Making public sector reform work for people and the economy

The government can take a different approach to public services, one based on growth, efficiency and targeted investment to achieve better outcomes. By Michael Taft.

In previous posts (here and here) I showed that Irish public services were already grossly underfunded by EU norms and that, using ESRI data, cutting public sector employment will have only a trivial impact on the fiscal deficit. In this, the last of three posts on public services, I will sketch out an alternative fiscal approach to public services.

It should be borne in mind that past surveys have found Irish public services relatively efficient compared to EU norms. While measuring public sector productivity is a difficult exercise and the methodology is still being developed:

- The joint Netherlands-OECD Study into Public Sector Performance found Irish public sector performance to be above average, besting even the German and UK public sectors – measuring quality of administration, allocation of services, distribution of welfare and economic stabilisation.

- The European Central Bank study of public sector performance describes the Irish public sector as one of ‘the most efficient’ along with Australia, Japan, Switzerland, the US and Luxembourg.

While these studies date from the early 2000s, and are certainly not the last word, there is clear evidence that the Irish public sector has a credible track record. Of course, this goes against the manufactured consensus that our public sector is bloated and inefficient, but it wouldn’t be the first time that unsubstantiated assertions meet empirical analysis.

1. From Cuts to Overall Freeze

The policy of reducing public sector employment should be abandoned and, instead, should be replaced by a ‘freeze’ at the current levels of public sector numbers. This would introduce greater flexibility whereby redeployment and reformed work-place practices take place alongside continual recruitment to maintain overall numbers, rather than allowing natural wastage and redundancy initiatives to undermine service quality.

The impact on the deficit would be minimal while the benefits to the economy would be considerable.

- The economy would increase by €1.3 billion

- Consumer spending would increase by over €1.1 billion

- Employment would rise by more than 25,000 (in excess of the public sector jobs as higher growth and consumer spending increases the number of private sector jobs)

The deficit would only rise, on a static basis, from 2.8% to 3.1% by 2015. I say ‘static’ because it assumes there are no changes to other fiscal policies or we fail to use public sector reform as an instrument of growth. But see below how we can turn static into dynamic.

2 A New Policy of Public Service Expansion

It’s not enough to reform current practices; we must have a policy of expanding public services as a form of investment and growth within the constraints of maintaining overall numbers.

For instance, let’s assume that natural wastage will free up 4,500 jobs per year (assuming a conservative wastage at 1.5%). This will create over 20,000 vacancies over the next five years. Under the current recruitment moratorium there are some categories exempted (e.g. teachers, social workers, etc.).

If we get rid of the moratorium we could find capacity for greater employment growth without actually increasing the overall cost to the state. So why don’t we start expanding public services.

We could start rolling out early childhood education – one of the best investments we can make into future growth and current social equity. We could start introducing childcare services at below-market costs to parents (for instance, in Sweden childcare charges range from $65 to $119 per month). These low fees would reduce household costs which in turn would free up more money to be spent in private businesses – thus increasing demand and growth.

Or we could start expanding primary health care trusts in anticipation of free GP care and, hopefully, prescription medicine. This would save money down the line as demand is shifted from expensive, capital-intensive hospital care to more labour-intensive but less costly primary health care.

And the great thing is that we are merely rearranging resources – there is no extra cost to the Exchequer. But all the time we are maintaining tax revenue, employment and demand in the economy.

All this requires a vision of public service expansion which can begin within an overall freeze in public sector numbers but can eventually start expanding once recovery has set in – an expansion which itself can contribute even more to more growth and cost savings.

3. Whatever You Do, Measure It

It is absolutely critical that we move away from crude accountancy methods to more sophisticated models of measuring economic and fiscal impact. Let’s take two examples from An Bord Snip:

- Reducing GMS payments to GPs to ‘save’ €370 million: I’m all for this; if higher paid public sector employees have to cough up over 12% in pay cuts, there’s no reason why GPs shouldn’t face the same. Such cuts are likely to have minimal impact on demand, though some GPs might reduce their own ‘inputs’ (usually labour) to make up for the loss. But would this ‘save’ €370 million? No. Being taken off income, it would save 50% less – as more than half of the amount would have been returned to the Exchequer in tax. Identify the actual savings, after tax and economic impact: it’s still a good idea but the headline €370 million is highly misleading.

- Reducing medicine procurement costs: this proposal is likely to save the headline reduction of €30 million since the impact would be on drug companies which can more easily absorb the costs.

Each measure that is taken to ‘save’ money should be measured using a model that actually identifies the impact on the economy and the Exchequer. We have seen that cutting public sector employment makes almost no savings. We might find that what is called ‘non-pay’ savings actually reduce contracts to the Irish private sector, which means loss of income, employment and tax revenue. These are not savings, these are actually costs.

Public sector reform is serious business. We need a serious measurement.

4. Create Efficient Balance Sheet Measures

There are three sides to the national balance sheet – tax revenue, current spending and investment. Unfortunately, the debate ignores this. Many commentators claim that investment is a cost, rather than it being a down-payment on future income – a contributor to growth, tax revenue and spending reduction (namely, unemployment costs). That being said, let’s work the tax/current spending axis.

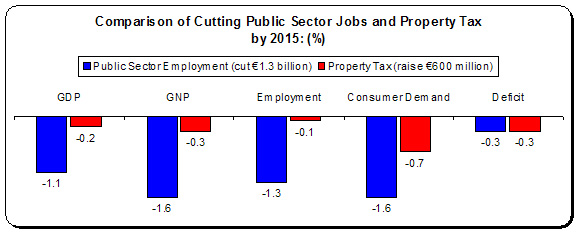

Using the ESRI data let’s compare two fiscal measures.

- The Government’s programme of cutting 22,500 jobs which will lead to an approximate reduction of €1.3 billion in current expenditure

- The introduction of a property tax designed to raise €600 million (or less than half the spending cut).

As seen before, cutting public sector jobs is highly damaging to the economy. The property tax, however, is less damaging – substantially so.

And the kicker is that both achieve the same level of deficit reduction. Why is this so? Because property tax does not cut GDP, employment and consumer demand by anything approaching cutting public sector jobs. But why are we surprised? Taxing capital is always likely to be less damaging than cutting employment of people.

* * *

By maintaining current employment and spending levels in public services, we have the opportunity to expand the quality and range of public services. And the extent to which real ‘savings’ can be made through public sector reform, this can add to growth.

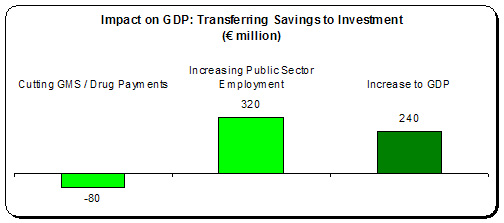

For instance, if we can actually save €200 million from reducing GMS and prescription medicine costs (about 50% of the headline rate once the loss of tax revenue is taken into account), we employ thousands of teachers and assistants in universal early childhood education providing thousands of places. Why would this add to growth?

- Because the ‘cuts’ would have minimal deflationary impact

- Because the extra jobs would increase demand, raise tax revenue and reduce unemployment costs

Here is a back of the envelope calculation, assuming that the overall cuts to GMS and prescription medicine costs will result in a 20 % loss to GDP.

Taking the actual savings and reinvesting them into expanding public services, we find an increase in GDP growth. And when you consider that this has been done with no overall increase in expenditure, but with an increase in tax revenue from employing more people, we will find the fiscal deficit being lowered as well. This is win-win-win (by the way, the positive impact on GDP would be considerably more as education investment has very high impact in the medium term; the above only measures the short-term effect of increasing employment).

This is the new approach to public services based on growth, efficiency and targeted investment to achieve greater outcomes that can be measured in equity and economy. The is the new approach building on the strengths that international agencies have discovered in the public sector and working through the weaknesses in a forensic manner. This is the new dynamic approach that can help us get out of the EU-IMF bailout trap.

There is only one question left: what are we waiting for?

Image top: Ben (Falcifer).

{jathumbnailoff}