Irish inertia no match for Greek resistance

Greek anger contrasts with our own abject apathy. By Vincent Browne.

Following graphic television reports of the demonstrations in Athens last week, the first question an RTE presenter asked was about the financial markets’ reaction to the demonstrations.

The question was not why the Greeks were so angry over what was happening. Why are they saying on the streets of Greece: ‘‘We are not like Ireland’’ (meaning: ‘‘We won’t lie down in the face of the demands of the financial markets, as the people of Ireland did’’)?

When reports came in about bank workers being caught inside a bank that had been set on fire by demonstrators, and that three of the workers had died in the fire, how is it that nobody asked: ‘‘Why did the bank workers not leave the bank once it caught fire? And, incidentally, what were they doing in the bank during a national strike?”

Why was there no report that bank workers had denounced the bank for preventing workers from participating in the strike, and that there was trenchant criticism of the bank and its owner for neglecting fire and security regulations and forcing workers to work despite the strike?

It might be that these reports about fire regulations are untrue.

Anyway, the recklessness in firebombing a building without caring if human life was endangered was reprehensible.

But wouldn’t you think that viewers of reports from Greece, appalled by the deaths of the bank workers in that inferno, would have been given this information about the claims on fire regulations, with the appropriate caveats?

The Financial Times reported last Thursday that Greece spent a larger proportion of its GDP on defence than virtually any other member of Nato (2.5%). Greece’s current shopping list, the Financial Times reported, included a €1bn order for two new German-designed submarines and two French made frigates costing another €1bn, plus an undisclosed number of fighter aircraft. Conscription also remains in place in Greece, admittedly now cut from 12 months to nine months.

All this, incidentally, was approved earlier this year by the reigning Pasok ‘socialist’ government.

This is the same government that drove through the Greek parliament last week the €30bn austerity programme, which will devastate the livelihood of the average Greek. This was part of the package imposed by the EU and the IMF, which apparently didn’t object to all the spending on submarines, frigates, fighter aircraft and conscription.

The OECD report, ‘Growing unequal: income distribution and poverty in OECD countries’, shows that Greece is one of the most unequal countries in all of the OECD, almost as bad as Ireland.

Is it any wonder that people on the streets of Athens last week were saying ‘‘We are not Ireland’’, when inequality in Ireland is even worse than in Greece? As in that country, the burden of the fiscal adjustment here has to be borne in large measure by those on low incomes and on welfare, but in Ireland, the austerity regime is accepted generally - except by old age pensioners.

The EU Commission report, European Economic Forecast: Spring 2010, published last week, revealed that Greece had a healthy record of economic growth from 2006 to 2008 (4.5%, 4.5% and 2.0% respectively).

Its economy contracted by just 2% in 2009 and would contract by just 1% in 2010, returning thereafter to growth. (The same report showed that Ireland contracted by 7.1% in 2009 and will contract by 0.9% in 2010.) But, because of the austerity programme, Greek growth will be far lower in 2010 and 2011.

What is the sense of this?

Why impose a programme on a country that makes it more difficult for it to repay its debts?

One of the criticisms levelled at Greece, according to last Thursday’s Financial Times, is that there are not enough golf courses in the country, nor enough marinas nor ‘‘pricey adventure holidays’’.

(This is on page 11 of that newspaper, in a full-page piece headlined ‘A Herculean task’).

Golf courses on the site of the origins of our European civilisation (such as it is). Golf courses on the sites of the great battles that repelled the Persians in the 5th century BC, events which have framed Europe ever since. (How different would it have been had the Persians prevailed?)

This was where the first experiments in democracy occurred, where great literature and philosophy emerged which enriched European lives for millennia, and from where the culture that infused Christianity came.

In that infamous tirade against Islam, Pope Benedict XVI said Christianity was a fusion of the teachings of Christ with Greek culture and, as a consequence, Christianity was not just a religion of ‘the Book’ (as was Islam), but one of reason as well. And the gurus of economic recovery want golf courses there.

Isn’t there something loopy about the tyranny of these financial markets? A few thousand bond brokers in the financial world around the globe can so manipulate the world’s finances that they cause misery to hundreds of millions and, in the process, make fortunes piled on fortunes for themselves. Is this the best the world can do in managing its affairs?

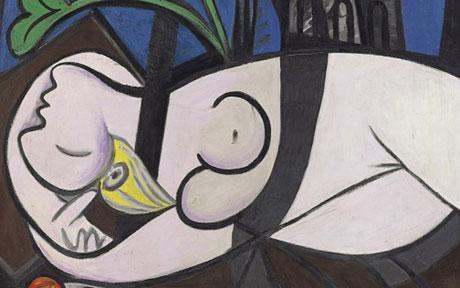

On the page opposite that article on Greece in last Thursday’s Financial Times, there is a reproduction of Picasso’s painting Nude, Green Leaves and Bust. This accompanied a report that the painting had been sold at a Christie’s auction last Tuesday in New York for $106m (€83m). It was a record price for any artwork sold at auction, ever, anywhere.

‘‘This was a stellar night for Christie’s and for the art market,” said a spokesman. In all, at that auction last Tuesday, art works valued at $335.5m changed hands.

And wouldn’t Nude, Green Leaves and Bust be an appropriate emblem for Ireland nowadays?