Blood, stones, and you

Between wage stagnation, tax increases, and debt, the prospect of kicking growth into the economy via consumer demand is likely to disappoint. By Michael Taft.

For households in work, if they manage to hang on to their jobs, it is going to be a difficult few years ahead if the projections for wage increases is anything to go by. This is something rarely referred to when Government or independent forecasters produce their numbers. In some ways this is understandable – there are so many other numbers to examine: GDP growth, unemployment, emigration, etc. But looking at wage increases can give us another perspective on future prospects – and those prospects don’t look terribly upbeat.

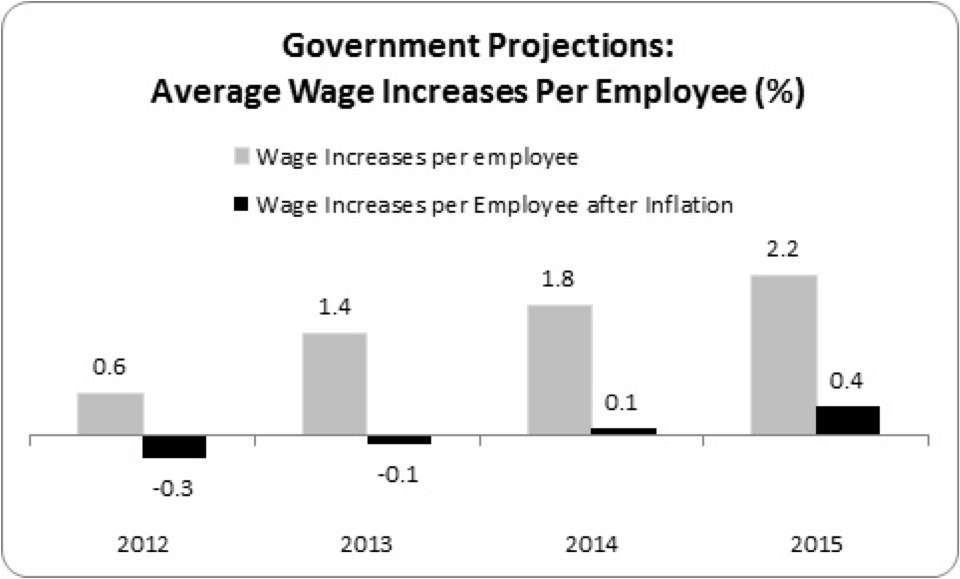

Back in April, the Government projected average wage increases per employee.

As seen, nominal wages are expected to rise by about half-a-percent next year and increasing until it exceeds 2% by 2015. Ok, not great, says you, but given that wages are expected to flatline this year, it’s better than nothing.

However, when we take inflation into account (using the government projection of the EU’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices, which excludes mortgage payments), we find a more worrying trend. Average real wages will be cut next year, flatlining in 2013/14. Even by 2015, real wage increases will struggle to climb a half-a-percent.

Of course, by the time the Government publishes its next set of projections – probably in October with its new four-year fiscal targets – these percentages will probably fall. All forecasters have been busily revising downwards their estimates from last spring and summer; the Government has indicated they will do the same. And usually lower GNP and employment figures translate into lower wage increases.

None of this takes account of taxation. The Government has given a commitment not to increase income tax - which I’m going to assume means freezing rates, personal credits and the standard rate tax band. However, even this will degrade real incomes, for freezing rates, credits and tax bands means the government increases its take through inflation.

Let’s take two single workers – one on average industrial pay and the other on low-pay. Both will suffer a real pay cut of 1.1% each from a combination of projected pay cuts and inflation. So even by doing nothing (not inflation-indexing tax credits and the standard rate tax band), workers will, on average, experience a real pay cut of about €5 to €6 a week.

If the Government proceed with any non-income tax increase (they’ve already signalled a Household Charge) then things will degrade that bit more. For those on low wages, they will experience another 0.5% percent fall in take-home pay.

In real life it won’t play out like these averages. Many will get pay increases – in particular, those in the multinational sector. Others will find their wages falling by a greater amount. Most will probably see their pay frozen (e.g. the public sector). So the picture will be varied. But, on average, that’s what we’re facing into.

The situation is similar for social welfare recipients: if their rates are frozen, they will suffer a real income cut of nearly 1%. If the Government goes after rent supplement or other income supports, that cut will deepen.

With real wages flatlining for some years to come, with tax increases, with households still deleveraging - whether it’s mortgages, credit card debt or door-stepping loan sharks – the prospect of kicking growth into the economy via consumer demand is likely to disappoint. Which is why the Government is projecting the domestic-demand recession to continue into next year.

You might think it is difficult to get blood from a stone. But that’s what the Government will be attempting to do – even if they avoid the headline rate cuts in taxation or social welfare.

The only problem is that if they squeeze too much, the rocks will crumble.

{jathumbnailoff}

Image top: kr428.