The Kindle era

Since, some two weeks ago, I avoided the cold damp miseries of our British winter by moving myself to southern California (and avoided disruption of my daily activities by moving my laptop with me), I have been investigating the world of self publishing by e-book – digital self publishing.

This is quite different from ‘vanity’ publishing; the means by which those who believe that they deserve to be remembered either for their literary merits, or for what they are or have done, pay up front to be published by a publishing house prepared to make such an arrangement, to have a minimum run printed and the book distributed to the retail trade. They take subsequently a pre-agreed share of any revenue earned.

Those who self publish by e-book pay nothing by way of setup fee or commitment to a minimum order. They provide their book in digital format to a facilitating house and decide for themselves matters such as hard back or soft back, layout, cover design and, importantly, price. The facilitating house signals the book’s availability by showing it on its website and produces (and delivers) against online order. It remunerates itself by taking a pre-agreed share of the price paid by the customer.

This is another example of how we are being liberated by the new communications technologies. In the same way that the power base of those politicians and newspaper proprietors who like to decide what we should know and when we should know it is being eroded rapidly by the world wide web, the power of the established publishing houses to decide which authors should be published is being taken rapidly away from them.

I was discussing the pros and cons of different outfits in the U.S. facilitating the self publishing of e-books with an old, much published, Californian friend when he said ‘I like the development of self publishing, it gives the author much more control and brings him closer to the reader, but don’t make any decision until you have thought about Kindle, where it is going and what it is going to do. I believe that within ten years or sooner, everyone now under thirty five, and most older than that, will have abandoned printed books and magazines. The book stores will be dead: so will most of the present publishers.’

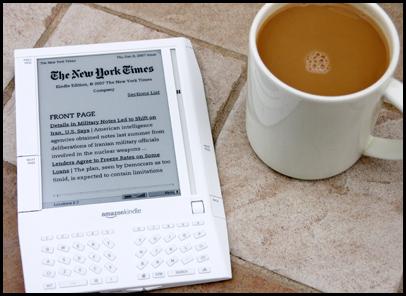

Amazon Kindle (as gleaned by me from my friend and Wikipedia) is a software and hardware platform developed by Amazon for displaying digital material selected by the user, including e-books, against online order. The first Kindle – the hand held reader which is the hardware part of the platform – was released to the market in late 2007 at a price of some $400 (€280): it sold out in five and a half hours. This device, the K2 and later K versions ‘support’ the Amazon Kindle platform as does an iPhone application named Kindle iPhone.

The Kindle is slim, light, nicely designed and user friendly. It has a ‘soft on the eye’ electronic ‘paper’ display and downloads the desired content either via Amazon Whispernet (no fee) or via AT and T’s international network. The turnable pages are roughly paperback size (the K DX has larger pages more suitable for newspapers and text books) and different fonts and print sizes can be selected. Currently it only displays black and white illustration. Those with an Amazon credit card account can order pay and download by a click button on the reader.

The Kindle was only useable in the U.S. until October 2009 when Amazon announced an international version with an inbuilt wireless modem providing connectivity in more than two hundred countries. This now sells worldwide at $259 (€180).

Amazon currently lists 360,000 titles available in digital format. Many of these are also available in normal printed format. Currently, in those cases where both formats are available, 48 per cent of purchasers are opting for the title to be downloaded. That startling statistic endorses my friend’s view of the position ten years down the road. So does another statistic. Last September the volume, in value, of books sold in e-book form in the U.S. was $16 million (€23m) – an increase of 171 per cent over the previous year. This strongly developing trend will be given a further boost when, apparently within two years, an even slimmer Kindle will be available with a large page size and capable of displaying material dependent on interplay between text and coloured illustration - such as Gray’s Anatomy and magazines.

Unsurprisingly others, particularly Amazon’s competitors such as the bookstore Barnes and Noble, are scrambling to enter this market opened up by Amazon with their own devices and platforms. But the ‘lead’ that Amazon has established in the public mind is demonstrated by the way in which newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times carry comment about ‘the Kindle Era’. That lead is now being emphasised by successful authors abandoning their traditional publishers and giving Amazon the exclusive right to distribute their works in digital (e-book) format.

It would clearly be undesirable for Amazon’s position to become consolidated into near monopoly but it surely deserves, and will earn, a rich reward for imagination and entrepreneurial (even if potentially predatory) initiative. There are some who are less admiring and more wary of Kindle and see it as an attempt by Amazon to secure a complete monopoly of book distribution. My response to them is that it is extremely difficult to maintain monopoly of distribution (see the reference to Barnes and Noble above) particularly in a country such as the U.S. which is singularly unfriendly to monopoly. Further, those sceptics should, perhaps, reflect on the benefits already flowing from the liberation of creative talent (commented on further below) and made possible by these developments – something that the Web, viewed as plumbing, with all its liberating potential has only partly achieved.

Unsurprisingly also, the Kindle is upending the book publishing and distribution industries and ‘all who sail in them’. ‘Old’ industries are rarely in the lead when it comes to developing ‘young’ technologies invading ‘their’ markets. Few, if any, makers of horse drawn carriages became makers of motor buses or cars. The thrusting young companies of San Francisco’s Silicon Valley developed ‘solid state’ devices to take important markets away from the older electronics companies who had built their positions on vacuum physics. And the new bio-technology companies such as Genentech (based also in San Francisco) got years ahead of many of the established pharmaceutical companies in the postulation and development of new therapies based on an understanding of molecular biology. The reason for this is obvious: those older companies expend their creative energies in attempting to defend what they have and, quite frequently, mounting anti-competitive forays based on cartel to bolster that defence. Frequently also they die in the attempt as change overtakes them.

That fate now seems likely to overtake many great names involved in the publishing (and distribution) of books. This, partly the result of self publishing (which is being given, already, a huge boost by Kindle) and partly the economic power of successful authors controlling their digital rights and able to deal directly with distributors, is for the good. It is as bad socially for the publication of written material to be repressed as it is for any other material. We do not know how many French or other ‘impressionists’ of merit, whose work we would have enjoyed, did not ‘make it’.

The present publishing system is extremely restrictive and repressive of creative talent. Publication depends on a publishing house deciding that a proffered work is ‘commercial’. ‘Commercial’ is a portmanteau word connoting many things. It covers author identity and reputation, topic attraction, literary style, length of manuscript, likely sales volume, possible television and other spin offs and, importantly, fit with the publishing house image. If thought necessary, work is made more ‘commercial’ by pruning, editing and re-formatting, even if the author does not like the result that much. And the system is supported by literary agents who, completely understandably, attempt to monopolise the channels by which material reaches the publishing houses for consideration: they make the first judgement as to whether a work is likely to be deemed ‘commercial’.

Undoubtedly most publishers and agents are culturally civilised and have benign intentions - even if those intentions are informed only by enlightened self interest. But, as in the case of the impressionists, we do not know of how much we may have been deprived. A well known ‘near miss’ was the case of The Story of San Michele by Axel Munthe. That beautifully written fantasy about the creation of a remarkable home high on the bluffs of Capri became an international best seller. It was turned down over many years by numerous publishers as not being commercial or without merit before John Murray took it on in 1929. On the other hand, to make an ambiguous remark, the system has given us the literary merits of Jeffery Archer and Katie Price (pace Jordan and Rebecca Farnworth).

If life is difficult for authors, it is even more so for those – and there are many of them - who have the skills to illustrate books. The publishing houses like books suitable for illustration to be illustrated by ‘their’ illustrators. This makes it difficult for authors and illustrators to collaborate ‘as they go along’ in the expression of their creativity. A manuscript already illustrated is not welcome. Self publishing and the coming Kindles will change that! That is one of the things my Californian friend was driving at.

And, talking of artists, those who draw and paint need no longer be dependent on galleries for the public to see their work. With the help of facilitators, it will be digitised and downloaded for inspection by the rest of us on our hand held device at bed time.

The Kindle Era will be great for those who create and those who enjoy their creations: they will be brought closer together via an open market and in an interactive way. I look forward to it greatly - in California, Britain and everywhere else.

With thanks to Open Democracy.