Elementary, Mr. Coelho

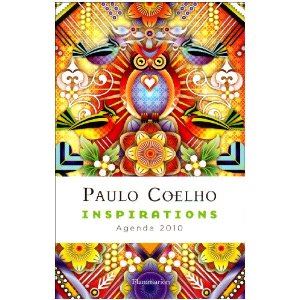

It was the Greek Philosopher Empedocles who, in the 5th Century BC, proposed a theory of reality based on the four natural elements. He believed that all things were a combination of water, earth, air and fire and held that the entire universe could be understood only as a limitless conglomeration of these basic elements. Fast-forward 25 centuries and Paulo Coelho, one of the all-time best-selling novelists and the spiritual guru of millions, has used this elemental theory as the foundation for Inspirations, his second spicy anthology of favourite extracts from world literature.

Coelho sees this method of organising his new anthology as not merely convenient but deeply symbolic. As he explains, “the four elements symbolize both our world in all its dimensions and the way we dwell in the world, the way we see it.” Coelho considers an anthology to be “a gift, something we arrange according to our sensitivities, to give to others.” Like wild flowers, Coelho sees great books as having delicate scents, but he fears that in bringing together these blooms they may lose their unique perfumes.

For this reason Inspirations is a select choice of complementary texts which make up “a sort of natural cathedral that aims at stirring the soul.” With the garden of all time and space to gather flowers in, Coelho’s task is not easy. Initially his choices seem curious, even bizarre, but a pattern soon emerges. For example, ‘Water’ starts with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Ugly Duckling. Next we are transported to Arabia by one of the Tales from the Thousand and One Nights. We then listen to the ironic words of Niccolo Machiavelli taken from The Prince. Without further ado we join Alice at the court of the White King and Queen for a recital of Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poem Jabberwocky. Lastly, we receive tutelage in the Art of War from Sun-Tzu.

This mixing of the mythic and modern, sacred and profane, is Coelho’s mode of operating in Inspirations. When he turns to ‘Earth’ it is Irish writers who predominate. A choice passage from Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis is followed by Bram Stoker’s ghoulishly gothic account of the lunatic Renfield’s demented attempt to eat his way from one end of the food chain to the other in Dracula. Two of W.B. Yeats finest poems, He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven and The Song of Wandering Aengus, are also included. In between there is a typically juicy extract from D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Hannah Arendt’s awesome meditation on the banality of evil from Eichmann and the Holocaust.

‘Air’ brings together another unlikely assembly. What fascinates about this section is observing how the same questions resonate in different extracts. Nelson Mandela’s eloquent defence of the inviolable dignity of the individual from his 1962 trial gains new significance when placed alongside George Orwell’s terrifying account of a society without freedom, obsessed with power and driven by hate in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The concept of identity emerges anew when Jorge Luis Borges The Library of Babel, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde are brought together.

In ‘Fire’ Coelho really rolls out the heavyweights. Extracts from the Rig Veda, Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet and the Bagavad Gita are followed by a poem by the Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore and wise sayings from The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Desert Fathers. What surprises here is that, despite the great diversity of cultures and faiths represented, all of these texts deliver messages of hope and enlightenment in an identical, profoundly simple way. As a whole Inspirations leads the reader to feel the same things over and again in countless different ages and settings. We are no less captivated by the strength and beauty of Princess Sharazad and Marquez’s Remedios than we are by Leopold Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs or Orwell’s Julia. Our revulsion at the inhumanity of Eichmann, Mandela’s oppressors and Wilde’s jailors is the same that we feel when faced with the monstrousness of Mr. Hyde, Victor Frankenstein and Winston Smith’s nemesis, O’Brien.

Coelho’s capacity to find parallels between such a rich variety of traditions, to bind together the hearts and minds of his readers with a common thread, is a prime indicator of the gift that has allowed him to become one of the most popular of contemporary storytellers. His luxurious, incandescent prose has the quality of mental honey, and its has never been less difficult to see why a work like The Alchemist has sold 65 million copies and been translated into a record 69 languages. By setting these texts side by side Coelho encourages us to look for common themes and universal messages. Consequently, Inspirations is like a map of civilization that allows us to follow where we have come from and chart where we will go. It reveals the cyclical nature of human actions, and shows us how compassion, understanding and love are the only values that allow us to make sense of life.

Elementary, Mr. Coelho.

Elementary, Mr. Coelho.