A burst of conversation

Communication between people happens in bursts, with long periods of conversation and also long periods of inactivity, according to the findings of a major research collaboration in Spain, writes John Holden.

A massive research project into communications habits, which was carried out by researchers at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (UC3M) in conjunction with Spanish mobile giants Telefónica, has just been completed. The yearlong study, which analysed 9 billion phone calls, has found that people’s communication habits tend to happen in “bursts” followed by long periods of inactivity.

This is the first time phone conversation habits have been quantified and analysed on this large a scale and its results may be of use in many areas, from business and marketing to psychology, sociology and social policy transmission.

The study, entitled ‘Dynamical strength of social ties in information spreading’, was recently published in the journal Physical Review E. It suggests that human behaviour - in communication and in other habits - doesn’t happen homogeneously over time. Instead there is no communication, followed by short intervals or “bursts” of intense communication.

As previously stated, the relevance of the research has several uses including in business – in terms of how commercial information is diffused and in as well as analysing viral marketing trends - but also for sociologists and psychologists looking at how rumours are spread, opinions and social and governmental policies.

“This aspect of human activity which has also been observed in other activities such as e-mail, web page visits and stock market operations governs communication between people,” explains co-author of the study, Professor Esteban Moro from the Interdisciplinary Research Group of Complex Systems at the Mathematics Department in UC3M.

Another aspect of the research investigated group conversations. While their conclusions found that group communication also happened in “bursts”, these surges of conversation tended to happen at the same time among the members of the social group, which led to increased acceleration of information diffusion within that group.

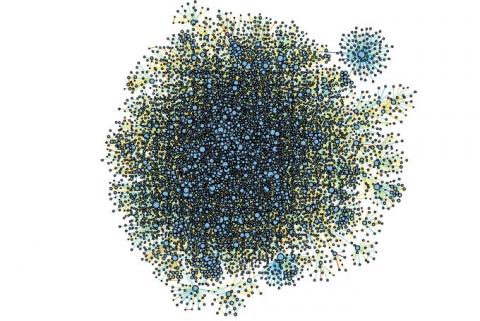

Ultimately the aim of the research is to learn when, how much and with whom people communicate. While this may sound a little too much like Big Brother for some, the aims of the study, according to the researchers involved, are in no way nefarious. The scientists at UC3M conducted the study with two purposes in mind, they say: “The first being, to see if relations in a social network can be quantified better, that is, determine if the communication rhythm between two persons allows us to know something about the ‘strength’ or characteristics of the relation (family member, acquaintance, friend, colleague, etc.); and the second, to investigate the impact of these rhythms on the propagation of information in social networks, in processes such as viral marketing, product recommendations, etc.”

Telefónica gave access to anonymous databases of calls in an unspecified country during an eleven month period. The researchers analysed around 9,000 million calls between 20 million people. "This large volume of data and the extended time period guarantees the representativeness and universality in the results", says out another one of the study’s author, Giovanna Miritello, a PhD candidate in the Mathematics Department of UC3M.