The choices around cutting child benefit

If we see universal child benefit being systematically dismantled in the next Budget, while we retain tax breaks that massively benefit people with the highest incomes, then the fundamental values underpinning Ireland's budgetary policy need to be questioned. By Nat O'Connor.

Despite the helpful reminder from Joseph Stiglitz that "Austerity has almost never worked", the Government has decided to cut further and deeper in the next Budget, with reports that Minister Noonan will again prefer two-thirds spending cuts combined with one third tax increases.

There are no easy choices left for the Government, as it seeks to close the deficit through €3.5 billion of measures. While it is necessary to close the deficit, there are a couple of significant questions to be asked that provide important context for any consideration of cutting child benefit.

First of all, what is the Government's end goal in terms of public versus private provision of vital matters like health and education, childcare and housing, pensions and income?

Secondly, if 'everything' (including child benefit) is on the table for discussion, what are the values and principles that will guide the decisions about what to cut and who to tax?

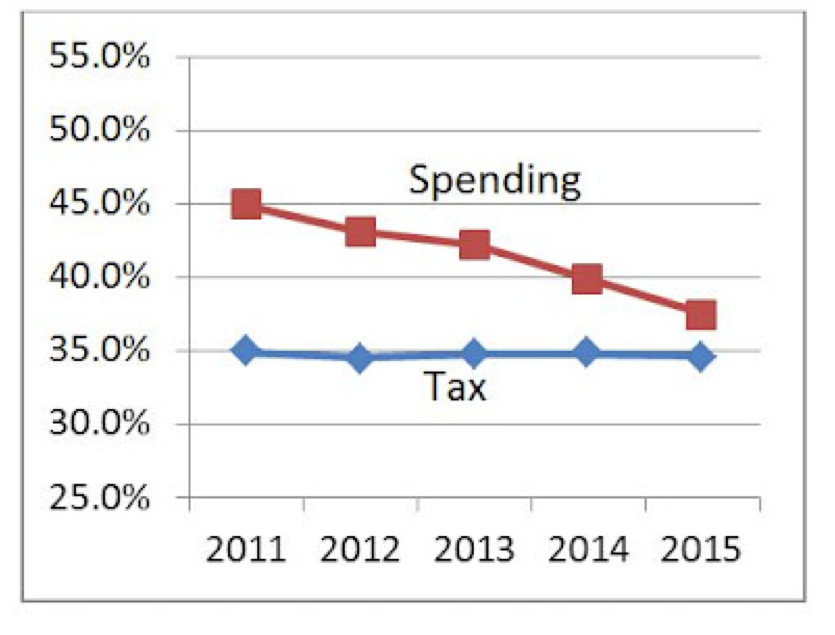

As this chart shows, the net result of budgets to date has been to 'flatline' Ireland's overall level of taxation while reducing public spending. Any talk of a 'balance' between tax measures and spending in the actual effect of recent budgets is simply not true.

As this chart shows, the net result of budgets to date has been to 'flatline' Ireland's overall level of taxation while reducing public spending. Any talk of a 'balance' between tax measures and spending in the actual effect of recent budgets is simply not true.

The figures are based on the Government's plan (in Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Budget 2012, page D.19) to end up with total revenue of 34.6% of GDP and total public expenditure of 37.5 % of GDP by 2015. While these figures might be slightly different in Budget 2013's documentation, there is little evidence of a changed strategy by Minister Noonan.

What level of public services can be delivered through spending at around 37.5% of GDP?

The answer is, not anything like as much as what was delivered at the height of the boom and not the same kind of 'welfare state' as most Western European countries. The long-term EU27 average level of spending is roughly ten percentage points higher than Ireland. As such, if the Government chooses such a low target level of public spending, it should come as no surprise that some core elements of the 'social contract' between Ireland's State and its citizens are now being questioned.

One of those core elements is universal child benefit. There are three clear features of this payment, which indicate fundamental values and principles: (1) It goes to all children equally; (2) It is paid to all citizens with children regardless of their income, as part of the 'return on investment' of taxation and social insurance; and (3) It is a payment from everyone to Ireland's children, regardless of whether or not they have children of their own.

Universal child benefit should not be considered a 'sacred cow' any more than the 12.5% corporate tax rate or the existence of the Senate. However, these are major building blocks of the Irish social contract and they should not be radically changed without serious discussion of the implications.

Instead of an open discussion on the issue, there is a risk that the guiding principles underpinning universal child benefit are being discarded without adequate discussion of the changed nature of Ireland's welfare state and social contract that is implied by those changes.

For example, there are endless reports that wealthy people don't need child benefit and should not get it. Somehow it is taken as the 'obvious' and 'easy' solution to means test child benefit or to tax it. However, this argument sweeps aside all three guiding principles. Universal child benefit is a social contract, not an individual contract between a person and the State. It is only from an individualistic perspective that it makes sense to say Person A is too rich, therefore tax or cut his/her child benefit.

In reality, the administrative burden involved in means testing, plus the highly contentious issue of deciding who needs it and who can't have it, is expensive and fraught with difficulties. A much simpler solution is to say that, if some wealthy people don't need child benefit, than simply increase general taxes on wealthy people. At the end of the day, we all benefit from Ireland's children - they are the future tax payers, health workers and others that we will need when we are old (whether or not we have children ourselves).

However, if we decide that universal child benefit in its current form is too expensive (because of the decision by Government to target public spending at 37.5% of GDP) than it is possible to imagine alternative uses of public money that would uphold the values and principles of the welfare state.

For example, if we decided that the provision of municipal crèches and pre-school education was a pressing social need (which it is) then we could provide places free-of-charge, to all children equally, regardless of their parents' means and paid for by everyone; because we will all benefit from all children in Ireland having a better start in life and better educational development.

For example, the OECD advises on the benefits of spending early on children.

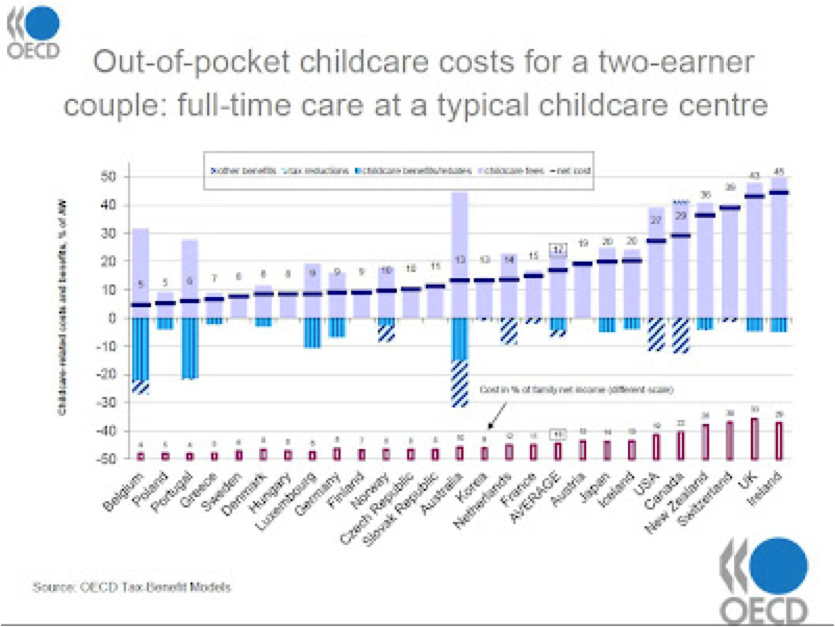

This chart from another OECD presentation shows that Ireland (in 2008) had the highest net childcare costs in the OECD. No wonder so many families rely on child benefit payments!

What is so rarely mentioned in Ireland is that when taxes are low, people end up paying privately out of their own pockets. It can be cheaper to pay more tax or social insurance to purchase certain kinds of goods and services collectively. And of course, when we pay collectively, we all share the cost of our children from whose future contributions we will all benefit. When we pay privately, the burden of paying individually is placed squarely on the shoulders of young families, who are not the best placed to carry that burden.

If we see universal child benefit being systematically dismantled in the next Budget (as is suggested in recent reports), while we retain tax breaks, such as those for private pensions that massively benefit people with the highest incomes, then the fundamental values underpinning Ireland's budgetary policy need to be questioned.

The next three or four Budgets are not just about closing the deficit, they are about the nature of the future relationship and social contract between citizens and the State in Ireland for decades to come.

Originally published on Progressive-Economy@TASC. Republished with permission.

Image top: What What.