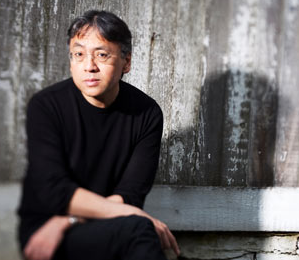

Cloning and beyond in Kazuo Ishiguro

The release of the film adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro's bestselling novel Never Let Me Go (2005), and the current reissue of the novel itself, makes it timely to consider the moral questions raised by cloning. By Joseph Mahon.

The novel describes a post-war society whose scientists have been commissioned to furnish a supply of cloned human beings to be used as life-saving organ generators for the rest of the population. The clones who feature in the novel have a pleasing childhood and adolescence at a remote rural boarding school called Hailsham, in England. But as young adults they become 'donors,' persons whose organs are removed, in hospitals, for transplantation into other needy uncloned human beings. Some are appointed 'carers' of those who 'donate,' until they themselves become donors in turn. Each clone will typically make several donations until he or she 'completes.' Completion is a euphemism for death.

The biography of these clones is described as follows:

"None of you will go to America, none of you will be film stars. And none of you will be working in supermarkets as I heard some of you planning the other day. Your lives are set out for you. You'll become adults, then before you're old, before you're even middle-aged, you'll start to donate your vital organs. That's what each of you was created to do. You're not like the actors you watch on your videos, you're not even like me. You were brought into this world for a purpose, and your futures, all of them, have been decided."

A clone is an individual which is genetically identical to another individual from whom it has been reproduced or created. This is done by a process known as nuclear transfer. Here a body cell, such as a skin cell, is removed from the individual to be cloned, and its nucleus is removed. An egg cell, or oocyte, is extracted from the ovaries of a woman, and its nucleus is destroyed. The nucleus from the original body cell is injected into the egg cell whose own nucleus has been removed, and this same egg cell is stimulated with electricity or chemicals to make it act as though it had been fertilised naturally. The resulting embryo is implanted into a womb where gestation continues as normal. The child will contain genes from the donor parent only (the individual who supplied the body cell), and so will be a copy of that person.

Most moral philosophers and bench scientists find it easy to justify the use of cloned human embryos for the purposes of research, and as a source of stem cells in the ongoing battle against the killer diseases. They reason that a human embryo is not a human being, that it is merely a life-saving tissue generator and, as such, does not have the rights of a human being. Ishiguro's novel challenges this argument in the following two ways:

[1] If it is morally permissible to use, and destroy, cloned human embryos for medical purposes, then what objection can there be to using these same entities at a later stage of development for the same medical purposes?

[2] If the circle of respect does not extend to cloned human embryos because they are cloned, then logically it doesn't extend to any cloned individual, whether it be an embryo, an adolescent, or an adult.

Ishiguro's novel argues that it is wrong to use cloned human beings as life-saving organ generators, because they are human beings the same as us. The case is made by Miss Emily, one of their 'guardians' at Hailsham. The guardians had insisted on calling them 'students.' They had encouraged their art work, and then sequestered it for safe keeping. They had done so "because we thought it would reveal your souls. Or to put it more finely, we did it to prove you had souls at all." It had been necessary to do "because it wasn't something commonly held when we first set out those years ago."

The teachers at Hailsham had led a small counter-cultural movement dedicated to the proposition that clones are properly human, and are entitled to the same respect as everyone else. Their movement had enjoyed a limited success. "We demonstrated to the world that if students [clones] were reared in humane, cultivated environments, it was possible for them to become as sensitive and intelligent as any ordinary human being. Before that, all clones - or students, as we preferred to call you - existed only to supply medical science.'"

Are Ishiguro's clones as human as the rest of us? They seem to be.

They are curious, playful, academic, caring, and artistic; they are sometimes angry, sometimes horny, and sometimes sad. They are also gullible, complacent, timid, fatalistic and conformist. They are apolitical and remote, moving through the surrounding communities and countryside when they leave school without seriously interacting or engaging with other civilians. They sometimes question, remonstrate, and wonder, but it never occurs to them to rebel. They have a limited moral awareness: they care for each other, and are heroically willing to sacrifice their vital organs to help others survive, but they seem to have no realisation that they are being treated badly and unjustly themselves.

From this perspective, Ishiguro's novel is less an argument against the use of clones, in medicine, for their body parts, and more a parable that cautions against an education system and an upbringing which instils conformity, complacency, and a limited moral awareness.

Ishiguro's post-war society justified its maltreatment of the clones on the basis that they were somehow less than human, and that harming them mattered less than helping others. One of the key passages in the novel explains this thinking as follows: "However uncomfortable people were about your existence, their overwhelming concern was that their own children, their spouses, their parents, their friends, did not die from cancer, motor neurone disease, heart disease. So for a long time you were kept in the shadows, and people did their best not to think about you. And if they did, they tried to convince themselves that you weren't really like us. That you were less than human, so it didn't matter."

Being considered "somehow less than human" is merely a new spin on the Nazi idea of life not worthy of life. In this way, Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, like Camus' The Plague, is an allegorical novel about evil and the need to resist it. It is a chilling reminder of the dangers inherent in narrowing the circle of respect. Auschwitz did not exhaust our talent for evil; we just move on to another batch of victims.

Bring on the clones!

Joseph Mahon teaches at the School of Humanities, National University of Ireland, Galway