Living the life of Riley

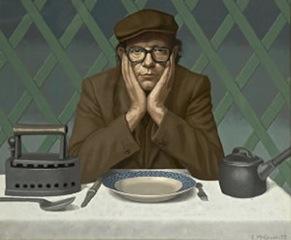

Unavailable for years, Anthony Cronin's The Life of Riley is a first-rate comic novel, about life in the bohemian Irish cultural scene of the 1960's, that also manages to pack a serious punch. Ed O'Hare pays tribute.

For years The Life of Riley has possessed that mystique peculiar to novels with high reputations that are extremely hard to find. First published in 1964 and reprinted only a handful of times, it's a novel remembered for being very funny and very clever. Sadly, it's been out of print so long there won't be many readers under the age of 40 who have enjoyed it for themselves.

New Island books have corrected this by making The Life of Riley one of the inaugural titles in its new Modern Irish Classics series. The wait has been worthwhile.

The Life of Riley is a record of the trials and misadventures of would-be poet Patrick Riley. Put together by a bewildered editor, none other than Anthony Cronin, who explains that he has assembled it from a manuscript found "amongst the late Riley's socks, rags and papers after his death," the picaresque first-person narrative that follows sees Riley slip from one bizarre predicament to another. At the start of the book Riley is, inexplicably, assistant to the Secretary of the Irish Grocers' Association. When not trapped in his office or asleep in The Warrens, an underground space beneath a Georgian house, Riley is to be found in O'Turk's, a seedy public house where "not success, but unsuccess, was looked upon with favour.".

In O'Turks Riley forms part of a "motley throng" of characters who are "not remarkable for honesty, trustworthiness, truth, punctilio, delicacy, scrupulousness, punctuality, dignity, respectability, sobriety, purity, decency, modesty, chastity, continence, cleanliness or shame" - but know how to party. Here Riley learns to practise the hallowed art of pub begging. Riley finds the distractions of O'Turks much more enlivening than work and he hands in his notice, deciding to become a professional beggar.

He loses his income and his respectability, but remains unperturbed. After all, he can get up whenever he likes, has a broom cupboard to live in, has plenty of time to devote to poetry, and to drinking and talking nonsense in O'Turks. But in pursuing his life of beggardom, Riley has made a fatal mistake. He has fallen victim to what he calls the Law of the First Step. This states that for any activity, even beggary, "to be carried to a successful outcome a certain minimum of equipment is necessary, without which no one stands a chance".

As Riley explains, "To get anything you have to have something: a suit of clothes, the price of a first drink in the pub, an ingratiating manner, sufficient food or drink or money to give you confidence to acquire more, what poor Scott called mobility and grace, a penknife perhaps, or even, God help us, a pen and paper and leisure to mature one's schemes." He realises, but too late, that "Sink below the first step and you are undone, permanently and terribly undone."

From here Riley is inexorably propelled towards his doom. He is welcomed into the stately home of a mad English aristocrat who tortures him by playing Mahler. When he returns to Dublin, his broom cupboard has been usurped and he winds up living in a shed at the bottom of somebody's garden. Riley then becomes the unwitting accessory of a conspiracy to launch a new phase of Irish culture when a group of nationalists mistakenly conclude that his beleaguered mind is the point where "the next revolution in Irish thought will come from".

Riley is made editor of a literary magazine called The Trumpet and forced to write articles such as 'Cork Literature: Is it Dead?'

The Trumpet turns out to be a front set up by Riley's fanatical employer, Prunschios, who is using hollowed-out bundles of the magazine to smuggle unknown items out of the country. Prunschios also nurses insane schemes, like paving the streets of Dublin with sods of turf, using messages written on rubbish bins to foment an uprising, and extracting electricity from potatoes. Prunschios sends Riley on a mission to learn more about the mental life of the Irish by going to live in a doss-house in London; this turns out to have even worse ramifications for the wretched poet.

Anyone familiar with Anthony Cronin's poetry, biographies and critical writings knows that he is an outstanding master of language. As an astute reviewer noted, he seems incapable of writing a dull sentence. The Life of Riley shows him to be a consummate performer of that alchemy of which only the great comic novelists were capable: he can make you laugh simply through his use of words.

Although packed with farcical episodes, The Life of Riley is at its funniest when Riley is left to meditate on his own increasingly dire situation. Here he ponders the human condition. "I am not, as the reader will perhaps have gathered, easily afflicted or cast down by what is called sordidity. Like Dr. Johnson, I have no great passion for clean linen. I have stood in company with my unseen garments - socks, underpants, vest - representing the elemental facts of existence, and felt, if anything, comforted by their reminder."

However, it would be wrong to class The Life of Riley as just a comic novel. As Colm Toibin observes in his introduction, Riley is a hybrid of Joyce's aspiring artists, Flann O'Brien's loquacious oddballs and Beckett's philosophical tramps and the natural successor to them all. He seeks nothing more than shelter, peace of thought, the occasional plate of hot scoff, a modest amount of sex and an immodest amount of drink; but his every attempt to secure these leads to chaos. He is a Modernist anti-hero, an Existential wanderer, an Angry Young Man and an artist manqué all rolled into one and this makes The Life of Riley an important stepping stone in the development of Irish fiction.

There are also many weighty themes at play under the surface levity of Cronin's novel. His characters invariably end up squandering their talent, Riley finds normal human relations impossible to maintain and loses all of his female companions is some poignantly-written scenes. Dread and desperation stalk this book. National identity is something to which Cronin gives particular thought, despising equally those who cling to their outdated cultural notions and those who ham up their Irishness for cash.

Those who have read Cronin's classic memoir of Dubin's artistic scene in the 50's, Dead and Doornails, shall be glad to know that his facility for hilarious descriptions didn't desert him when he moved into fiction. A racy, boisterous and buzzing portrait of an age long gone, The Life of Riley is a novel about the dangers of the bohemian life that the artists of this generation will find surprisingly prescient. It says much that when it ends, and ends abruptly, you are

left with an overwhelming appetite for more.

The Life of Riley

By Anthony Cronin

New Island

187pp