The hollowness at the heart of human rights 'concern'

This business of human rights seems, in part, to be a device for privileged people to escape the discomfort of being the beneficiaries of a hugely unequal society. By Vincent Browne.

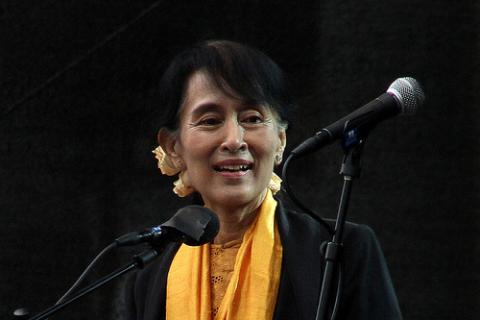

It was heartening to witness some 2,000 people packed into the Grand Canal Theatre on 18 June to honour one of the world's iconic campaigners for human rights, Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma.

It was heartening to appreciate that, so ardent was the commitment of those two thousand people to the cause represented by Aung San Suu Kyi, many of them paid up to €150 a ticket for the thrill of attendance.

Heartening also that some of our homegrown icons, Bono and Bob Geldof among them, were among the welcoming party. (Bono seems to be a serial welcomer for, it appears, he welcomed Aung San Suu Kyi to Norway, welcomed her to Ireland and someone said he was planning on welcoming her back to Burma when she returned.)

He and Sir Bob are very much among the 'in crowd', obviously, for they referred to the guest as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi ('Daw' means 'aunt' in Burmese).

Aung San Suu Kyi comes from a distinguished background. Her mother was a formidable woman, serving for a while as the Burmese ambassador to India. Her father, Aung San, is regarded as one of the founders of independent Burma, whose status was much enhanced when Winston Churchill described him as a "traitor rebel leader".

Curiously, Churchill might have had a point, for Aung San, having been a founder member of the Burmese Communist Party, collaborated with the Japanese during the Second World War, breaking with them only towards the end, before becoming the leader of pre-independence Burma. He was assassinated just before independence, when his only daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, was just two.

She had a privileged upbringing and education - private schools (Methodist and Catholic, although she has always been a Buddhist), Oxford and the University of London. Compared to the vast majority of Burmese people, she has always been well off financially.

All of this, in many ways, makes her commitment to democracy and human rights in Burma all the more impressive.

She married an academic, Michael Aris, in 1972. They lived in Oxford for several years and she gave birth to their two children there. When she returned to Burma in 1988 to look after her ailing mother, she got involved in Burmese politics.

Aris lived there with her for a few years before returning to England in 1995. They never met again, as he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997. The Burmese government refused to grant him a visa and she knew that if she left Burma, she would not be allowed to return. He died in 1999. She was also separated from her children from 1995, meeting them again only last year.

In 1990, her party, the National League for Democracy, won 59 per cent of the votes in a parliamentary election and she was the likely new prime minister. Instead, she was placed under house arrest, where she remained for 15 of the following 21 years, punctuated by periods of imprisonment.

There has been some relaxation of repression in Burma over the last few years.

This led first to her release from house arrest, then her election to the Burmese parliament and, now, freedom to travel abroad without fear of being denied return.

Throughout all these torments and turmoil, she has remained dignified, thoughtful and eloquent and, on 18 June, she received yet another honour, Amnesty International's Ambassador of Conscience award.

But at the celebration for Aung San Suu Kyi, I thought there was something fake about it all, not about her at all, but about the event. There is a hollowness about this 'human rights' thing - not that human rights are not crucial to people throughout the world.

But the support for human rights in Nepal, Tibet, China or anywhere far away - without much regard for creating the economic and social circumstances in which human rights might mean something to people here and elsewhere - seems to me to be fake.

America engages in periodic celebration of the 'freedom' its people enjoy. George W Bush thought terrorists attacked America because they hated its 'freedom'.

According to the US Census Bureau, 46.2 million people in the United States of America live in poverty - 15.1 per cent of the population. For blacks, the poverty rate is 27.4 per cent, and for Hispanics it's 26.6 per cent.

The poverty threshold is around €9,000 for a single person and around €18,000 for a family of four.

What does freedom mean to these 46.2 million people? What are the values of personal liberties to them? What do human rights mean for these Americans?

Similarly here in Ireland. What do human rights mean here for the third of the population living on the margins or below the margins?

What good are personal freedoms unless one has the means to exercise them? What do human rights mean to them when the ethos, practices and reflexes of society belittle them?

This human rights business seems, in part, to me to be a device for privileged people to escape the discomfort of being the beneficiaries of a hugely unequal society. {jathumbnailoff}

Image top: kjelljoran.