'I like to play with words. It's fun and it's my job.'

Terry Pratchett, literary superstar and cult hero, performed a publishing miracle when he dreamed up the universe of Discworld 30 years ago, and his magic is far from used up. Speaking to a Dublin audience recently the wizard of fantasy fiction talked about his inspirations, his struggle with Alzheimer's disease and his new novel, Dodger. By Ed O’Hare.

So you're one of the most famous authors alive, an iconic figure with an army of devoted fans big enough to take over the world. So your books have sold 80 million copies and have been translated into 37 languages. So the elaborate fantasy world you created has become a contemporary phenomenon and something that has brought joy into the lives of innumerable readers. So you've received a pile of accolades, awards and a knighthood. So you've been diagnosed with a terminal illness that will gradually strip away your identity and leave you with no memory of who you were. If all the above apply to you, what do you do? If you are Terry Pratchett the answer is: you write like hell.

It's nearly 30 years since the man who wrote science-fiction in his spare time tried something not completely different and published the first of the Discworld novels, and it's no hyperbole to say that the publishing world is still reeling from the impact. Pratchett's books triggered a revolution in fiction and their popularity has only increased. To paraphrase the blurb which used to appear on the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, the global population can be divided into two camps: those who have read, loved and enjoyed Pratchett's books and those who are about to read, love and enjoy Pratchett's books.

Pratchett's Discworld series proved once and for good that 'cult' audiences could be the most lucrative of all and set thousands of other writers, agents and editors scrambling to recreate their success. It's a fairly safe bet that without the Discworld series Harry Potter's broomstick might never have left the ground, the Hunger Games would never have been fought, Skullduggery Pleasant wouldn't have cast a spell and Artemis Fowl's criminal schemes would never have got off the drawing-board.

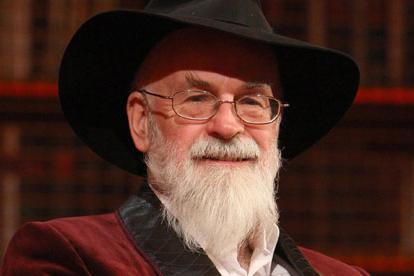

And yet the man responsible for all this seems entirely reluctant to pass on the baton to a new generation. Seated on an ornately carved oak chair, dressed in a decadent-looking chocolate coloured silk smoking jacket and wearing his trademark wide-brimmed hat, the author's domed forehead and luxuriant beard only confirm the image of Pratchett as a latter-day wizard. And yet with one word he brings matters firmly down to earth. As his achievements are listed Pratchett adjusts the sales figures of his books by ten million. “Eighty” he states firmly, “Eighty million.” One wonders how many authors have ever had the chance to make a similar correction.

If Pratchett initially cuts a benign, wacky figure, this impression does not last for long. Indeed, he proves a spiky, even combative interviewee. One senses that his many, many years doing the rounds at sci-fi and fantasy conventions have left him weary of the standard q & a routine, and he seems determined to take the conversation where he wants it to go. Today his business is to promote Dodger, his new novel and a reimagining of the story of the pint-sized pickpocket originally introduced in Oliver Twist.

Pratchett reflects upon the book's genesis. A few years ago he read London Labour and the London Poor, an 1840 account of the lives and working conditions of that city's indigents and labourers. Instantly Pratchett realised that the book in his hands was “a goldmine.” As he puts it, “Serendipitous reading is the patron goddess of all narratives” and this was only confirmed when he learned that Henry Mayhew, the author of London Labour and the London Poor, was accompanied on his journeys into London's most impoverished districts by his rather more famous friend, a novelist with a social conscience who knew a thing or two about poverty and wealth, Charles Dickens.

London Labour and the London Poor was packed with the kind of grim details that are invaluable material for the novelist. As Pratchett explains, Mayhew's book depicts whole families living in conditions “not so good as that of swine” and the shocking statistics about disease, alcoholism and deprivation he collected were intended “to shame the government into acting”. It also gave one of the first detailed accounts of the working lives of London's poorest children who found unenviable employment as chimney-sweeps or worse still as Toshers, who spent their days sifting through the contents of the sewers in search of valuable materials.

Mayhew's book inspired one of those classic 'what if' questions: what if Mayhew and Dickens had come across a real adolescent master-criminal called Dodger? It had been a while since Pratchett had written an alternative historical novel of this kind and he found it great fun to appropriate an existing character like the Dodger and “take him and move him through the world”. He enjoyed writing about someone who sees life only in terms of two questions: “How much?” and “What's in it for me?” More than anything Pratchett revelled in deconstructing the official version of Dodger's story given to us by Dickens in his own inimitable way.

Dodger is the second Pratchett outing in succession not to be set in the Discworld universe (he recently co-authored a novel with the acclaimed science-fiction author Stephen Baxter called The Long Earth). Although the Discworld books will be his legacy, Pratchett sees it as “good for my soul to get away from them for a while”. For Pratchett, Dodger belongs in the grand tradition of the “fantastic historical” novel because it is “a fantasy based on a reality.” He says that he has always been fond of works of fiction which “take a person who doesn't exist and put them in a world that did” and he was an early fan of George MacDonald Fraser's rollicking Flashman series. The key to such books, he believes, lies in measured research. He dislikes historical novels which confound the reader with too much historical information but insists that “when you've got a certain amount of detail nailed down you feel happy” and the world you've created is one the reader will believe in.

One can't help but think that Dodger, the story of a poor boy who uses his sharp wits to better himself, must have some parallel with Pratchett's own history. Born in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, one of the most neglected regions of Britain in 1948, Pratchett quickly discovered that books could be a passport out of his humdrum rural surroundings. He describes himself as the sort of “strange adolescent” who thrived on the new ideas books contained and believes more ardently than ever that the “best gift a parent can give their child is an enjoyment of reading, a love of letters and words”. His parents introduced him to the local library at an early age but were perturbed when they found that he had worked his way through its entire holdings “and enjoyed them all, especially the ones I shouldn't have been reading”.

Pratchett's love of books allowed him to escape a life of monotony but the day-job he secured, press officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board, wasn't exactly riveting either. Whenever an opportunity came along Pratchett scribbled away and realised that he was getting as much fun out of writing his own novels as did from reading those by others. Within seven years he turned professional. It is one of the classic clichés about writers that the more humble their origins the more impressive their work ethic, but in Pratchett's case it happens to be true. He has been mind-bogglingly prolific (writing two books almost every year since 1983) and says that he has “always got at least one more book” on the go at any time. He is notoriously upfront about the commercial side of what he does and admits that he measures his life in terms of the amount of time “I could be writing” and cannot look at an audience at a convention or literary festival without thinking about the good news this means for the till. Neither does Pratchett dwell on the work he produces. As much as he enjoys putting a novel together, once it is finished “it disappears from my radar,” as he needs “all my available brain-space” for the next one.

That Patchett has been able to maintain such a formidable rate of output in the last few years has been even more incredible. The miniscule number of people who never knew about him through his books now know Pratchett as the world's most famous Alzheimer's sufferer. It's almost five years since he left readers the world over devastated when he went public about his diagnosis, and although to the casual observer he looks robust and his mind has retained its razor-sharp edge he confesses that his condition has deteriorated at an aggressive pace. Pratchett can no longer read and must dictate his work using a sophisticated computer called Betsy, which he can access from anywhere on the planet. Of all his recent projects the ones which have won him most praise are the two harrowing documentaries Pratchett has made for the BBC which followed his daily battle with the disease. In the second of these he soberly and eloquently considered the human right to euthanasia, and his bravery in challenging the taboos which surround it was universally commended.

While Pratchett doesn't deny how seriously ill he is he has not let despair affect his outlook on life. After all, this is the man whose comic vision permits a world to be flat and held up by four elephants who ride on the back of a giant turtle that swims through space. Years ago Pratchett even made Death himself into a scene-stealing fictional character, often voted the most beloved of all his creations. Indeed, while the grandiosity of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy and the moralising of C.S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia scare off plenty of modern readers, the keen, warm irony of Pratchett's work and the open secret that Discworld is our Earth with all its silliness exposed have sustained the series. Like Douglas Adams's Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series, they take us into a completely different reality just to show us how bizarre, baffling and illogical our supposedly 'ordinary' lives are.

Pratchett has been quoted as saying that he cannot die if he is working on something. Unsurprisingly, this means he is juggling more books now than ever. Fans of Discworld will be delighted to know that Pratchett has a new, and as yet untitled, novel all but ready, and it will be intriguing to see if it matches or even trumps the success of its predecessor Snuff, the third-fastest-selling novel in history. Real Pratchett boffins will also be glad to hear that a fourth volume in the acclaimed Science of Discworld series (written in partnership with his old friends, the distinguished scientists Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen) is also on the way, while a sequel to The Long Earth is already in the works.

The most interesting of all Pratchett's current projects, and the one he mischievously says he is quietly working away at “when I've got nothing else to do”, is his autobiography. He has let on before that a memoir was in the pipeline but now he seems in earnest about it. Suddenly he takes his audience back to the days of his boyhood. “My family was poor,” he explains “but in those parts we didn't realize how poor we were because nobody was rich.” Pratchett recalls that “all anybody had were bicycles” and this triggers a powerful memory. “I remember one Sunday evening walking home with my mother and we reached a local landmark called the Dip, stopped and looked up. And there they were. My father and all the other working men returning by bicycle in one great flotilla. All smoking pipes and all gliding home together at sundown. It was such a strange sight that it stayed with me all my life.” Absolute silence reigns in the auditorium. The wizard of Discworld has worked another magic spell right before our eyes. {jathumbnailoff}