125 years on, Sherlock's still in his element

A century and a quarter on from his first print appearance Sherlock Holmes curently has not one but two new incarnations, Robert Downey Jnr in the cinema and Benedict Cumberbatch on television. While countless other fictional heroes have come and gone, Holmes has never been more popular. But the greatest mystery remains: why do so many readers fall in love with the wizard of Baker Street? By Ed O'Hare.

Question: What unites Roger Moore, Christopher Plummer, Peter Cook, Rupert Everett and Michael Caine? Answer: They are among those who have played the most portrayed fictional character ever, the world's greatest consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes. Born on the page in 1887, Sherlock Holmes has had an afterlife unlike that of any other literary creation. He is a symbol of Victorian Britain when the 'Empire' was at its height and for millions today he is as redolent of Englishness as Big Ben or Buckingham Palace. More importantly, Holmes represents intellectual brilliance and the superiority of brainpower over physical might. He is an icon of order, reason and goodness in a world grown chaotic, insane and corrupt.

Despite this, in many ways it's quite puzzling why Sherlock Holmes should be so beloved. Indeed, in theory he is among the least likeable of fictions. Holmes's mind is as dispassionate and logical as a computer and the cold, ruthless way he pursues his investigations once led him to be described as “an automaton, a calculating machine.” Arrogant and even egomaniacal, he is never afraid to boast about his mental abilities. Added to this Holmes is the archetypal obsessive-compulsive. While always immaculately dressed, his rooms, permanently choked with stale tobacco smoke, are piled high with old newspapers, letters, scientific equipment and miscellaneous paraphernalia. Were this not enough he also displays many symptoms of manic depression. When he has a case to apply himself to he seems endowed with superhuman enegy and is so consumed by it he forgets to eat. When there is no mystery to stimulate him he falls into a lethargy and resorts to a 7% solution of cocaine for distraction.

It's therefore a monument to the cleverness of the writing of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle - the Scots-Irish author who came up with the detective at the age of 28 while awaiting patients in his unsuccessful medical practice - that Holmes transcends his less appealing traits. Doyle achieved this in two ways. Firstly, he gives Holmes a great belief in justice and his efforts to discover the truth always stem as much from this as from the need to test his inductive skills. Secondly, Conan Doyle created an everyman, Dr. Watson, whose close observations of Holmes humanise him. Instead of a superman, Watson makes us see that Holmes is a brilliantly talented but flawed character, constantly battling against the more dangerous sides of his own nature.

Conan Doyle freely admitted that Holmes was not an entirely original invention. The character owed much to C. August Dupin, the aristocratic Parisian genius who lives in squalid splendour and uses his talent for ratiocination (to which he adds imaginative guesswork and criminal profiling) to solve mysteries in three tales by Edgar Allan Poe, most famously The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841). Conan Doyle also drew on some of the vivid personalities of his age. The most important of these was Dr. Joseph Bell, Conan Doyle's legendary lecturer in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, who was one of the first to develop the science of forensics and whose advice was repeatedly sought by Scotland Yard. The other was a playwright whose lightning-fast mind impressed Conan Doyle. This was Oscar Wilde.

The Sherlock Holmes stories were no overnight success. Three years passed between the sleuth's first and second appearance and only when The Sign of the Four was published in The Strand Magazine in 1890 and proved a hit was Conan Doyle was asked to write a series. In the end he wrote 56 stories and four novels featuring Holmes. Together they brought him enormous wealth, fame and a worldwide readership which has never diminished. The only person who was not enthralled with the character was Conan Doyle himself. He loathed Holmes, was dismayed by his popularity and resented how the Holmes stories far outshone the grandiose historical novels on which he laboured.

For this reason, in 1893 Conan Doyle took an unprecedented step. In the story The Final Problem he pitted Holmes against a man in every way as brilliant as himself, but with no conscience - the 'Napoleon of Crime' Professor Moriarty - and killed them both off in a duel to the death which sees the arch-enemies plummet into oblivion from the top of the Reichenbach Falls. One of the greatest villains in all literature, Moriarty appears directly only in this story but he has lain for some time like a spider at the centre of a gigantic web, ordering others to do his bidding but never acting himself - suggesting that Holmes may have unknowingly come up against him many times before. Moriarty, recently played with understated malevolence by Jared Harris in Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, had Irish origins too, as Conan Doyle partly based him on George Boole, the University College Cork mathematician whose revolutionary system of logic, the foundation of all computer programming, wowed the late 19th century intelligentsia. In coming up with an adversary for Holmes, Conan Doyle considered what would happen if a person with Boole's phenomenal gifts turned to evil, and decided that a duel could end only in their mutual destruction.

Although Conan Doyle thought this a fine way to dispose of his troublesome creation, the public was having none of it. Victorian readers were aghast, wore black arm-bands as a sign of their grief and immediately began campaigning for Holmes's resurrection. Conan Doyle held his ground for eight years, but in 1901 he brought the detective back for what is arguably his greatest adventure, The Hound of the Baskervilles. Maybe it was the promise of astronomical sums that encouraged Conan Doyle to restore Holmes to life. Maybe he missed him. Or maybe he saw the first glimmers of the unstoppable Holmes industry, the model for all the James Bond, Harry Potter and Twilight franchises, that he had inadvertently created. Conan Doyle accepted his fate, gave the public what it wanted, and they consumed it in their millions and continue to do so.

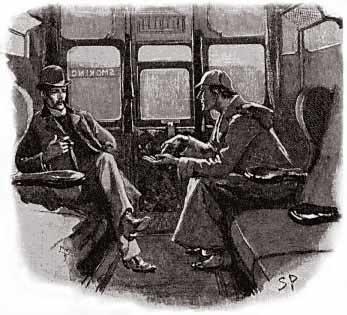

Countless movies, television series, radio dramas, stage plays, musicals, comic spoofs and even animations have been inspired by Sherlock Holmes. For many the perfect Holmes was Basil Rathbone, the South African actor who donned the Deerstalker hat and Inverness cape for fourteen movies, all produced in an amazingly short period between 1939 and 1946, despite the fact that these play extremely fast and loose with Conan Doyle's stories. Others argue that the definitive detective will always be Jeremy Brett who, alongside Edward Hardwicke as Watson, played Holmes in the lavish and faithful British television adaptations made between 1984 and 1994. The result of meticulous research (Brett studied the original Sidney Paget illustrations, and in many episodes you can see him seated in the eagle-like pose Paget gave him) and fantastic acting, Brett's Holmes, a romantic, melancholy, dark-eyed creature a mere hair's breadth away from madness, remains the performance against which all subsequent ones have been measured.

Today we are faced with two new Holmeses who are simultaneously very different and very alike. Robert Downey Jnr has managed to surprise everyone with a performance that captures all the manic energy and theatricality essential to the character while giving us a new understanding of the workings of his mind. While the more staid Holmesians may object to some aspects of Downey Jnr's performance, like his bizarre disguises, bare-knuckle boxing and use of martial arts, all of these can be found in the Conan Doyle stories and his two movies have been enjoyable escapist romps.

Benedict Cumberbatch, in the stunning new BBC series Sherlock, has dispensed with most of Holmes's surface eccentricties (he now has nicotine patches instead of a pipe), concentrating the audience's attention on the sleuth's incredible intellect but also showing us how his genius has left him isolated and estranged from ordinary life and relationships. Writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss are the first to successfully update Conan Doyle's stories, proving once more the timelessness of the character, and despite their emphasis on Holmes's instability and his status as “a high-functioning sociopath” Cumberbatch has acquired an army of female admirers.

It is thanks to these two superb actors that, 125 years after Sherlock Holmes made his first appearance, the game is still very much afoot.