Abortion, resistance, and the politics of death and grief

We may be seeing the opening of a gap between deserving and undeserving women in the campaign for abortion legislation. How might this gap be closed? By Mairéad Enright.

In recent months, spurred on by the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in A, B & C, by the 2011 observations of the UN Committee Against Torture, and by Ireland’s Universal Periodic Review, we have seen a significant push towards legislation ‘for X‘. To this end, in February, Clare Daly TD introduced a Private Member’s Bill in parliament, which was debated and rejected in the Dáil yesterday. For its part, the Government has appointed an expert group, chaired by Seán Ryan, which will report on the possible legislative implementation of A, B & C in the summer (see the IFPA’s detailed critique of this strategy here). The majority of TDs speaking yesterday seemed open to the proposal to legislate for X in principle, albeit they did not support this specific Bill. It may be that we are on the cusp, finally, of some legislative movement on abortion in Ireland.

Rather than dwelling in detail on the contents of any future legislation, I want to think about the figurations around whom those who advocate abortion legislation have based their politics. The image of the woman who terminates her pregnancy as a ‘murderer’, ‘sinner’ and ’fornicator’ made an unwelcome appearance in yesterday’s parliamentary debate, courtesy of Fine Gael’s Michelle Mulherin TD. But this debate about abortion is different from those that have gone before in many ways. One is that on this occasion, more than ever before, Irish women who have been affected by abortion and their families have identified themselves, and have placed themselves in the space formerly occupied by the abstractions onto whom immorality is so easily projected, and on whom so much of anti-abortion discourse depends.

There are two such groups of women. The first, smaller group, is the group of the dead – women such as Michelle Harte, and, Sheila Hodgers, whose pregnancies were incompatible with cancer treatment. The X case contemplates that women have a constitutional right abortion in Ireland if they will die without it (or rather if they refuse to die in order to ‘give life’ ). We know because of Michelle Harte’s intervention that this right is not vindicated. We know because of Brendan Hodgers how such women have died. The second group consists of women whose deeply desired babies were diagnosed in utero with medical conditions – such as Edwards Syndrome or anencephaly - which are incompatible with life. Four such women - Jennie McDonald, Ruth Bowie, Amanda Mellett and Arlette Lyons – met with TDs before yesterday’s debate, and published their stories and photographs in the Irish Times. They spoke about the abortions they had obtained in England because they are unavailable on the island of Ireland. They followed Amy Dunne – known as “Miss D” in the judgment in which the High Court considered her entitlement to travel for an abortion - who was identified and interviewed on Prime Time in 2010.

These women and their families have constituted themselves as citizens, entitled to speak on their own terms and in their own names about the State’s shaming, shameful, and often violent responses to them. Speaking in their own names, in their particularity, they are less easily brushed aside than were X, C, D, A, B and C. The importance of the interventions made by and on behalf of these named women cannot be understated. They are the abortion debate’s Antigones[1]. They have consecrated to Irish law, not a politics of victimhood, but a difficult and resistant politics of pain, death and grief. They have done it not - as their anonymised counterparts did - by going to law (though litigation has mattered very much here too) but by insisting on entitlements which reach even beyond the decided cases, and by speaking a language of state responsibility and citizenship which should have important resonances for future debates on abortion.

However, this new politics says nothing for the majority of Irish women in need of abortions; those whose decisions are perhaps more vulnerable to the criticisms of moral conservatives, and are less likely to move TDs to tears. Even legislating for X and for medically necessary terminations, most women and their partners would still be obliged to travel, to pay, to export unwanted pregnancies, to relieve the government privately and individually of its responsibilities. They would do so burdened by stigma, mystification, secrecy, grief, sometimes by poverty or isolation (see further, the IFPA’s Irish Journey). If they did not or could not travel, they might place their health at risk by consuming abortion pills purchased online. Some would not be permitted to travel, because, like Amy Dunne, they are children in the care of the State.

When I read the article in the Irish Times about the courageous women who are campaigning for legalisation of ’termination for medical reasons’ I was struck by the line “[t]hey know, for example, that being categorised with ‘pro-choice’ groups could lose them support”, and the reporter’s explanation that their campaign sought to distinguish itself from the broader ‘pro-choice’ movement through its emphasis on the fact that these women had abortions because they were carrying foetuses with horrendous chromosomal defects. I wonder whether we are seeing – despite the best efforts of campaigners such as Claire Daly TD – the opening of a gap between deserving and undeserving women in the campaign for abortion legislation. How might this gap be closed? We are in trouble if the unsettling of Irish abortion law’s abstractions stops here.

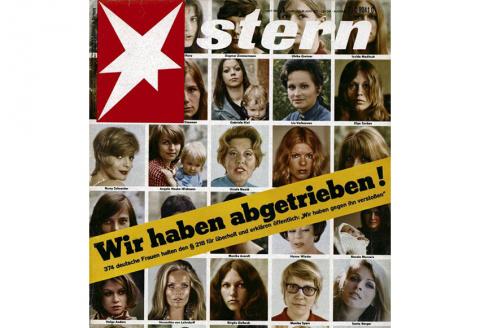

What would it mean for a third group of women – who have had abortions for social, economic or ethical reasons – to reveal their identities? One model for intervention comes from the feminist movement of the 1970s. In 1972, a year before Roe v. Wade, some 50 American women consented to have their names published in the inaugural issue of Ms. magazine under the declaration ‘We Have Had Abortions’. In 2006, they re-staged the initiative, this time collecting 5000 names. This American campaign followed the 1971 examples of the French ‘Manifesto of the 343 Sluts’ (Simone de Beauvoir and Catherine Deneuve were two) and the West German magazine Stern (pictured above) – publications in which well-known women effectively dared their governments to enforce the laws criminalising abortion. Part of the point was that many of the women who signed these documents had not had abortions, but signed them just the same. In West Germany, the Justice Minister received 90,000 further ‘confessions to abortion’ from women inspired by the Stern campaign. The power of those campaigns is comparable to that of the Antigone-like interventions discussed above because they also turned on naming and identification; on refusal of anonymity. They were also powerful enactments of solidarity, because they moved one crucial step beyond the familiar Irish language of sympathy (“our daughters, our sisters, our neighbours”), of empathy (‘there but for the grace of God’) to the far more dangerous commitment of identification (“we did’, ‘I did”). As Bonnie Honig reminds us, there is a role for Ismene as well as Antigone; for the more passive cautious sister as well as for the agonist in centre stage. The struggle for abortion law will depend on how the broader community of Irishwomen thinks about solidarity.

[1] Three Irish Antigones were published in 1984, including this one by Brendan Kennelly; a “feminist declaration of independence”. That was the year of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, of Anne Lovett in Granard and Joanne Hayes in Abbeydorney. Kennelly wrote an Antigone to face this remorseless legal assault on women; an Antigone who is beaten, silenced and buried in ‘a black hole among the rocks’, but who “bows for nobody and nothing”. {jathumbnailoff}

Originally published on Human Rights in Ireland under a Creative Commons by-nc-nd 3.0 license.