Enduring legacy of the Beatles lives on

Legendary. Genius. Phenomenal.

Superlatives such as these rear their ugly faces far too often in popular usage. They are cheapened in a world of short-term disposable celebrities, where questions over the talent or wealth of said celebrities are hushed by a media world which pilfers to commercialism over public interest.

But.

When it comes to The Beatles...

From the silliest vaudeville (Maxwell’s Silver Hammer) to the politicised Revolution, from rock ‘n’ roll (Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey) to lullaby (Good Night), from the impassioned Something to carefully crafted pop – dare I say it – genius (Help, Drive My Car, Can’t Buy Me Love, Penny Lane, Hey Jude, too many more to mention), acoustic numbers (Blackbird, Mother Natures Son) and psychediala to boot (Tomorrow Never Knows, Strawberry Fields Forever, Across the Universe), The Beatles’s music still lives on.

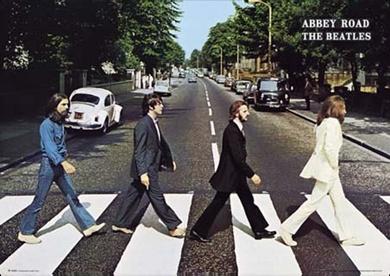

(Picture: The cover of Abbey Road)

Recently published by Cambridge University Press, The Cambridge Companion to The Beatles is further evidence of their lingering influence on contemporary culture.

The Companion offers a historical viewpoint, taking the reader from the earliest days of The Quarrymen, the hectic years of the 1960s, to the mixed fortunes of the former Beatles’ solo careers.

Edited by Kenneth Womack, Professor of English at Penn State University’s Altoona College, there are also chapters on The Beatles' pioneering use of the recording studio as an instrument unto itself, the influence of The Beatles on trends in fashion and popular consciousness in general, and a musicological essay by Walter Everett on their use of free phrase rhythms.

In the early days The Beatles were unique in their ambition to approach songwriting as a meaningful enterprise and progressed to become one of the most prolific pop/rock bands ever. Thirteen splendiferous albums in seven years with many more singles that never made it onto an album is a remarkable achievement.

You might have noticed by my choice of songs above, I am particularly enamoured with ‘The White Album’. This was always the one that stuck out for me with its sheer breadth and scale of differing ideas – melodic, harmonic and lyrical.

The most common argument against ‘The White Album’ is that it lacks focus due to the divisions taking place between the Fab Four. They were no longer unified and John Lennon later said that ‘The White Album’ was the sound of The Beatles in the midst of divorce.

Many critics argue, if only the band united they would have discarded lesser songs such as Piggies and Why Don’t We Do It In The Road in favour of the best fourteen songs on a single album (rather than the thirty songs and double album that it became).

But in the Companion Ian Inglis argues that ‘The White Album’ was popular music’s first post-modern album. Polarity and divisiveness, he writes, forged new conceptions of what the rock album could achieve.

The slogan of post-modernism is that there are no longer any certainties. That is the one certainty. The grand-narratives that once constructed (and constricted) our vision of the world have cracked and splintered. ‘The White Album’, reckons Inglis, was a very successful attempt to deconstruct the grand-narrative that The Beatles had built up around them since 1963.

They did so by employing strategies such as bricolage, fragmentation, pastiche, parody, reflexivity, plurality, irony, exaggeration, anti-representation and meta-art. All this, according to Inglis, fashioned “a contemporary text whose music(s) described the present, recalled the past, and anticipated the future”.

Nevertheless, George Harrison did say that “There was a lot of ego in the band [when recording ‘The White Album’], and there were a lot of songs that maybe should have been elbowed”.

Gary Burns argues that The Beatles are foundational members of the sociological canon of rock music – rock music as a social phenomenon – and that they embody the political and ideological shifts that took place in the 1960s.

Anthony DeCurtis argues in his foreword that the story of The Beatles “has the arc of a fairytale with a heartbreaking ending”.

The death of John Lennon in 1980 becomes, naturally enough, an important focal point of the book. Many of the contributors note Paul McCartney’s delusion with the mythic status acquired to Lennon after his death (‘Saint John’), a narrative that often blamed McCartney for breaking up The Beatles.

Lennon’s death came at a time when Republicans came to power in the US, spearheaded by the neo-liberalism of Ronald Reagan. Michael Frontani argues here that the reason for such mass adoration and public sympathy for Lennon was not so much to do with his violent and tragic end, but because his death signalled the end of progressive social change in America.

Lennon was always the most vocal opponent of the status quo, especially in relation to politics (for Harrison, it was spirituality). It would be interesting to know what Lennon would have made of Obama’s healthcare reform.

Some essays in this volume lack critical analysis and fall within the bracket of summary. Much of the same stories are repeated and the contributors’ obvious love for The Beatles sometimes borders on the sycophantic – but hey, you can’t blame someone for liking The Beatles too much and if you are interested in the 1960s and The Beatles, you will enjoy this book.

The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles

Edited by Kenneth Womack

pp320; hardback. Price: €63.25 ISBN: 9780521869652

Paperback price: €18.39 ISBN: 9780521689762

Cambridge University Press