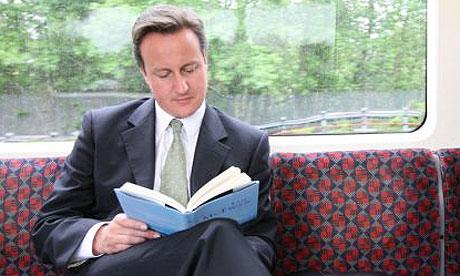

A history lesson for David Cameron

As the British election reaches its climax, Nigel Keohane's book The Party of Patriotism charts the evolution of the British Conservative Party through the twentieth century. By Dr. William Mulligan.

The "seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century" was how the American diplomat and historian, George Kennan, described the First World War.

However from the perspective of the Conservative Party, the war was a moment of regeneration and renewal. Having lost power in the 1905 election following a fratricidal struggle over tariff reform the Conservative (or Conservative and Unionist Party to give it its proper title) suffered two further election defeats in 1910. The Parliament Act of 1911 diminished the role of the House of Lords, a major pillar of Conservative power and influence.

Yet between the coupon election of 1918 and the surprising defeat in 1945, the Conservatives dominated British politics.

The intervening years of the First World War, therefore, occupy a central place in the narrative of Conservative ascendancy in twentieth century British politics.

Nonetheless, as Nigel Keohane points out in a cogently argued and well-researched book, historians have paid less attention to Conservative success than to the ‘strange death of Liberal England’, to use George Dangerfield’s phrase, in these years.

Keohane argues that the Conservative response to the war, articulated through the rich and malleable language of patriotism, was effective in meeting the party political, ideological, and military demands of total war. The party’s success was far from inevitable and its leaders and local organisers had to adapt their pre-war policies to entirely new circumstances.

Many of the major changes in the war – the placing of Home Rule on the statute book, the widening of the franchise to all males over 21 years of age and most women over 30 years of age, and the intervention of the state in the economy and the private sphere – would have been anathema to the pre-war Conservative party.

Patriotism held the party together and enabled it to navigate the tides of war more successfully than its great nineteenth century rival, the Liberal party. Keohane is careful to point out that patriotism was not an exclusive Conservative language before the First World War.

Liberal varieties of patriotism were sceptical of state intrusion and regarded war as a pursuit foreign to a true-born Englishman. Conservative ideas of patriotism were closer to the requirements of wartime. The emphasis on national cohesion, sacrifice, and empire came more easily to Conservatives than to Liberals.

Crucially the Conservative varieties of patriotism offered a means of connecting material interests and emotional appeal. When the Labour party called for a levy on capital to pay down Britain’s war debts, the Conservatives responded with a pamphlet reminding readers, including many ordinary men and women who had bought war bonds: "Remember those who saved money helped to save the Empire".

The exigencies of the war and the language of patriotism enabled the Conservatives to change policy without splitting the party in three significant areas.

First the party dropped, albeit reluctantly, its opposition to Home Rule. The fixation on Ireland, which had characterised Conservative politics before 1914, was now replaced with a broader vision of empire. The support from the Dominions in terms of men, money, and supplies, invited Conservatives to view empire as the essential pillar of British national security. That Dominions helped Britain in its hour of need made the prospect of a Home Rule Ireland seem less dangerous, even if it remained distasteful. From this perspective Conservative grappling with the Free State’s status within the Commonwealth after 1922 came as little surprise. It was part of a wider debate about imperial affairs, rather than a simple Anglo-Irish squabble.

Second, Conservatives became much more amenable after 1914 to the expansion of the electorate. Patriotism meant that fighting men could not be denied the vote, nor could women who had contributed to the war effort. Besides, party activists were confident that returning soldiers and women would vote Conservative and balance the working class vote, strongly linked with the emerging Labour party and the strengthened trade union movement.

Finally the Conservatives encouraged state intervention in industry and certain areas of social life to ensure that the war was prosecuted with as much energy as possible. Keohane shows how the Conservatives embraced the imperatives of ‘total mobilization’ during the First World War. There was far less hand-wringing amongst Conservatives than amongst Liberals over conscription, one of the most radical changes in civil-military relations in modern British history when it was introduced in 1916.

The major landmarks of domestic British history – the Glorious Revolution, the unions of 1707 and 1800, and the emergence of the welfare state in the 1940s – owed much to the pressures of great power conflict. The First World War wrought changes of similar significance, notably the fracturing of the Anglo-Irish Union and the introduction of universal male suffrage.

Keohane charts with great skill the mix of political opportunism and deeply-held conviction, which shaped the Conservative response to the war and concludes pithily and aptly that not alone had the Conservatives fought to make the world safe for democracy, but that they had also succeeded in "making democracy safe for the world".

The Party of Patriotism. The Conservative Party and the First World War by Nigel Keohane

The Party of Patriotism. The Conservative Party and the First World War by Nigel Keohane