Apphole

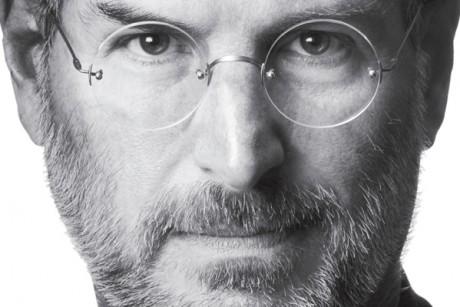

When Steve Jobs died last year, on October 5th, at the age of 56, from pancreatic cancer, it was the most important death in the world. Not in terms of political significance – the deaths of Osama bin Laden, Muammar Ghadafi, and Kim Jong-il were much more momentous in that respect. Not in terms of fame either – Liz Taylor and Joe Frazier were greater celebrities than Jobs when they died. And not in terms of contribution to the arts – the painter Lucian Freud, the film director Sidney Lumet (Dog Day Afternoon, Network), and the playwright Arthur Laurents (West Side Story) added more to the stock of human culture than he did. By James Mahon, Yale University.

Jobs' death may not even have been the most tragic death of last year (Amy Winehouse?). No. His death was the most important because at the time of his passing he was changing, at an almost yearly rate, the daily lives of millions of people.

After his fateful visit to Xerox's headquarters in December 1979, when they revealed their Graphical User Interface (GUI) to him (basically, how to make computers do things by moving around a mouse and clicking on images), Jobs said "I saw what the future of computing was destined to be." This statement is incomplete in two respects. First, that future was not "destined to be" without the genius of Steve Jobs. The people at Xerox did not even appreciate what could be done with their own interface. Second, it was not just the future of computing that he grasped. By the time of his death Jobs had revolutionized not merely the personal computer industry – to paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, all modern personal computers come from one computer by Steve Jobs called the Macintosh – but also the music industry (iTunes and the iPod), the phone industry (the iPhone), the computer software industry (the App Store), the digital books and magazines industry (the iPad), the digital content storage industry (iCloud), the animated film industry (Pixar), and the retail industry (the Apple Retail Store).

Given that the WorldWideWeb was created on a computer (the NeXT Computer) that Jobs designed after he was booted out of Apple in the mid-1980s, he may even take some credit for the existence of the web. The Super Bowl commercial that launched the Macintosh in 1984, brilliantly depicting IBM as Big Brother (his idea, Ridley Scott's direction), and watched live by 96 million people, was later voted the greatest commercial of all time. Many people consider his autobiographical commencement address at Stanford University in 2005 to be the best ever given (watch the video below). As CEO of Apple he managed to turn product demonstrations into an art form (by working on them obsessively to get everything right). What cannot be disputed, however, is that by the time of his death in late 2011 the company that he founded, Apple, Inc., originally the oxymoronically fun-titled Apple Computers, Inc., was the most valuable company in the world, and Steve Jobs was the world's greatest CEO.

Jobs was, in a very real sense, a visionary. But – as this biography is at pains to point out – Jobs was not simply a man with lots of ideas, trying to get them developed. He was not a Nikola Tesla. He was determined to make products that would work and that would be used by everyone.

As he used to say, "Real artists ship." When iTunes was launched in 2003, it sold six million songs in 6 days. At the end of 2010, Apple had sold 90 million iPhones. When the Apple Store opened in Manhattan in 2007, it attracted 50,000 visitors per week. It grosses more than any other store in New York. (Just try on any given day to squeeze your way into the Jobs-commissioned I. M. Pei-designed floating staircase, so that you can walk on the bluish grey sandstone excavated from the family-owned quarry of Il Casone, in Firenzuola, outside Florenece).

Jobs also said, quoting Picasso, "Real artists steal." (The 'stealing' from Xerox is often said to be a case in point). One thing that both of these pronouncements reveal is just how much Jobs saw himself as an artist. What obsessed him was beautiful design. As he once said about Apple products, "we're really shooting for Museum of Modern Art quality." A telling observation made by Isaacson in his biography is that Jobs "had a great love for some material objects, especially those that were finely designed and crafted, such as Porsche and Mercedes cars, Henckels knives and Braun appliances, BMW motorcycles and Ansel Adams prints, Bösendorfer pianos and Bang & Olufsen audio equipment." As this list indicates, Jobs' preferred aesthetic was modern, even Bauhaus. He was a great admirer of the Functionalist industrial designer for Braun, Dieter Rams, who insisted, "Less is better." The designer he hired for Apple was Hartmut Esslinger, of frog design. The original Apple brochure stated, "Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication."

Jobs was less of a genuine artist himself, however, and more of an arbiter of taste. As his ex-girlfriend, Tina Redse, put it, "Steve believed it was our job to teach people aesthetics, to teach people what they should like." One of his personal heroes was Joseph Eichler, the American post-war real estate developer responsible giving for giving the booming new population of Northern and Southern California the pared down, glass-filled, clean-lined modernist houses now known as "Eichler Homes." Eichler improved the lives of people by giving them houses that he knew were beautiful, even if they didn't realize that this was what they needed. As Jobs said, "customers don't know what they want until we've shown them." He refused to do any consumer testing, claiming that Henry Ford never listened to what customers said they wanted, and that Alexander Graham Bell never did any market research before inventing the telephone.

Joseph Eichler, and also Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid, were people who, Jobs thought, exemplified the intersection between technology and art that he loved. Although he grew up near Stanford University, Jobs chose to enroll in Reed College, in Portland, Oregon, a hyper-intellectual small liberal arts college where students are not shown their grades and where a disproportionate number of students go on to do PhD's. Famously, it was there, now as a dropout sitting in on classes for free, that he went to lectures on calligraphy given by an ex-Trappist monk, Robert Palladino, which later inspired him to create the different typefaces available on the Macintosh. That meant that every computer ended up with them, because, as he enjoyed saying in his Stanford address, "Windows just copied the Mac." It was the perfect example of art meeting technology.

As that swipe about Windows reveals, the real competitor to Apple was not IBM, but Bill Gates's Microsoft. Isaacson brilliantly presents the rivalry between these two companies, and individuals, as a rivalry between two different business models. Microsoft believed in developing software that was compatible with computers made by other companies (think Dell or Hewlett-Packard or Compaq or Gateway) as well as its own, and licensing it to them. Whenever anyone says "PC" (short for personal computer), they mean some computer like this that runs Microsoft software. This is the 'open' business model. Apple created its own software and computers, and refused to make its software compatible with other computers. This is the 'closed' business model – ironic, since it gives users no freedom. The 'PC vs. Apple' decision is between a much wider selection of machines and software packages at, usually, a cheaper cost, and Apple's limited selection of (beautiful, but more expensive) computers (and phones, and pods, and pads) running their own exclusively latest software. Jobs's obsession with the end-to-end integration of software and hardware was always derided by Gates, but in his final meeting with Jobs in May 2011, Gates said, "I used to believe that the open, horizontal model would prevail. But you proved that the integrated, vertical model could also be great." Jobs kindly responded, "Your model worked too." Isaacson nicely adds that each had a caveat. Gates thought that the Apple 's closed model only "works well when Steve is at the helm." Jobs thought that Microsoft's open model "produced crappy products."

Along with Jobs's controlling 'closed' business model was a style of running Apple that made people say that he would have made a good King of France. Jobs was happy to admit this: "I am a tyrant. But I am usually right." His colleagues concurred with the first claim at least: "Under Steve Jobs, there's zero tolerance for not performing." He was notoriously difficult to work with. About his first job working at Atari, the legendary games maker, he said, "the only reason I shone is that everyone else was so bad." For Jobs, everyone in the business was either a genius or an idiot, and he only wanted to work with geniuses. E

Even with geniuses, he was manipulative. Isaacson is enamored of a reference made by a software engineer, Bud Tribble (seriously?), to "The Menagerie," a two-part episode of the original Star Trek series in which the crew of the Enterprise encounter a race of aliens called Talosians who have the ability to distort human beings' perception of reality and make them hallucinate. Jobs was said by Tribble to have the ability to manipulate your perception of reality – to create a "reality distortion field" – so that you did what he wanted you to do. As it were, these were self-fulfilling distortions. What this amounted to, it seems, was Jobs making a completely unreasonable demand on a person but convincing him or her that whatever it was could be done. As Jobs's sometime best friend and co-founder of Apple, Steve Wozniak, who had it practiced on him, said: "You did the impossible, because you didn't realize it was impossible." There is no doubt that Jobs considered himself superior to everyone else, and thought that the world should defer to him. Famously, he refused to put a license plate on his car, and he regularly parked in handicapped parking spots. It led to his employees coming up with the sign "Park Different." His willful refusal to accept reality may even have contributed to his death, since after an early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in October 2003 he refused to have surgery to remove the tumor for nine months, but which time it had grown and probably spread.

Jobs's tantrums and abusive treatment of colleagues and employees contributed to him being fired from his own company in 1985 in a power struggle with John Sculley, the man he hired away from Pepsi-Cola to be Apple's CEO in 1983 (Jobs was brought back into the fold in 1996 after Apple bought NeXT, and effectively took control in July 1997).

However, Jobs's boardroom antics and even his treatment of co-workers seems less damning in the end than his treatment of his family. Jobs was adopted, and knew that he was adopted. He genuinely loved his adoptive parents: "They were totally my parents." But he refused to speak to his biological father later in life, after he found out who he was, because his biological father had left his biological mother and half-sister (they were divorced). With a truly mind-boggling lack of self-awareness, Jobs refused to acknowledge the paternity of his own daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, whom he had with his then girlfriend, Chrisann Brennan, for two years.

Even after he started making court-ordered payments to Brennan, subsequent to a paternity test, he didn't have any relationship with Lisa until later, and it waxed and waned considerably. At one point, after Jobs refused to give Brennan more money for medicine, Lisa refused to speak to him "for a few years." He didn't attend her college graduation from Harvard. With respect to his three children from his marriage to Laurene Powell, it seems that he was often distant with them, especially his two daughters. About him Powell has said, "Like many great men whose gifts are extraordinary, he's not extraordinary in every realm. He doesn't have social graces, such as putting himself in other people's shoes." Presumably this includes the time when, after she was already pregnant, he dragged his heels about proposing to her, asking friends who was prettier – Powell or Tind Redse, his other ex-.

Isaacson's biography, which was commissioned by Jobs in 2003, and which is Amazon's best-selling book of the year, is extremely thorough and well researched, and is a worthy read. If it has to be faulted, it would be on the following counts. First, the writing is without any style. There is no memorable sentence in its 573 pages of narrative, other than quotations. Second, no matter how much he writes about Jobs's admiration for Bob Dylan or the Beatles or Bono (U2 was the first band to be featured in a commercial for the iPod), one never gets the sense that Isaacson shares Jobs's taste or enthusiasms. The biography reads like someone looking in on another's life. Third, although he documents Jobs's failings in his relations with others, he seems tone deaf to what many consider Jobs's greatest failing: the low-wages and dangerous working conditions of some of the 700,000 people Apple employs in China. Isaacson only mentions this figure once, in the context of a meeting between Jobs and President Obama, in which Jobs complains about the lack of people with engineering degrees in the U.S. This was a couple of months after Jobs described to the President "how easy it was to build a factory in China, and said that it was almost impossible to do so these days in America, largely because of regulations and unnecessary costs."

On a tour of an Apple factory in Fremont, California, in 1984, Danielle Mitterrand, wife of France's President Francois Mitterrand, kept asking him about workers' overtime pay and vacation time, and whether the work was hard. Furious, Jobs told the translator to tell her "If she's so interested in their welfare, tell her she can come work here any time." Last, and no doubt least, there is a surprising lack of acknowledgement by Isaacson of any other biographies of Jobs, apart from the many magazine profiles and newspaper stories referenced. There is no mention of Steven Levy's biography, Insanely Great (2000), for example, not to mention other, more recent books. There is even no mention of the made-for-TV biopic of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, Pirates of Silicon Valley (1999), in which Noah Wylie makes a convincing Steve Jobs.

On a different note, the experience of reading this biography proves to be extremely enjoyable one, for a very computer age reason. When Isaacson references an appearance by Jobs at Macworld, or even a TV commercial for a Macintosh, it is usually possible to turn to the web and actually watch the footage of the appearance or the TV commercial. Most of it has been uploaded to YouTube. There you will find the comments of others who have been led to the video by the same biography. Reading Isaacson's Steve Jobs with the help of a computer (iPhone or MacBook Air, or course) turns out to be an interactive communal experience. I have seen what the future of contemporary biography reading is destined to be.