Ireland third most popular tax haven for FTSE100 companies

Our corporation tax rate was thrown into the spotlight once again this week when it was revealed that Ireland is the third most popular ‘tax haven’ in the world for subsidiaries of UK FTSE 100 companies. On Tuesday (11 October), UK based charity ActionAid released a comprehensive dataset and report on the location of these subsidiaries. It found that a quarter of all FTSE 100 company subsidiaries are located in tax havens. The charity’s research is based on information that had never been disclosed or analysed before this year.

ActionAid says:

"UK law compels companies to report all of their subsidiary companies, together with their country of registration. When we looked for this information in early 2011, we discovered that more than half of the FTSE 100 were not complying with this legal obligation. When enquiries to individual companies failed to persuade them to disclose the information, we submitted complaints to Companies House, forcing the disclosures as part of companies’ annual returns."

While there is no standard definition of a ‘tax haven’ ActionAid’s dataset uses a list compiled by the US Government Audit Office (GAO) in 2008. That report notes:

“There is no agreed-upon definition of a tax haven or agreed-upon list of jurisdictions that should be considered tax havens. However,various governmental, international, and academic sources used similar characteristics to define and identify tax havens. Some of the characteristics included no or nominal taxes; a lack of effective exchange of information with foreign tax authorities; and a lack of transparency in legislative, legal, or administrative provisions.”

Ireland, Malta and Luxembourg are the only EU states included on the GAO’s list. ActionAid also included the Netherlands and the US State of Delaware - both are acknowledged to offer tax and minimal disclosure advantages to foreign companies.

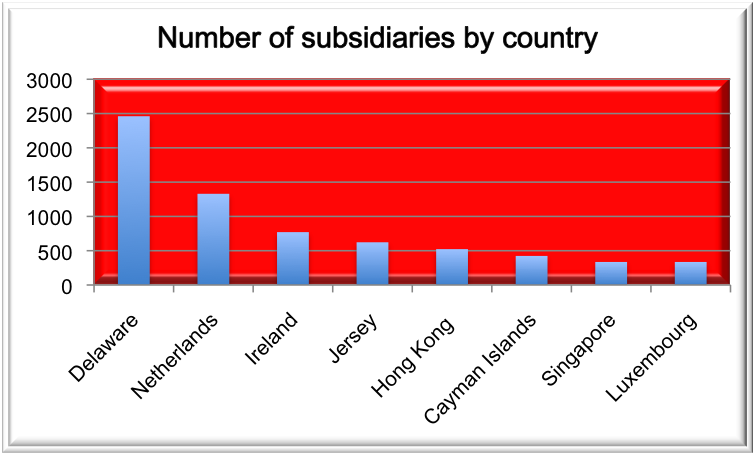

The US state of Delaware is the most popular location for British FTSE 100 companies to locate their subsidiaries - 2,461 subsidiary companies are based there. The Netherlands is the next most popular location, with 1,330 subsidiaries. Ireland comes in third, with 771.

It should be pointed out that there are legitimate reasons for companies to locate their subsidiaries in jurisdictions categorised as tax havens. In other words, a subsidiary company’s being located in Ireland does not prove that that company is engaged in tax avoidance.

Advertising company WPP has 43 subsidiaries located in Ireland, according to the report. The company moved its tax domicile here in 2008. At the time of the move its prospectus explained: “This should provide the opportunity to reduce the overall tax rate.” According to the Guardian, “It has indicated that it is ready to return to the UK for tax purposes in 2013 if proposals in George Osborne's budget this year to relax the rules on taxing foreign subsidiaries are enacted.”

Obviously, British companies are not the only ones taking advantage of Ireland’s corporation tax rate. As Simon Johnson and Peter Boone noted in a 2010 piece for the New York Times:

“All sorts of businesses — from computer services like Google and Yahoo, to drug companies like Forest Labs — …set up corporate bases and wash profits through Ireland to keep them out of the hands of the Internal Revenue Service.”

In another piece, the same authors describe Ireland as “one of Europe’s most impressive tax havens”. They go on:

"It is possible to set up a corporation in Ireland, channel sales through that head office (with some highly complicated links to offshore tax havens in order to avoid paying Irish tax) and then pay a minuscule corporate profits tax. Ireland boasts a large industry of foreign 'tax minimizers' that do this, but these tax minimizers hardly employ any people. Nearly one-quarter of Irish GDP comes from the profits of these ghost corporations."

One company that is extremely efficient at minimising the amount of tax it pays is Google. Interestingly, the actual tax rate paid on net profits by Google in Ireland in 2009 was around 20%. Google Ireland made an operating profit of €45m last year, and paid corporation tax of €9.6m. The company’s gross profit was €5.5bn, meanwhile. Where did that extra €5.467bn go? To Bermuda, where the corporation tax rate is 0%. This tax strategy is entirely legal: the intellectual property in the company's brand and technologies resides in Bermuda, after all. The issue, then, may be less Ireland’s headline rate of 12.5% corporation tax than the ease with which companies can, as Bloomberg describes it, “legally shuttle profits into and out of subsidiaries there, largely escaping the country’s 12.5% income tax.”

The cost of tax havens

ActionAid says:

"The roaring trade undertaken by tax havens leads to the tax burden being shifted from the companies and rich individuals who use their services, on to ordinary people and businesses who comply with their tax obligations. At the same time, the loss of government revenues means lower investment in public services."

According to Paul Murphy, Socialist Party MEP, Ireland’s tax policies “contribute to a race to the bottom in taxes on corporations. This creates a downward pressure generally and means that companies feel free to locate themselves with the ‘lowest bidder’. The result is less tax revenue from companies that could be spent on public services and more profits for big business.”

One argument for the maintenance of Ireland’s ‘tax haven’ status is that it attracts foreign investment and creates jobs. If a side effect of this is that some companies set up brass plate offices here purely for tax purposes (with no employment gain), that’s unfortunate, but unavoidable. Many multinationals do, after all, employ and pay real humans. However, as Conor McCabe explores in detail in his book Sins of the Father; taken in total, the multinational sector is at best tangential to the real economy – both in terms of employment gains and returns to the Irish exchequer. And as Michael Taft has noted - taking multinational computer services as an example – in that latter sector one person is employed for every €1,300 million in sales; in the indigenous sector, one person is employed for every €150,000 in sales.

As the Government prepares us all for another round of belt-tightening in December, and the US Internal Revenue Service begins an audit of Google’s tax strategies, it’s probably not a bad time to ask, once again, whether Ireland’s tax policies make sense to anyone - other than coporate tax accountants, that is.

Image top: Eire Sarah.

{jathumbnailoff}