It's called hunger

That we can’t, that we don’t, ensure that nobody in our society goes without food says something about the kind of society that is being created for us. By Michael Taft.

A new report is out - Constructing a Food Poverty Indicator for Ireland. It estimates that one in ten people experienced ‘food poverty’ in 2010. In other words, hunger. I know the phrase ‘must-read’ is sometimes over-used, but this is truly a must-read report. The very idea that one-in-ten of our neighbours suffer from food poverty is truly frightening. Maybe you won’t be guaranteed a job, maybe you won’t be guaranteed free medical care regardless of your need, but surely in a civilised society we can ensure that no one goes without food. That we can’t, that we don’t, says something about the kind of society that is being created for us.

This estimate produced by Caroline Carney (General Council of the Bar of England and Wales) and Bertrand Maître (ESRI) is based on a careful methodology. It uses deprivation indicators that relate to food in the EU’s Survey of Income and Living Conditions:

- Inability to afford a meal with meat or vegetarian equivalent every second day

- Inability to afford a roast or vegetarian equivalent once a week

- Whether during the last fortnight, there was at least one day (i.e. from getting up to going to bed) when the respondent did not have a substantial meal due to lack of money

- Inability to have family or friends for a meal or drink once a month

While they produce a number of findings based on these indicators, in the final analysis they omit the last one – having family or friends over once a month for a meal or drink, though they acknowledge the importance of this indicator:

“This paper does not suggest that this item is not a valid indicator of deprivation per se but is concerned with its ability to identify food deprivation specifically. This item captures deprivation of social participation, in particular social participation relating to food and drink. However the other deprivation items being used by this research capture deprivation that is specific to not affording adequate food.”

I don’t intend to reproduce the numerous tables contained in the report to show the extent and scale of food poverty. However, I would like to draw attention to the following findings:

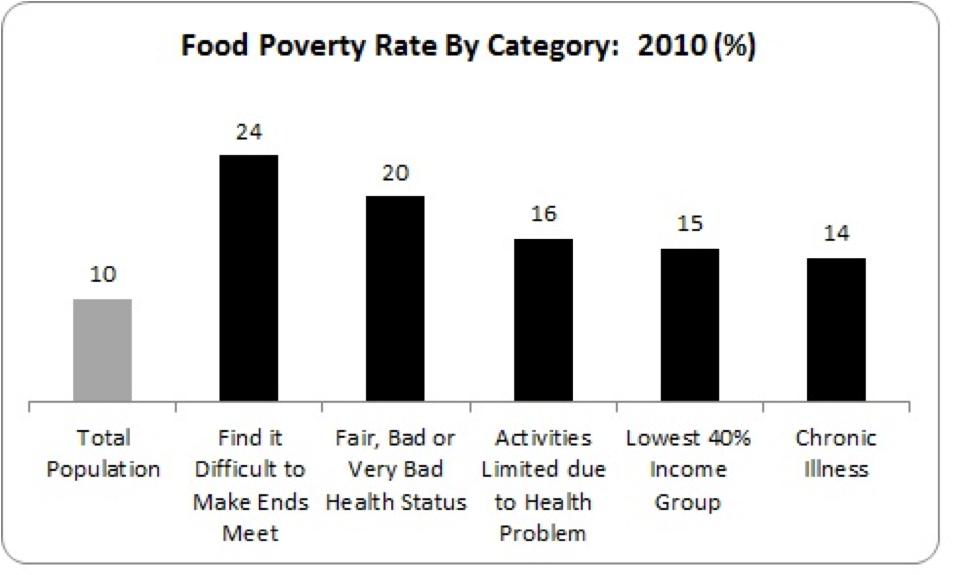

For those who find it difficult to make ends meet, the food poverty rate is 24% – which means that one-in-four in this category experience one of the three indicators used above. Those suffering from poor self-reported health status rank close behind.

For those who find it difficult to make ends meet, the food poverty rate is 24% – which means that one-in-four in this category experience one of the three indicators used above. Those suffering from poor self-reported health status rank close behind.

There are a couple of things to note. First, these numbers are probably an underestimate. The authors point out that the data they were using, from the EU-SILC report, covers only private households. This would exclude homeless, asylum seekers, travellers and people in institutions. As the report rightly points out, “These groups may be more vulnerable to food poverty.”

Second, this only goes up to 2010. We should not be surprised if the food poverty rate has risen since then. Budget 2011 contained a number of highly regressive measures (cuts in social protection payments, the flat rate tax in the form of cutting personal tax credits, the USC) along with falling employment and income for key groups. Budget 2012 contained social protection cuts in particular items and across-the-board cuts in real terms (that is, after inflation), along with the regressive Household Charge.

I urge you to have a look at this highly accessible report. Flip through the tables and graphs. At least read the conclusion. It may not be as sexy as the latest story about property prices or public sector allowances or some minister’s latest peccadillo – but can we please have some perspective in this debate.

Some of our neighbours are going hungry.

Carney Maitre - Constructing a Food Poverty Indicator for Ireland

Image top: Luke Hayfield Photography.