Last night the Government signed up to €6bn more in austerity measures

The Government, in signing the Fiscal Treaty, has effectively committed itself to introducing up to €6bn more in tax increases and spending cuts in the medium-term, over and above what it has already planned. While the news in the short-term will, understandably, focus on whether a referendum will be necessary, once attention starts honing in on the details of the treaty, we will all come to understand why this agreement has come to be known as the “austerity treaty”.

The reason why we will have to endure another round of cuts can be found in the section of the text entitled ‘Fiscal Compact’ (this from a draft a few days old, at the time of this writing the final text has not been published; but there’s no indication this important section has been altered in substance):

The Contracting Parties shall apply the following rules, in addition and without prejudice to the obligations derived from European Union law.

The budgetary position of the general government shall be balanced or in surplus.

The rule shall be deemed to be respected if the annual structural balance of the general government is at its country-specific medium-term objective as defined in the revised Stability and Growth Pact with a lower limit of a structural deficit of 0.5% of the gross domestic product at market prices.

This new “structural deficit” target has received little attention so far – but it should, and hopefully it will.

We are all familiar with the Maastricht deficit of 3% of GDP. This refers to the Government’s general deficit – the level of spending over revenue. This is pretty straightforward.

The structural deficit target in the Treaty is an additional target that must be met. I will have more to say in future posts about this concept (much more – and it is just that, a concept). Suffice it to say that it purports to tell us how much deficit will remain even when the economy is running at full potential. However, it is an artificial measurement – inextricably intertwined with another artificial measurement: attempting to identify what exactly our GDP would be if it were running at full capacity. It cannot be observed in real life, like the ordinary deficit. There is no agreed methodology for measuring the structural deficit; it is subject to wide variations and to substantial retrospective revisions.

In short, if you ask 10 economists to come up with the structural deficit, you will get 20 different methodologies and 40 different results. It is nothing short of inane to put such a woolly, amorphous and erratic measurement into law, never mind the constitution.

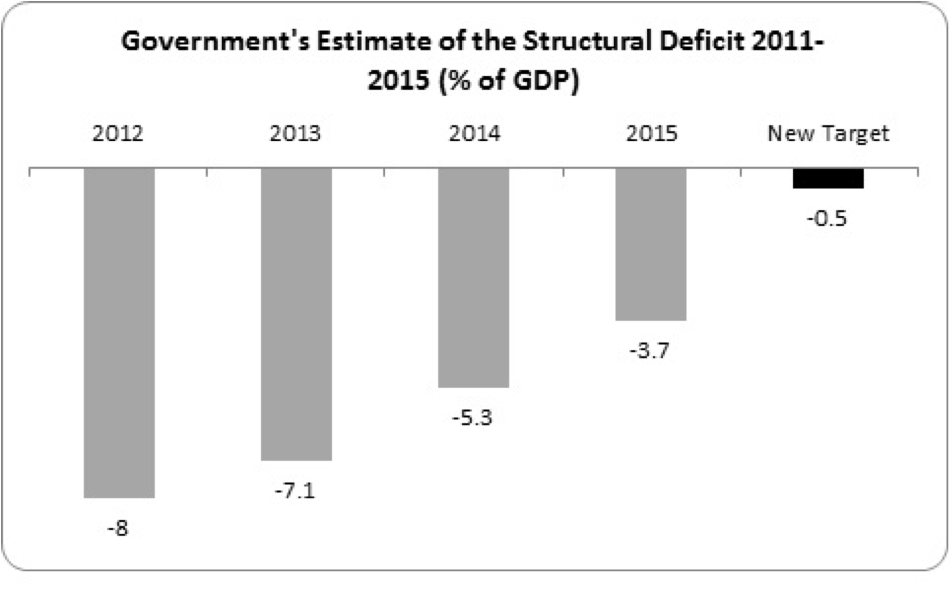

But let’s put those considerations aside for another day. Let’s take the Department of Finance’s estimate of the structural deficit up to 2015 and see how much more we would need to do to comply with this new fiscal treaty.

Even though by 2015, the Government estimates that the General Deficit will by 2.9% - thereby complying with the Maastricht guideline - this new structural deficit target in the Fiscal Treaty means that we are still deep in the woods.

What does this mean in budgetary terms? It means that the Government may have to undertake fiscal adjustments equivalent to 3.2% of GDP. In 2015, this could mean an extra set of spending cuts and tax increases worth €5.7 billion on a simple static estimate.

Under current strategy, the Government will be introducing €8.6bn in spending cuts and tax increases over the next three years. Now they are making a commitment to take on board nearly €6bn more fiscal in adjustments to reach this new structural deficit target - a 66% increase in austerity measures.

We don’t know yet when this new target will have to be met. This will be determined by the EU Commission on a country-by-country basis. It may be 2015; in all likelihood it will be later. But either way we are facing into more austerity – significantly more.

The exact amount of additional fiscal adjustment is difficult to estimate in precise numbers. That’s because the structural deficit will be determined by the EU Commission’s estimate of our potential GDP. It could actually end up being more – if the fiscal adjustments permanently reduce GDP trends. But so woolly, amorphous and erratic is this measurement, that were we to go back and ask our 10 economists for a number, you’d get 50 different answers, all replete with caveats, ifs, and buts.

But whatever numbers they did come up with, there is no question we are heading into substantially more austerity stretched out over a longer period – so much so that it might make Richard Tol’s prediction of a decade of austerity seem optimistic.

Boy, do we need a referendum. {jathumbnailoff}

Image top: mchlmbrk.