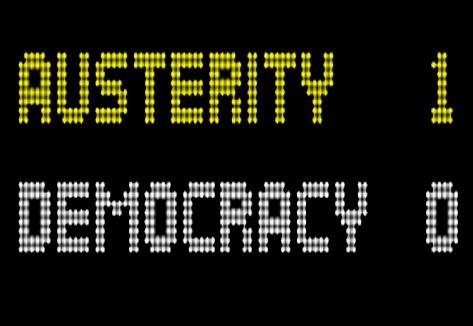

We need a referendum on this undemocratic Austerity Treaty

The timeframe to build significant political pressure to force them to hold a referendum is short, but it needs to be done. By Paul Murphy.

Leo Varadkar’s comments about referendums being undemocratic raises a question about the government’s understanding of democracy. Presumably getting elected on the basis of not giving “another red cent” to the Anglo bondholders - and then proceeding to hand over billions to them - is more democratic than allowing the people to decide on a vital question like joining an Austerity Club.

The fact that the Government is striving might and main to avoid a referendum on this treaty adds insult to injury because the treaty itself involves a fundamental attack on basic democratic rights. The Government is eager to avoid debate on this, with Varadkar complaining about extraneous issues being dragged into a referendum debate for example. However, it is the Left that has attempted to debate the content and meaning of the actual treaty so far, which the government has studiously avoided. We want to have that debate in front of the mass of people and for the people to decide whether we sign up to this treaty.

A key argument against us joining the Austerity Club this treaty will create is that it means signing up to permanent austerity across Europe. This will be disastrous for working people and economies across the continent. Michael Taft has outlined the consequences in terms of extra “adjustments” to our budget in signing up to the “balanced budget” rule, and he estimates these at €5.7 billion if the European Commission insists that we meet the 0.5% structural deficit target by 2015. I will return in a later article to the details of how austerity is enshrined in this treaty and what it will mean. Here, I want to focus on the crucial question of democracy, which is significantly undermined by this treaty, precisely in order to facilitate the imposition of that austerity.

The first thing to acknowledge is that the capitalist society we live in is very far from being truly democratic. As the Occupy protestors pointed out, our society and economy is run for the 1%, not the 99%. The power of the 1% flows from their ownership of the key resources and sectors of the economy and the holding of political power by establishment parties that are funded by big business and serve their interests. We have a parliamentary capitalist democracy, with all of the limitations that electing people once every five years in elections dominated by big business funding involves and with the vital decisions about our economy made in the boardrooms of big business and on the stock exchanges. At a European level, there is not even a parliamentary democracy, and real power lies with the unelected European Commission and the European Council.

However, the limited democracy that does exist is being undermined over the course of this crisis. The European Central Bank sent a detailed prescription of austerity measures to the Italian government for them to carry out. The so-called six pack on economic governance shifted important powers from elected governments to the unelected European Commission and made changes to how voting is carried out in the European Council to make punitive sanctions for violating neoliberal diktats semi-automatic. This treaty takes this process even further and is a significant attack on the basic democratic right to elect a government to decide on budgetary and economic strategy. It does this in two key ways.

Firstly, with the balanced budget rule it effectively ties future governments to the same economic policies as this one – neoliberalism and austerity. In the words of Martin Callanan, the leader of the Conservatives in the European Parliament, “We are making socialism illegal.” It rules out governments running structural deficits – which could be used for investment in vital public works, to engage in necessary public spending and so on. It is surely one of the most basic requirements of a democracy that people are free to vote for different economic policies. This is reminiscent of the old Mercedes phrase – “any colour you want as long as it’s black”, now you can have “any government you want as long as it’s neoliberal”.

This has not come out of the blue – it is part of a process whereby economic policy has been technocratised. There has been a conscious attempt to use the crisis (a crisis of capitalism caused by speculators, bankers, neoliberalism and deregulation, let us remember) to move economic policy out of the sphere of democratic discussion and to turn it into a purely technical question. So neoliberalism is not posed as a policy choice, it is simply ‘responsible’ behaviour. This is the excuse for the removal of elected governments in Italy and Greece and their replacement by governments of bankers.

Incidentally, this removal of an elected government’s right to determine its economic policy may well be unconstitutional as well as undemocratic. The reason for that is that the Irish Constitution explicitly states that it is the in government’s power to determine the budget (Article 28.4.4) and also that that power cannot be alienated from it (Article 6). If the treaty’s proposals are carried, the power of a government to determine the budget will be extremely limited.

The second key proposal diminishing democracy is the mechanism for countries to be effectively placed in administration. This is contained in Article 5 of the treaty, which says that countries in an “excessive deficit procedure” have to put in place a “budgetary and economic partnership programme including a detailed description of the structural reforms which must be put in place and implemented to ensure an effective and durable correction of their excessive deficits.” These programmes will be endorsed and monitored by the European Commission and Council. In this way there is a surrender of budgetary powers to the Commission and Council; consequently it will not only be countries in receipt of ‘bailout’ funds like Ireland, Greece and Portugal that will have their budgets effectively written by these powers.

The Government will have to be forced, legally or politically, to hold a referendum on this treaty. The timeframe to build significant political pressure to force them to hold a referendum is short. Sign the petition online at www.referendumnow.eu. {jathumbnailoff}

Paul Murphy is Socialist Party and ULA MEP for Dublin.