The man who would have been Taoiseach

Eamon Gilmore seemed like a viable possibility for Taoiseach, earlier in this two-year election campaign.

He may have brought Labour to record poll numbers, but he's not the closest a Labour leader has ever got to leading the government.

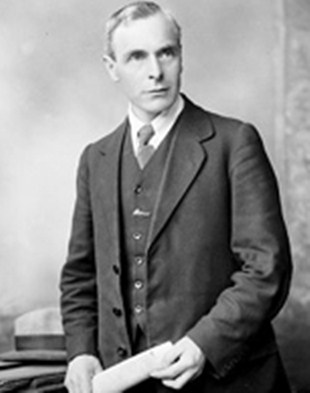

That honour belongs to Thomas Johnson (pictured), leader of the Labour party in the 1920s, who came within one vote of being President of the Executive Council in August 1927 – and that vote was the casting vote of the Ceann Comhairle.

And had an opposition deputy named John Jinks not gone AWOL for the vote, the casting vote would not have been needed, and Labour would have won it.

The June 1927 election saw WT Cosgrave's Cumann na nGaedheal win 46 seats and Éamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil, then still an abstentionist party, win 44 seats. Johnson's Labour won 22. The new National League Party, a coalition of unionists, Anglophiles and anti-Cumann na nGaedheal-ers, won eight seats.

That August, Fianna Fáil decided to enter the Dáil, and promptly supported a vote of no confidence. De Valera agreed to back Thomas Johnson for Taoiseach, promising his support for a minority Labour-National League coalition. On paper, they had the numbers, just about.

The no confidence debate was scheduled for the afternoon of Friday, August 19. William Redmond's National League met at 2pm, and unanimously decided to back the motion, seemingly putting it beyond doubt. (Just in case, Desmond FitzGerald, father of Garret, had risen from his sick bed to attend the vote.)

With the result assumed to be a foregone conclusion, the debate was desultory. "Worse speeches have rarely been heard in Leinster House", reported the Irish Times.

Thomas Johnson's opening statement was "halting and indecisive". There was "no enthusiasm, no applause, hardly any interest; for one felt that everything was cut and dried."

Thomas Johnson's opening statement was "halting and indecisive". There was "no enthusiasm, no applause, hardly any interest; for one felt that everything was cut and dried."

The debate dragged to a close, the motion was put to the house, and a division was called.

"Then comes the astonishing whisper: 'Where is Alderman Jinks?'," recorded the Times.

"Eager eyes scanned the benches for the burly National Leaguer from Sligo. A short time previously he had been in his place...but now he was nowhere to be seen."

"With a sensational turn of the tables, the whole position had been reversed."

With Jinks absent, both sides were level at 71 votes, and the Ceann Comhairle duly voted in favour of the government.

[Pictured: Thomas Johnson]

The government was saved, and the story of the missing Alderman Jinks went around the world, along with rumours that Jinks had been kidnapped. (Given that the Cumann na nGaedheal Minister for Justice, Kevin O'Higgins, had been assassinated the previous month, such rumours weren't entirely incredible.)

"Act of Redmondite saved Cosgrave," headlined the New York Times, and reported that the suspicion that Jinks had been kidnapped had proved false when "Alderman Jinks turned up at his usual haunts and explained that he walked out of the Dail merely because he had changed his mind."

According to the Royal Irish Academy's Dictionary of Irish Biography (see www.ria.ie), the most likely explanation was that Jinks was plied with alcohol by prominent opponents of Fianna Fáil, Major Bryan Cooper (a former unionist MP, then an independent TD) and RM Smyllie (later to be editor of the Irish Times), in a bid to prevent him attending the vote. Jinks's own explanation, records the Dictionary, was that his supporters did not agree with Redmond's policy, but he decided to abstain in order not to split his party.

There was a curious, comical epilogue in the Donegal District Court, the following week, where a man was being prosecuted for possessing a revolver without a permit. The defence counsel claimed his client was ignorant of the existence of the regulations. He should have known about them, insisted the judge. The counsel turned to his client. "Have you heard of Alderman Jinks?" he asked. "No, I have not," said the man.

"There is evidence of the man's innocence," said the counsel, John Tracy. "How can you expect him to know of the existence of these regulations when he does not know of the existence of Alderman Jinks?" There was laughter in the court, but that didn't stop the judge fining the accused £2.

Jinks was defeated in the election that followed, in September 1927, as was Thomas Johnson. Just two National League deputies were returned, and the party went bankrupt the following year. Labour returned with 22 seats. In 1932, it supported the new Fianna Fáil government.

Jinks had a further brush with controversy – and with a casting vote. In 1934, as senior alderman on Sligo corporation, he used his casting vote to vote for himself in a tied mayoral election (according to the DIB). The vote was declared invalid, but Jinks was by then very ill, and he died later that year.

How they voted on the 1927 motion of no confidence:

For the Government

Cumann na nGaedheal 45

Farmers 11

Independents 14

Mr Rice, KC 1

(Rice was a National League member who crossed over for the vote)

TOTAL 71

Against the Government

Labour 21

National League 6

Fianna Fail 43

Mr Belton 1

TOTAL 71