Wishful thinking on mortgage arrears will get us nowhere

Establishing a cabinet sub-committee to study the problem of mortgage arrears, which Enda Kenny has indicated he’s doing, and wishing for the banks to “show a greater urgency” is simply not good enough. By John Farrell Clark.

If there was ever a time to make an argument for politicians and the Central Bank to take unprecedented and bold action in the banking sector, now is the time. There is an ever increasing mortgage arrears problem that has been described as “the biggest issue facing the Irish people”, a topic I’ve written about before. If it is not clearly and aggressively solved, the people will once again be tapped to pay for it, to say nothing of the distress it will continue to cause homeowners.

Banking is a regulated business and it was the responsibility of politicians and the Central Bank to do their job. Unfortunately, for us, they didn’t. They can blame each other for the creation of a property bubble, but collectively they caused the problem by allowing the banks to act irresponsibly in their lending practices. They forgot to say “No”, or to at least put on the brakes to curtail lending to an obvious run-away property market. Now it’s their job to fix it.

But so far the politicians and the Central Bank are leaving it up to the banks to solve the problem. However, we cannot expect the same institutions that caused the problem in the first place to find a fix that makes sense, not only for their shareholders but also legitimately distressed homeowners. They have had years to properly address the problem, but to date their response can only be described as timid, if not pitiful. As a retired commercial banker myself - and I’ll not be making many friends in the banking industry by saying this - sometimes you’ve got to call it the way it is.

Banking polices, including lending criteria, are formulated at the executive level and approved by the board of directors. They made the decision to flood the property market with questionable loans (many of which are now underwater and/or non-performing) as a means to increase earnings and shareholder value along with paying out bonuses to executives.

In the 1980s in Orange County, California I worked for a bank that was under the same kind of pressure, but, knowing that the market was overheated and oversaturated, we made the decision to curtail our property lending; and the regulators agreed with our decision. It was prudent to not have a loan portfolio overly concentrated in property. We chose to forego short-term earnings for the sake of long-term financial stability.

Irish lending institutions now have the same responsibility to establish new and far-reaching polices on a wide scale basis to address solutions to problems they helped create. However, one can only assume they are in a state of denial. Their bunker mentality is allowing for dealing with this problem only on “a case by case basis”.

Part of their argument is that some borrowers are making the strategic decision not to make their loan payments as a means to obtain better terms, even when they have the wherewithal to do so. Although this may in fact be true, it looks like a red herring in that banks, with support from government officials, are using it as a means to divert attention from the real problem at hand. It is simply wrong to base their position on the unethical behaviour of some people in order to ignore the legitimate needs of thousands of others.

In a way this convoluted tactic makes some sense, at least from their point of view. The idea of debt forgiveness, even if only partially, and/or debt restructuring through rewriting terms as long as forty years or exchanging a portion of the debt for partial ownership, is abhorrent to banks. But the point is they made the loans that have caused problems and now they need to be part of the solution on a broad basis. Doing it piecemeal just will not cut it.

Meanwhile their balance sheets continue to deteriorate, and they will eventually reach a point where additional capital will be required to maintain financial viability; who in their right mind will want to invest in such a business? Returning to the market to generate capital is illusary; all of which means that in the end it will be the people, who had no role in creating the problem, that will be tapped.

It was reported in the Irish Independent that Enda Kenny “has called on Ireland’s banks to show greater urgency in dealing with the mortgage crisis” and that “the arrears problem was now the single biggest issue facing the Irish people.”

He was quoted as saying: “I would like to think the banks themselves would show a sense of greater urgency in sitting down with the borrowers - in each case different - and work out what is the best solution, so people can hold onto their houses and at the same time not end up in a situation where they won’t be able to meet what is a difficult challenge now.”

And therein lies the problem. This passing the buck, finger-pointing and sitting on their hands really needs to stop. Establishing a Cabinet sub-committee to study the problem, which the Taoiseach indicated he’s doing, and wishing for the banks to “show a greater urgency” is simply not leadership.

The politicians and the Central Bank failed in their respective jobs to properly regulate the banks in the first place. Now it’s their responsibility to put in place laws that not only protect homeowners but also the banks themselves. It’s an intervention that is needed.

Legislation needs to be drafted and passed to take control away from the banks as to the mortgage arrears problem and, if need be, to temporarily suspend statutory capital to asset ratios. There are solutions such as a debt forgiveness of that portion of the mortgage over a certain percentage of present market value. Iceland has taken such action and the IMF supported this decision.

It is understandable and reasonable that only loans created during a prescribed time period would qualify. It has been suggested from 2004 to 2008 or 2009. It would follow along the same lines of the new policy of increasing the amount of mortgage interest relief.

The new mortgages, or more aptly called “legacy loans”, could then be rewritten for as long as 40 years, thereby making them serviceable. Or a portion of the new debt could be exchanged for partial ownership. At least this way, primary ownership of family homes would stay in the family as a legacy for future generations rather than their being lost to foreclosure - thereby causing the banks to “write off” the loan from an accounting standpoint, which in turn would require raising more capital.

The banks have had time to act responsibly and they have squandered it. When an industry is under the provisions of State regulation, sometimes there is a price to pay. It is the people’s interest that is at stake. Now is the time for the Government to act, not ponder. Wishful thinking will get us nowhere.

And Enda and Michael? This is not a tough call. The Government owns almost outright two of the banks, has a third under its control and has a significant ownership in another. You own it. Do the right thing and fix it. You have the power and the people are depending on you. And if you don’t? Well, that’s what elections are about. {jathumbnailoff}

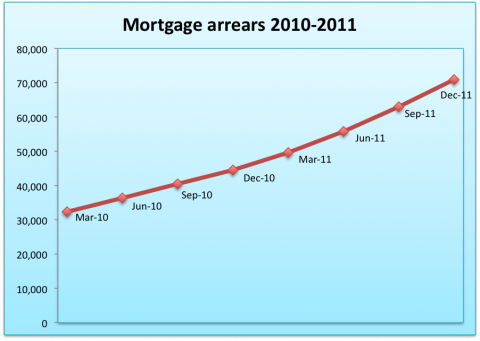

Image top: Total number of mortgages in arrears of 90 or more days in 2010 and 2011. Source: Central Bank of Ireland.