Enough gender-stereotyping – We get the message

We owe it to both young women and men to change media messages which repeatedly reinforce harmful norms of masculinity and femininity. By Clara Fischer.

With the drama of the Oscars over for another year, it might be time for reflection on the messages the film industry, and particularly Hollywood, is conveying on a near-global scale. Messages in film? But surely the entertainment industry is simply about that: entertainment? Not so: research shows that what might seem like light-hearted comedy or action-packed drama, is in fact increasingly gendered – that is, it portrays women and men in pointedly stereotypical ways. Worryingly, this phenomenon is having extremely negative effects on women and girls. A recent report by the American Psychological Association cited impaired cognitive ability, depression, low self-esteem and eating disorders as consequences of the sexualisation of women and ever-younger girls through the media.

While films constitute only one particular aspect of the onslaught of objectifying and sexualised images within the larger 24 hour media cycle, they give us a particular insight into the cartoonish nature women are assumed to hold, but also to accept as audience members. Women usually star as the love interest, the princess to be rescued, or as the general supporter of the male protagonist, lurking somewhere in the background as a Side-Show Berta. Alternatively, as we know from such movies as Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, women are hyper-sexualised and dangerously assertive. This latter variation on the theme should not be confused with a kind of liberated and independent agency, but rather constitutes another example of the reductive and objectifying view described in the literature as the ‘male gaze.’ Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder, as they say, but who is the beholder?

Certainly the filmmakers, producers, and studio bosses are overwhelmingly male, and overwhelmingly white and upper/middle class. Is it any wonder, then, that their experiences and stories are told, while women’s fall to the wayside? Even when women’s stories are told, though, they usually come in chick-flick form, which means they revolve around getting, keeping, or regaining a man – hardly a faithful depiction of the very complex lives we lead, yes, as partners, as mothers, as lovers, but also as workers, as leaders, as teachers, as writers, as politicians, and the myriad of other roles we may adopt in our daily lives.

A simple way of highlighting the lack of meaningful portrayal of women in movies is the Bechdel test, developed by Alison Bechdel in her comic strip, The Rule. According to the test, a film has to fulfil three criteria to pass: 1) the film has to have at least two women in it 2) these two women have to talk to each other 3) they have to talk to each other about something other than a man. This minimum of women’s relatively substantive inclusion in film is rarely achieved. Indeed, the majority of our most cherished movies fail to fulfil the principles of the Bechdel test. That is not to say that these movies can’t be good or inspiring pieces of cinema, but rather that the clear absence of women in film is a systemic problem. It is the sheer scale of women’s omission from movies, which makes the test so powerful and damning.

As noted, on those rare occasions where women do star in more sustained roles, perhaps even as the protagonist, those roles are increasingly stereotyped. Not only is this trend particularly damaging for younger female viewers, who adopt self-objectifying attitudes and behaviours, but it feeds into a larger raunch culture which ultimately disempowers women by promoting women’s sexual availability or physical appearance as the sole measure of our worth. The financial return for such a culture is of course handsome: the peddlers of beauty and slimming products, of unnecessary surgical procedures, and of dietary programmes and fads are indeed rewarded by the heightened anxiety women feel about their bodies, and ultimately, themselves.

And yet, there appears to be a weakness in this profit-driven model of women’s objectification: women might actually opt out. In a recent interview, Meryl Streep made this point by noting that the clichéd depictions of women in film might actually drive women away, thus leaving the profiteers minus a fairly large demographic. Films such as MissRepresentation, which highlight the complex and often negative role the media plays with regard to women’s portrayal, have also met with a level of enthusiasm which clearly indicates a groundswell against the stereotyped images women are bombarded with on a continuous basis. It seems that the mainstream movie industry has confused the beholders of beauty, their female viewers, with the reductive cartoon characters they assume them to be, instead of recognising them as the critical, thinking human beings they really are.

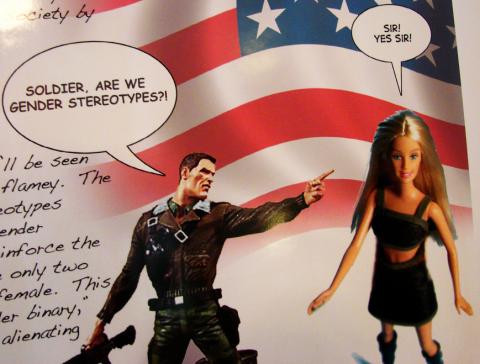

While opting out and critically engaging with the media is a viable option for media-literate adult audiences, it is less so for those who are still developing a sense of themselves. We owe it to these young women and men – for gender-stereotyping similarly skews boys’ attitudes and identities – to change the media messages, which repeatedly reinforce harmful norms of masculinity and femininity. One way of doing this is by simply taking our purchasing power elsewhere, by withdrawing economic support from the culture of objectification. If we believe Simone de Beauvoir’s famous dictum that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”, we seriously have to question what kind of women, and men, our society is fostering. {jathumbnailoff}

Dr. Clara Fischer is a co-ordinator of the Irish Feminist Network and holds a Ph.D. in feminist theory and political philosophy.

Image top: istolethetv.