The biological evolution of economic problems?

Do rich kids go to college more often than poor kids because they’re rich? Or are there personality, genetic and environmental issues at play? A groundbreaking new research project at the UCD Geary Institute attempts to tackle large socio-economic questions through an inter-disciplinary approach that will draw in expertise from economics, biology, neuroscience and psychology. By John Holden.

At a government level, tackling educational disadvantage has always been “solved” by throwing money at the problem through grants and scholarships. But research suggests there are greater forces at play than simply just money.

“Traditionally, going back over 50 years of research, economics has approached big policy questions such as educational decision-making in a way which only gave us partial answers, and we then built our economic models around those datasets,” explains Colm Harmon of the UCD Geary Institute. “We have had data available on what people earn and how much education they have achieved over their lives for decades. Coupled with computer power, there has been an explosion of this type of data analysis.

“The tricky bit was that there was a lot of unexplainable stuff,” he says. “We had very little to say around how people’s personality differences, genetic issues and the environment we grow up in affects our decision-making.”

With the leadership of Nobel-prize winning economist, Professor James Heckman of the University of Chicago, the UCD Geary Institute has secured funding of 2.5 million euro from the European Research Council which will take “an integrated developmental approach to health that studies the origins and the evolution of health inequalities over the life course and across generations, and the role played by cognition, personality, genes, and environments.” The project will look at both health and educational inequalities from a broader perspective than the traditional socioeconomic approach.

In essence, Harmon and his team are trying to assess the biological evolution of societal problems. In the UCD Geary Institute they have been looking at educational inequality for some time. “We have been tracking students here in UCD for the last four years,” he says. “We see a big difference in entry level grades between wealthier and poorer students. There is a pronounced socioeconomic difference. Students from wealthier backgrounds usually enter with much higher grades than students from disadvantaged backgrounds. But four years down the line at graduation you don’t see much difference in grades at all. What you do see, however, is varying perceptions of the future – disadvantaged students will be more pessimistic about where they’ll end up working and how much they’ll be earning.

“Basically we need to change the way people value their own futures,” he adds. “Psychological research has taught us that some people’s personalities are very future orientated while others live very much in the now. Disadvantaged kids at around age 16 are right at the margin of making the decision to stay in school, get a job, get involved in crime etc. And they tend to be very orientated in the now. Therefore the opportunity offered by economists to stay in school and do the right thing seems daft.

“It teaches us that the conventional way to approach the problem – i.e. we’ll give you a grant so you can go to college – isn’t working.

“When I was in school in Ballyfermot 20 years ago, three students from my year went to college. 20 years later little has changed. This suggests issues other than money are at play - peer effects, what you’ve learned about your future, sense of expectation - those kinds of factors.

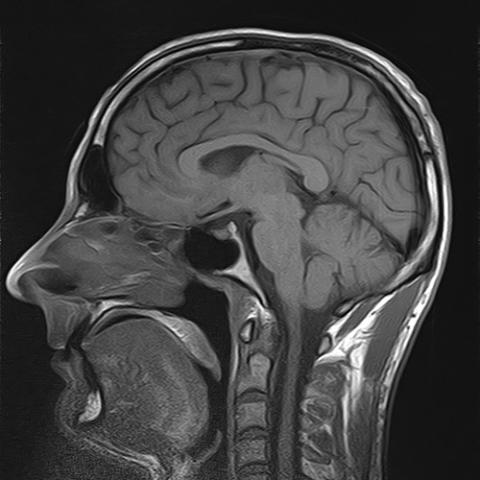

This is where the economist requires the expertise of the scientist. “Measurements of infant development of vocabulary show that there is little difference between how quickly rich and poor infants start forming words up to about 15 months,” says Geary. “But then a threefold gap starts to open up by around 36 months.

“Such disparities open up very early and then persist over the lifetime. And it gets harder and harder to intervene to close those gaps. Biologists will tell you that brain wiring becomes formed. So you find yourself with a 16-year-old who has fallen behind and is disillusioned with education. All government think to do is to throw money at them.”

This project will run over five years and will include national and European analysis. “The funding will support a team of eight PhD and post doctoral students working flat out for the next five years,” says Harmon. It’s not easy to get this funding. 90% of applications are rejected.”

Image top: Ben Beiske.