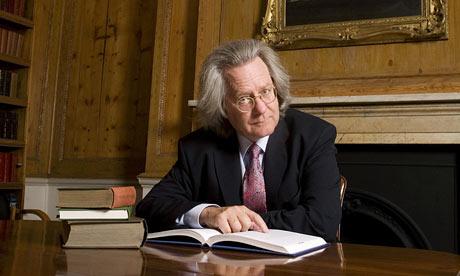

Looking back: A.C Grayling's Among the Dead Cities

Taking a look back at A.C. Grayling's Among The Dead Cities: Is The Targeting of Civilians in War Ever Justified? By Joseph Mahon of NUI Galway.

In this well received book, the philosopher A.C. Grayling sets out to answer two questions: During the Second World War, was the blanket bombing of Dresden, Hamburg, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki a crime against humanity? Is such 'area bombing' ever justified? Grayling's answer to the first question is: Yes, these acts of war were a crime against humanity. His answer to question two is: No, area bombing is never justified. For the most part, Grayling treats these two questions as if they were logically related, in the sense that he reasons repeatedly that a Yes answer to the first question entails a No answer to the second. But such reasoning is unsafe: from the fact that the above acts of war were a crime against humanity, it does not follow that area bombing as such is a grave moral wrong. It may be wrong always, or even of its very nature, but that is something which has to be separately demonstrated.

In keeping with the distinctions employed in just war theory, Grayling argues both that the war against Germany and Japan was a just war, but that not all the means used to wage that war were themselves just. He is also anxious to assure his readers that on the scale of wrongs, there was no comprison between Allied wrongs and Axis wrongs. As he unequivocally puts it himself: "it is unquestionably true that if Allied bombing in the Second World War was in whole or in part morally wrong, it is nowhere near equivalent in scale of moral atrocity to the Holocaust of European Jewry, or the death and destruction all over the world for which Nazi and Japanese aggression were collectively responsible: a total of some twenty-five million dead, according to responsible estimates. Allied bombing in which German and Japanese civilian populations were deliberately targeted claimed the lives of about 800,000 civilian women, children and men. The bombings of the aggressor axis states was aimed at weakening their ability and will to make war; the murder of six million Jews was an act of racist genocide. There are very big differences here."

In chapter 6, Grayling articulates what he calls "The Case Against the Bombing." This is a series of arguments designed to show "that the Allied practice of area bombing in the Second World War was wrong." "By 'wrong' here I mean a moral wrong," he writes, "a violation of humanitarian attitudes and civilised standards of treatment of human beings." His argument is not that the Allies did not have just reasons for going to war, for it is readily conceded that their going to war was amply justified on just war theory; rather the argument is "whether the Allies, in carrying out area bombing, acted justly once engaged in their just war."

Graylng argues that the Allies did not act justly in their area bombing. They did not act justly for essentially two reasons: [i] a just military action is one which is necessary and proportionate to winning a just war, and the area bombing was neither necessary nor proportionate; [ii] "there are some things that should never be attacked or harmed even if doing so brings about or helps to bring about victory. The main such things are innocent persons and their property." The area bombing during WWII was relentlessly and deliberately aimed at innocent civilians and their property, thus breaking the do-not-harm rule.

For the most part, Grayling relies on argument [i] here to prove his case. He acknowledges that the presumption against targeting civilians had implicitly been challenged since the mid-nineteenth century, but argues that revisions of the rules of war always assumed "the principle that civilian populations should be treated as non-combatants, even if some of their members were engaged in producing weapons or food for troops, because others of their members, perhaps - and probably - the majority of them, would be innocent in the exact meaning of this term: namely, children, the elderly, the lame and ill, and at least many of the women...Therefore to engage in activities which went deliberately against the principle at stake is a central point for the indictment sheet."

Grayling argues that "Massive bombing of civilian targets by any standard is disproportionate, which is what this indictment in effect charges. Take the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: if these were claimed to be attacks on targets of military value... dropping an atom bomb on them is equivalent to chopping off a man's head to cure his toothache, such is the degree of disproportion involved. The same applies to the firebombing of Tokyo, Operation Gomorrah, the bombing of Berlin, Dresden, and indeed all aspects of the bomber war to which the description 'area bombing' applies."

Neither was area bombing necessary, argues Grayling; this is because of "the fact that there were other ways of aiming to hurt war production that greatly lessened impact on civilians, for example, precision bombing, as with the American endeavour in the European theatre, which in the end - in its attack on oil - proved highly effective. The American oil attack was proportionate and pertinent; it could also legitimately claim to be a necessary part of the effort to defeat Germany. The area bombing of civilian populations was not necessary."

The area bombing of Japan was morally wrong for the same reason: it wasn't necessary to do so in order to win the war in the Pacific, and it therefore inflicted gratuitous death and suffering on very large numbers of civilians. It also inflicted gratuitous death and suffering on later generations by way of genetically transmitted cancers and other such afflictions. This last consideration alone, it seems to me, places the area bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in a unique category of moral turpitude.

So, these acts of area bombing were not morally justified. But suppose that area bombing had been necessary, or in some other global war is necessary to win a just war: would area bombing be justified under those circumstances?

Grayling's answer is No! Area bombing under any circumstance is wrong because "it is against the humanitarian principles that people have been stiving to enunciate as a way of controlling and limiting war."

This last argument seems to me less compelling than the previous two. Consider the following counter-examples. Suppose that superpower A is fighting a just war against superpower B. B drops an atom bomb on one of A's cities, and threatens to obliterate two more of A's cities unless it surrenders within 24 hours, and allows B to occupy and enslave it. Would A be morally forbidden to retaliate in kind against B, particularily if doing so would bring B's military leaders to their senses? Suppose that B doesn't merely want to occupy and enslave A, but to wipe it off the map. Is A not entitled to defend itself by whatever means necessary?

Let me now return to Grayling's theatre of war. According to Lawrence Rees's Auschwitz: The Nazis and the 'Final Solution, the Allies did not even consider intervening to prevent the mass murder of Jews in the death camps, not even when they had unimpeachable evidence of what was taking place. But suppose that dropping an atom bomb on a German city - having first demonstrated its hellish effects on a sparsely populated terrain - would have saved the lives of the remaining millions of Jews, and that nothing else could have saved them, would dropping that bomb have been a crime against humanity? I think that many people would now say: Bomb them to Hell and back!

Joseph Mahon teaches at the School of Humanities, National University of Ireland, Galway.