Comrades in arms

Journalist James Brabazon's recollections of his exploits in the war zones of Africa in the company of the infamous mercenary Nick du Toit make for some exciting if occasionally gut-wrenching reading. By Edward O'Hare.

James Brabazon should be dead. In his ten years as a war correspondent he has seen more carnage than most of his colleagues ever will. A man with an unquenchable thirst for danger, he was the only western journalist to report on one of the most violent episodes in recent African history, the civil war in Liberia. This led to his involvement with one of the world's most infamous mercenaries, Nick du Toit. In My Friend the Mercenary Brabazon records his unlikely friendship with du Toit from their introduction in April 2002 up until the crazed, frantic days that preceded the failed plot to overthrow the government of Equatorial Guinea in March 2004.

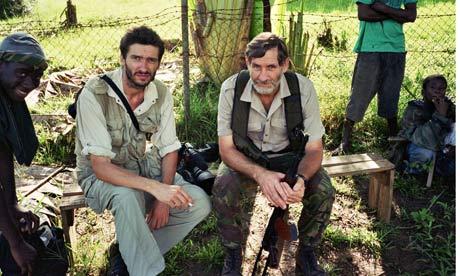

(Picture: James Brabazon with Nick du Toit)

To say that James Brabazon is an impulsive character would be a massive understatement. He had scarcely left Cambridge when he journeyed to Kosovo, Afghanistan, Palestine and Zimbabwe, working as a photojournalist, before ending up in Sierra Leone. Here he conceived a documentary on the then unreported conflict in Liberia, even though he knew virtually nothing about the country. He therefore needed the help of someone familiar with the territory, an experienced old hand who would hold the mission together even in the most deadly situations.

Nick du Toit had begun his career in the South African Army, ultimately becoming one of the Recces, the apartheid government's notorious equivalent of the SAS. As part of this special forces unit, du Toit earned the unusual reputation of being both a highly skilled medic and a consummate professional killer. This led him to become recruited by Executive Outcomes, the private South African-run army which became the most sought after and profitable mercenary service in modern times.

On foot of du Toit's agreement to be Brabazon's guide and bodyguard, a team was quickly assembled and flown into Guinea. But Liberia was not a wise place for a novice journalist, an inexperienced television crew and a wanted criminal to find themselves. By May 2002 the country was in a state of absolute confusion. The Liberian President Charles Taylor was reputedly trying to crush a band of rebels calling themselves LURD (Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy) but when Brabazon and du Toit arrived even the United Nations knew nothing about them for certain.

Bribing everyone in sight, Brabazon and du Toit secured safe passage into rebel territory. Like any war reporter, Brabazon knew that he would have to capture real fighting on camera if his film was to get picked up. As it turned out, there was to be no shortage of this. In retrospect Brabazon was hopelessly unprepared for his undertaking. Even though he had already experienced war, what was unfolding in Liberia was often closer to genocide. The LURD forces, made up mostly of AK-47 waving teenagers, were engaged in committing bloody attacks on Taylor's strongholds. Civilians caught up in these were shown no mercy and prisoners were horrifically tortured before being barbarically put to death. Desperately trying to hold on to his sanity, Brabazon found himself recording unbelievable acts of viciousness and cruelty.

Struck down by serious illness, Brabazon and du Toit nursed each other and barely made it out of Liberia alive. It therefore came as a shock to him when, a few weeks later, he and Nick found themselves back in the country. An American news network, intrigued by what Brabazon had filmed, financed a second trip and at last Brabazon completed his task. Brabazon and du Toit next caught up in Paris, after Nick told him that he was meeting a rather special old friend about another African adventure and thought James should be in on the act. The 'old friend' turned out to be Simon Mann, the arms dealer and head of Executive outcomes and the 'African adventure' was the Equatorial Guinea coup.

Brabazon left the meeting with Du Toit and Mann convinced he had just been interviewed for a role in the coup but a couple of months later he was astonished to hear that Mann, along with 64 other mercenaries and ten tonnes of weaponry, had been intercepted at Harare airport while Nick du Toit was arrested in Equatorial Guinea and detained in its dreaded Black Beach prison. The plot, described by one commentator as "an astonishing catalogue of buffoonery" had been financed by a Lebanese oil tycoon and involved the ousting of President Obiang and the installation of Severo Moto, a pretender living in exile in Spain and a puppet controlled by the conspirators. After months spent investigating the coup, Brabazon now believes that the audacious scheme had the backing of several senior ranking British politicians and businessmen (most famously Mark Thatcher), US intelligence and the Spanish authorities and it's his theory that he was betrayed by a double agent who was working for both Mann and the South African government, which had decided to support Obiang for its own gain.

My Friend the Mercenary is a compelling read. A factual book which contains more hair's breadth escapes and edge-of-your seat action than most thrillers, it grabs you with both hands and rarely lets go. Its main problem is Brabazon himself. Clearly someone who believes himself born to the role of the globetrotting, world-weary journalist, he writes in a boastful, seen-it-all manner which can be tiresome and very off-putting. He fills the narrative with too many details about his personal life, something that clouds the complex picture of espionage and corruption he is trying to build. Nonetheless, My Friend the Mercenary is an interesting exploration of contemporary geopolitics and of the ethics of journalistic practise.

My Friend the Mercenary by James Brabazon

Canongatepp 457

EURO 20