Role of left in securing Yes vote should not be underestimated

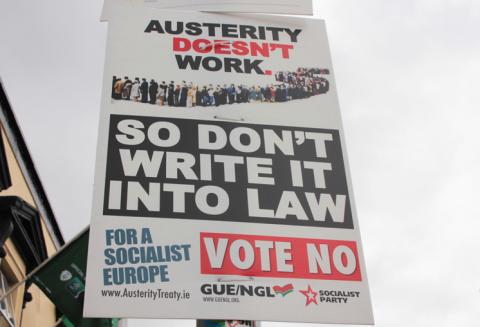

There was a coherent case to be made for the No side in the Fiscal Treaty referendum campaign, but it went unargued. By Vincent Browne.

The role of the left in securing a Yes vote in the referendum should not be underestimated. The scale of their waffle and incoherence contributed substantially to the success of its opponents. The left's failure to deal with the central issue of funding for the Irish state beyond 2013 - with even a smidgen of credibility - was a clincher.

There is not the remotest prospect of the left achieving significant electoral success in the next election or at any time in the near future. So, unhappily, for all those who are apprehensive of the rise of an 'extreme' socialist movement here, they may sleep contentedly: there is no chance, at least on current form.

Sinn Féin is better and more credible, and the performances of Mary Lou McDonald, Pearse Doherty, Pádraig Mac Lochlainn and Peadar Tóibín in the campaign were impressive, even if they also made a mess of the funding question. I exclude them from the left, for Sinn Féin's trajectory is towards domestication.

There was a coherent case to be made for the No side in the campaign, but it went unargued. It was threefold.

First, this was the only opportunity we had to protest against the insistence of the EU that no bank would fail, lest that weaken banks throughout Europe, and its refusal to spread the burden of saving banks throughout Europe.

Secondly, this was the only opportunity we had to protest directly against the imposition of a neoliberal agenda, through permanent supervision of budgetary, economic, labour and competitiveness policies. (By neoliberal, I mean the ideology that says free markets must be the primary instrument of economic and social development - markets driven by demand, not need.)

Thirdly, this was the only opportunity for voters to register their anger at the refusal of Fine Gael and Labour to adhere to their primary election promise: to insist on a debt writedown.

We have since heard from Taoiseach Enda Kenny that this government never sought a debt writedown and never will. Yes, there was a risk on funding, but not a substantial one. But if we and others throughout Europe are silenced by fear, there is no hope.

Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin was by far the most effective proponent of a Yes vote. Kenny wouldn't engage, Labour leader Eamon Gilmore thought the safety of 'the euro in your pocket' was a trump card.

Pat Rabbitte stayed out of it, Joan Burton almost emulated her performance in the general election campaign of February 2011, and Simon Coveney was diligent but, at times, frenetic.

The star of the Fine Gael show was Lucinda Creighton: more confident, more focused than before, and with a bit of lightness.

There was a curious sideshow to the campaign concerning the chairman of the Referendum Commission, Kevin Feeney, a judge of the High Court.

On 3 May, he was asked whether Ireland had a veto on the change to the EU treaties that permitted the establishment of the ESM.

"Ireland could have done that [ie, exercised a veto], but Ireland has already agreed to it by the establishment of the ESM," Feeney said. "The agreement still has to be ratified by the Dáil and Senate."

If Ireland had already agreed to the establishment of the ESM and was now stuck with it, what possible role could the Dáil and Senate have had?

He complicated the issue further with a statement on 18 May, when he said: "It would be possible for Ireland to decide not to ratify the change [despite agreement to the change]. However, the Irish government has announced its intention to have the agreement to the [treaties] ratified by the Oireachtas.

"It is possible that Ireland might still decide not to ratify the change to the [treaties] but whether Ireland would or would not do so is a matter of speculation, given that it is legally possible not to ratify the amendment, but the government has declared its intention to have the amendment ratified by Ireland."

Feeney was a fine barrister and his appointment to the High Court was entirely merited, but this stuff on the veto was all over the place. Ireland certainly had - or has - a veto on the change to the treaties, and that change could not proceed without unanimity among member states of the EU. But it is not clear how ratification to the treaties should be done here.

It seems it does not require a referendum here, for there is no further transfer of powers to the European Union - all the change does is to enable member states to set up a rescue fund if they choose.

Neither is it even clear that the Dáil or Senate have any function on this, for Article 29 of our Constitution states that international treaties do not require ratification by the Dáil unless they involve a charge on the exchequer, which this enabling change does not.

Gerry Hogan, the High Court judge who heard the Sinn Féin application last Tuesday night and delivered an oral judgment last Wednesday morning, acknowledged that the legal issues involved here were very complex, and he withheld an adjudication on them.

Hogan is one of the leading experts in the country on constitutional law, being co-author - with Gerry Whyte of Trinity College Dublin - on the textbook on the Constitution. If Hogan doesn't know, who does?

That aside, we have made our decision on this Fiscal Treaty, so it's onwards and upwards, from here on. Or is it onwards and downwards? {jathumbnailoff}

Image top: Eadaoin O'Sullivan.