Garda vetting system in need of reform

The Garda vetting system is in need of reform in order to make it more efficient and user-friendly. By Sandy Hazel.

Garda vetting is in the news thanks to its long waiting list and the burden of bureaucracy it places on businesses, community groups, volunteers and prospective adoptive parents. So what is the problem with the system and what is being done to fix what many see as a flawed process?

“The original idea of vetting was to ensure better protection for children…to produce some peace of mind. Intended to supplement good recruitment practice, it has become a major barrier to many voluntary groups doing front line work,” says Michael McLoughlin from Youth Work Ireland (YWI).

McLoughlin, whose organisation processes thousands of vetting requests annually, believes there can be “over vetting” and calls for a more intelligent approach. A system of “mutual recognition” and sharing of data between organisations, with applicants’ consent, would remove a large amount of the demand in the system and the duplication of many requests, he says.

Other organisations agree that the fault lies not with the Garda Central Vetting Unit (GCVU) but with legislation. “The Garda Vetting Unit cannot be seen to criticise the system, but it is pursuing changes to the legislation. Many of us know that it has its hands tied behind its back when it comes to the process,” says a concerned community worker.

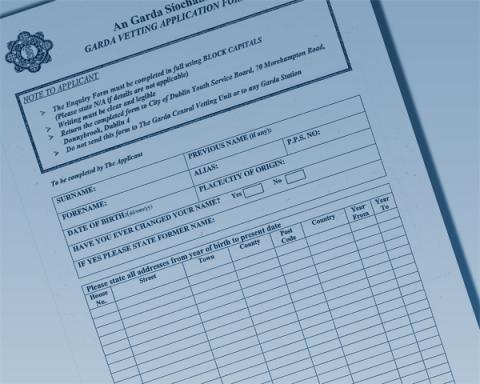

Delays too can be at the applicant organisation side. The requirement for hand written hard copies makes for error margins and causes further delays in getting forms to the vetting unit in the first place. If an applicant has lived outside Ireland for some time there can be further delays. The HSE requires its candidates to supply police clearance certificates from all countries resided in, dated after they left.

Some community employment schemes will not accept applications from those who have lived “outside the island of Ireland” for certain periods. It is unclear why this is so, particularly in a mobile European jobs market.

Calling for better legislation, Yvonne McKenna of Volunteer Ireland says that an online system will help when re-vetting. “It would allow for identification numbers to be given which will help with portability of the records. If I wanted to move job I would just be able to give my number so records up to that point could be retrieved more easily.”

The value placed on vetting can be misplaced too. Vetting is an “out of date retrospective account as soon as it is issued” explains McKenna. “We must be careful not to use it as a panacea,” she says. Those who have “other intentions with regard to vulnerable adults or children may not have a criminal record anyway,” she says, and adds that the Garda Vetting Unit is doing what it can with very limited resources.

McKenna feels that legislation will be the only way to improve the process. “Legislation will allow for more technological processes to be introduced, making the system more efficient and effective,” she says. Legislation will come in the shape of the National Vetting Bureau Bill. It is at an early stage of the Dáil process and organisations will make submissions. The bill will provide for the establishment of a National Vetting Bureau and some see it as operating separate to the Gardaí – much like the Criminal Assets Bureau.

But bills tend to move slowly towards enactment, and pressure needs to be maintained to prevent it languishing on the list. Many in the sector cite the system in Northern Ireland, Access NI, as one that works well. The Access NI programme has undergone a review recently in order to implement “a more common sense approach”. Its press office says “the Vetting and Barring Scheme (VBS) review recommended that only those individuals working most closely with children or vulnerable adults required to be checked. The concept of an independent organisation to make barring decisions was retained, but the requirement for a central registration process was scrapped to be replaced by criminal record checks that would be portable - thus no longer requiring individuals to undergo multiple checking with different employers.”

The Access NI programme will use online processes “after the passage of the Protection of Freedom Bill and when the appropriate IT systems are operational. “This is expected to be early 2012,” said a spokesperson. The northern system operates on a “full cost recovery” system – in other words, it charges fees to applicants. It does not charge for volunteers’ applications. Crucially, it also operates a user-friendly website with forms freely available for varying levels of disclosure.

Minister for Justice Alan Shatter has already responded to vetting concerns by increasing the staff at the vetting unit. There are currently a total of 89 Gardaí and civilian personnel assigned to the unit, which provides the service to over 18,000 organisations. “Legislative proposals… will necessitate consideration of a wide range of issues including information sharing with other relevant bodies,” Shatter told the Dáil in April. “It will also…need to protect the constitutional rights of all citizens. Any legislative proposals will be announced and brought forward in the usual way,” he said.