. There is also considerable divergence over the incentive cost which has to be paid to attract such investment. The environment for attracting foreign industry is more competitive now than ever with most European countries entering the arena in a highly professional manner. If Ireland is to maintain its hitherto strong position in the market for foreign investment, the equivocation over the role and desirability of foreign investment needs to be quickly brought to a close.

(iv) Identification and Development of Special Niches: In aiming to achieve high levels of output growth Ireland could identify and develop its own specialised opportunities for growth. Many attractive opportunities are beyond our aspirations in both financial and other terms. Ireland simply cannot afford the broad based technical approach of many developed countries. IDA possesses a unique combination of sectoral experience and commercial knowledge which will enable it to identify and develop suitable niches on behalf of industry: specialised computer software is an example.

(Just to note, it is rather odd that the emphasis is on “output growth in foreign industries”, rather than finding a way to build more indigenous links to the companies that were in the country already. As we have seen over the decades, output from multinationals in Ireland has exploded and as a result productivity per employee is staggeringly large when compared to export-orientated Irish companies. This productivity, of course, is related to MNC profit laundering.)

One of the ways of developing that niche in specialised computer software was to make use of the changing tax environment in the US. This change had come about because of the rapid increase of US companies using tax havens to hide corporate profits. To get around this problem the US government brought in Tax Deferral - the ability to defer the payment of tax by US multinational on profits earned outside of the USA. The consequence of this change means that profits that US MNCs earn in countries like Ireland are never repatriated. The deferral is an interest free loan, and there is never any pressure to bring those profits back. The significance of this for a company like Apple means that its ability to plough its cash surplus into share buybacks, as they did recently, is limited to only that portion of their profits that are booked in the US. No wonder they’re looking for a repatriation holiday!

We know that Irish officials considered the Tax Deferral measure to be very important for Irish industrial policy and we know this because Padraic White explained it to George Bush’s Treasury Secretary John W. Snow when the latter was visiting Ireland in 2004. The purpose of the visit was to talk to those the US Ambassador considered the most responsible for the success of the ‘Celtic Tiger’. What was discussed at the meeting was revealed in the Wikileaks-released US Diplomatic cables (published in 2010), and shows how it was considered that Ireland’s industrial policy was entirely dependent on the US Tax Deferral mechanism.

“8. (C) The U.S. policy of tax deferral for foreign subsidiaries of American firms, combined with Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate, underpinned the large influx of U.S. investment to Ireland during the Celtic Tiger period, observed Padraic White, former CEO of Ireland’s Industrial Development Authority (IDA). White recounted his numerous trips to the U.S. House of Representatives, Ways and Means Committee to defend tax deferral, and he argued that Senator Kerry’s plan to reverse tax deferral would have “killed Ireland,” had he been elected.”

Resistance to change

The publication of the Telesis report should have been an occasion to take stock of what had not worked in Irish industrial policy up to that point. It should have been an opportunity to move beyond the ‘dependency’ of relying on a trickle of returns from well-established and powerful international companies while at the same time gifting the benefit of that business to small, yet powerful groups within the Irish ‘buyer’ class.

Reconstructing the Irish economy upon the lines suggested by Telesis would have initiated the beginning of significant social and economic change in Ireland. Every effort was made to avoid this happening.

It is significant that both Telesis and the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change report point towards the Japanese model of industrial development as a way to build a strong genuinely Irish export sector while also developing the domestic economy.

The weakness of Ireland’s industrial policy is very relevant to the current problems in the Irish economy. The measures being put in place now, by the present government, while high on rhetoric, compound and extend the poor practices that Telesis highlighted, and given the massive austerity imposed since 2008 illustrate that there is absolutely no interest in doing anything for the domestic Irish economy. It is clear, with all the talk of the need for a second bailout and whether or not the Fiscal Compact Treaty referendum would make this available or not, that rather than trying to do everything to avoid the need for it the Irish government is doing everything to ensure that Ireland will require a second program. And that would result in even more conditionality and more opportunity for those looking for short-term gains to strip the country of econmic and social goods.

{jathumbnailoff}