Raising the floor

Raising the income floor for low-income households is not just about equity, or sharing the pain, or ‘too poor to pay more’. It’s also about a growth strategy. By Michael Taft.

In a previous post we looked at how our rich are richer than the rich of other European countries. Our rich grab a higher proportion of disposable income. That’s one side of the coin. Let’s look at the other side: that our ‘poor’ take a lower proportion of disposable income than the poor of other countries. This issue, finally, is gaining some currency. Social Justice Ireland has pointed out that inequality in Ireland is rising under current Government policy, while Vincent Browne wrote on the same theme yesterday. {jathumbnailoff}

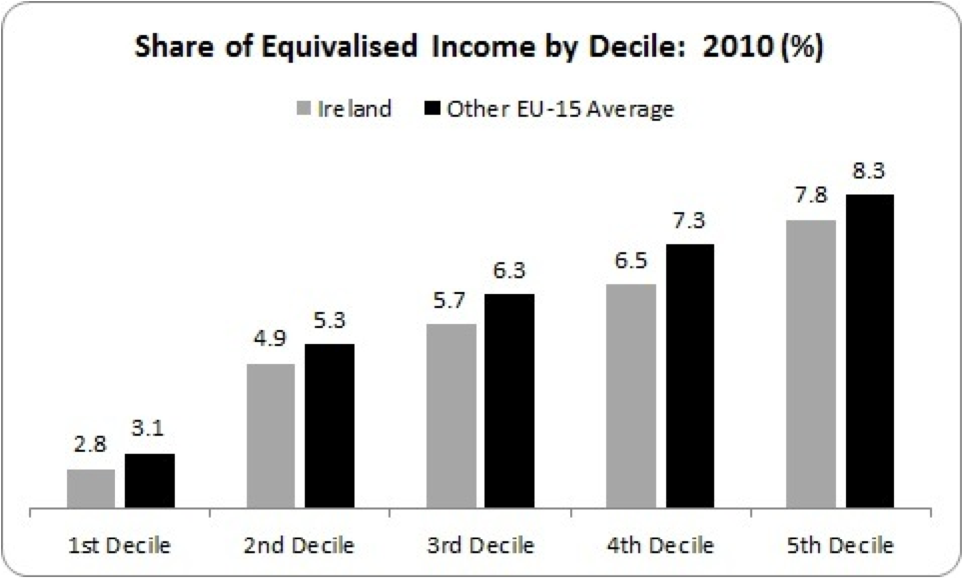

In every decile in the lower half, the take of national income is less than the EU-average (for an explanation of equivalised income, see the post on high incomes). The difference in the numbers may seem merely fractional, but they add up at the national economic level (and don't forget - the top decile, the top 10%, take over 26% of all national income).

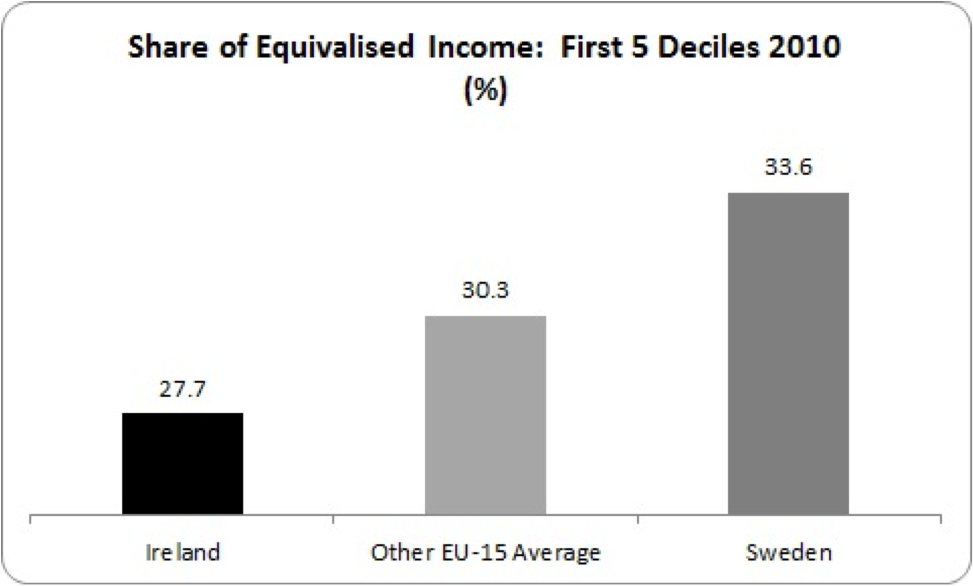

Let’s take the combined share of the first five deciles. We should bear in mind that the average household income of the 5th decile is still very low: only €607 per week for nearly three people in the household. That compares to a national average of €830 per week.

The gap is significant. If Irish incomes in the bottom half were to rise to the average of other EU-15 countries, they would receive a 10% boost. If they rose to Swedish levels, they would receive a 20% increase.

However, the comparative situation could be worse today. These figures are from 2010. Since then, we have had two highly regressive budgets. In the 2011 budget, Fianna Fáil cut social welfare rates and Child Benefit, cut personal tax credits (in effect, a flat-rate tax increase) and introduced the Universal Social Charge. This was highly damaging to low-income households. The Fine Gael-led government’s first budget also cut social protection (though not rates), increased highly regressive VAT rates and introduced the flat-rate Household Charge. Therefore, we should expect deterioration in the living standards of low-income groups.

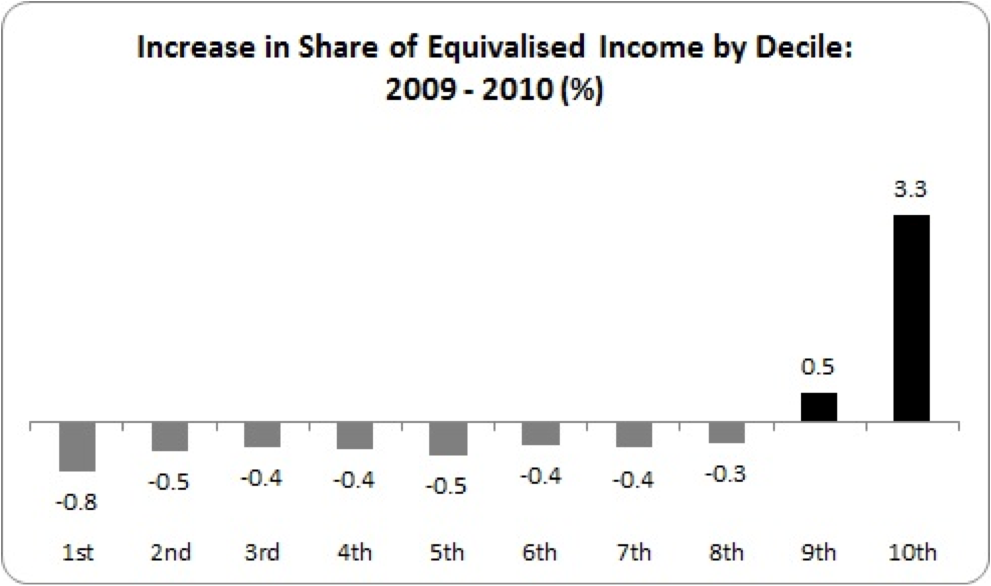

By how much? This looks at the increases in the share of equivalised income between 2009 and 2010.

All deciles found their share of national income falling – with the exception of the top two deciles. The lowest decile had 3.6% of total income in 2009. This fell to 2.8% the following year. The highest income groups’ share increased – from 23.3% in 2009 to 26.6% the next year. That this trend is likely to continue can be seen in the ESRI’s analysis of Budget 2012, which it described as the most regressive budget since the recession hit Ireland.

If Ireland’s poorest 50% of households found their incomes increasing to average EU-15 levels, what would this mean in euros and cents?

- Increase to the average of other EU-15 countries: €2.4 billion

- Increase to Swedish levels: €5.5 billion

In aggregate, those in the bottom half of the income scale would receive between €2.4 and €5.5 billion if our income distribution were structured along EU norms. What would this mean for each adult? Here we are going to mix-and-match – using the adult breakdown in each household from the EU Survey of Living and Income Conditions and the recent Census figures. So this should be treated with caution. Hopefully, though, it will give us broad figures that we can target.

According to the 2011 census there are 4.6 million people in the state. According to the EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions, 40% of all residents live in the 1st to 5th deciles. On this basis, if the income share of the lower half were increased to EU levels, each individual would be receiving the following:

- Increased to the average of other EU-15 countries: €1,317 per year

- Increased to Swedish average: €2,988 per year

This simple tabulation doesn’t distinguish between adults and children or between those at work, home-carers, retired people or those on social protection. However, if our income distribution system mirrored that of EU norms, lower income individuals would be getting over €1,000; and even higher if compared to more egalitarian economies.

What are the implications?

Clearly, the next budget must be redistributive – substantially so. This requires increased taxes on higher incomes, investment to get people back to work, and budgetary increases for those on low incomes (e.g. Family Income Supplement for low-paid working families and basic social protection payments).

But greater equality is not just about a progressive budget. Those in low-paid work need support – whether that is increased minimum wages, the right of part-time workers to get full-time work in their firm (as MANDATE highlights) and protection of working conditions. However, all this is just as problematic as a Fine Gael finance minister bringing in a progressive budget. The Minister for Enterprise (also Fine Gael) is seeking to drive down the wages and working conditions of those in the low-paid sectors. Recently, the Dáil voted to effectively scrap the Sunday premium for low-paid workers under the JLC system, leaving them at the whim of employers. This, along with other changes in the JLC system, will drive down the incomes of those in the lower half of the national income table.

Raising the income floor for low-income households is not just about equity, or sharing the pain, or ‘too poor to pay more’ (it is these things in bucket loads). It’s also about a growth strategy. Low-income groups spend a very high proportion of their income. Getting a boost in income is merely a conduit for more spending in the economy, which raises GDP, benefits enterprises reliant upon domestic demand, and increases or protects employment. Raising the income floor makes good economic sense.

So Budget 2013 will be a budget of choices. The Government can choose to be progressive – and Labour, in particular, can insist on it. If they don’t, we can expect to see inequality widen and impoverishment grow. {jathumbnailoff}