The game is rigged

The plan to postpone the payment of the Anglo Irish promissory note until 2025 is part of a wider attempt to save the asses of the banks by maintaining the fiction they are not insolvent. By Donagh Brennan.

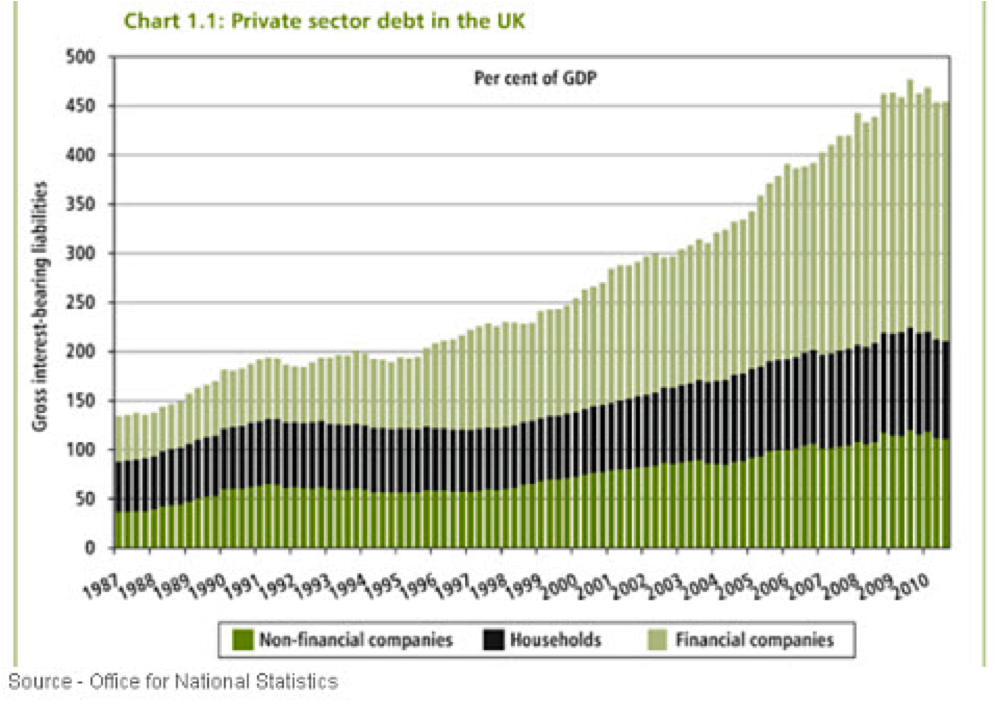

Ann Pettifor has argued regularly that the problems in the British economy stem from the vast level of private sector debt, principally in financial institutions rather than with public sector debt.

Now, she says we are on the verge of a new credit crunch. The indications for this can be seen in the decision last week to provide an additional €529.5 billion to European banks for three years of unrestricted lending, instead of the one year limit put on the previous LTRO. It’s what the banks did with this flush of cheap money that is important: they placed it back on deposit with the ECB, earning an interest rate lower than the one they are being charged for taking the loan in the first place. They know that the interbank market and the banks involved in it are insolvent and prefer to absorb the cost, placing it with the only bank they know is safe.

“It appears banks are no longer lending to each other. Just as the credit crunch of August 2007 was heralded by a freezing up of inter-bank lending, so history is repeating itself. According to the FT, banks deposited a record €777bn overnight with a state-backed bank, the European Central Bank last week, up nearly two thirds from the previous day.

Banks borrowed from the ECB at 0.5% on one day, and then the next, re-deposited funds with the ECB for less – 0.25%. This would normally be odd behaviour, because banks could earn a great deal more by parking the money with other banks in the inter-bank market. However, because they know the truth of the solvency of other banks, that market scares the hell out of them. Which is why they are parking their (our) money with a bank that cannot go bust: the taxpayer-backed ECB.”

The problems for the banks are made worse by austerity:

“The fact is that for every firm that loses a government contract, and for every person made unemployed, there will likely be a defaulter on a loan; for every weakening firm and unemployed person, there will be one more customer cancelling an order or snapping their purse shut.

For every default, and for every lost customer, there are weakening balance sheets – for both firms and banks – making it harder for the financial and corporate sectors to recover from the crisis, and deal with their huge debts. Indeed austerity makes their predicament much, much worse.”

Irish banks are certainly not out of the woods either - far from it. A portion of the mortgages currently on the books of Irish banks have been securitised - essentially placed off-balance sheet in special purpose vehicles. These SPVs are not regulated and allow the banks to sell on the risk associated with the mortgage while maintaining their capital reserve requirement.

As Conor McCabe explains here, this allows them,

“for example, to bundle the risk associated with thousands of residential mortgages all together and sell that risk on as a tradable commodity - as with Ulster Bank, which issued thirteen residential mortgage backed securities of which seven remain outstanding."

Indeed Ulster Bank, which is owned by the Royal Bank of Scotland, mentions that its funding includes commercial paper and securitisation:

"Ulster Bank Group is funded from a number of sources namely, retail deposits, corporate deposits, mortgage backed promissory notes, certificates of deposit through Ulster Bank Northern Ireland, the inter-bank money markets, European commercial paper, floating rate notes, securitisation, and as a core subsidiary of the Royal Bank of Scotland Group (RBS) we fund an element of our balance sheet directly from RBS."

These securitised entities, however, only work for as long as the loans are ‘performing’. To find out what happens to these credit derivatives when they stop performing see the Subprime Mortgage Crisis for details. To what degree are our Irish ‘pillar’ banks involved in this market? Well, we know that Ireland is top of the table when it comes to financial vehicle corporations in the Eurozone, and these include mortgage-backed securities, so the answer is more than likely ‘significantly’.

According the Financial Times RBS is availing of the second Long Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) to the tune of €5 billion:

"RBS, which took about €5bn of LTRO money in December, is set to take a similar amount in Wednesday’s auction, according to senior bankers. The group’s eurozone exposure is focused on Ireland, where it owns Ulster Bank."

So the vaunted plan to postpone the payment of the Anglo Irish promissory note until 2025 is part of this wider attempt to save the asses of the banks by maintaining the fiction that they are not insolvent.

While governments are allowed to undermine the capital reserve of private banks through austerity - despite the systemic risk that that entails - they are not allowed to default on debt that would have the same impact, even though the debt incurred is not the responsibility of those who are being forced ultimately pay for it.

The reason for this, of course, is because it is a mechanism for the transfer of wealth from people who pay taxes, whether through labour or more increasingly, indirectly through consumption taxes, to those who don’t pay tax and who are responsible for the debts in the first place. As Andy Storey of the Anglo: Not Our Debt campaign pointed out in a press release response to the initial news of a postponement, a rescheduling of the promissory note reduces the chances of cancelling this odious debt and will more than likely cost us more:

“We do not know the interest rate on this new loan that is being taken out to cover the €3.1 billion, so we could end up accumulating yet more debt in years to come, bequeathing a legacy of even greater hardship to the next generation.

The government is reducing our chances of writing down this unjust debt. Had the government cancelled the original payment outright this would not have been a sovereign default, but cancelling the payment now due in 2025 would constitute a default. Wehave boxed ourselves into a corner here, making it harder for us to write down this illegitimate debt in the future, whereas this is something we could and should have done right now.”

Well, we have an indication now of the interest rate: 6.8% according to Patrick Honohan before the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform yesterday afternoon. This apparently is part of the strategy to "keep the interest rate quite low" but only moderately so.

Basically there was always going to be some form of restructuring. However, although it may amount to a slight reduction in the cost on the interest rate its function is to copper-fasten the payment, even though the money being taken from the State (from General Government Debt) is being paid back to the State (the Central Bank of Ireland).Once repaid it will promptly vanish!

So it would seem that Ireland is being forced to repay for a ‘systemic’ and not an economic or fiscal reason.

This rescheduling is all about ensuring that insolvent private banks can maintain their ‘forebearance‘ and - despite the evidence of the collapse of the inter-bank market (the hallmark of the previous credit crunch) - can sustain the private money circuit, where banks create money through the issuing of new loans and restructuring debt within a speculative marketplace.

After all, with a Fiscal Compact attempting to politically lock in austerity to future budget decisions this 2025 bond with its CDS ancilliary and its almost 100% guaranteed return, would become a valuable commodity in its own right. {jathumbnailoff}

Originally published on Dublin Opinion.

Image top (part of the Romantic Ireland: From the Streets exhibition): Eadaoin O'Sullivan.