An authority on evil

William Golding, the author of The Lord of the Flies, was born 100 years ago this year. A man tormented by demons both on and off the page, he was a writer with an intimate understanding of man's capacity for violence and cruelty and his brilliant and desperate novels take an uncompromising look at human evil. By Ed O'Hare.

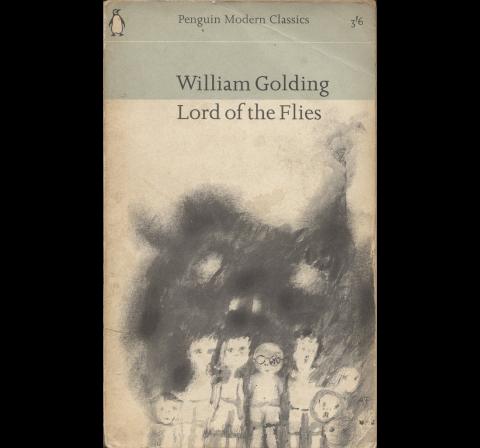

In 1954 a junior editor at the distinguished publishing house Faber & Faber thought he would take another look at a manuscript that his superior had left on the rejection pile. The book was a first novel by a middle-aged Cornish schoolmaster about a group of choirboys marooned on a tropical island. At first the boys try to replicate the structures of civilization but soon they revert to savagery. Attached to the manuscript was a note dismissing the novel as “absurd and uninteresting” and “rubbish and dull”. The junior editor, Charles Monteith, disagreed with this verdict. He saw something extraordinary in the book, which had already been rejected 21 times by different publishers, and recommended that Faber buy the rights, which they did for £60.

The story of how The Lord of the Flies, a work that frequently features near the top of many 'Greatest Novel of All Time' lists and has been translated in 30 languages, saw the light of day is by now a legend in itself. For William Golding The Lord of the Flies was a blessing, the bestselling masterpiece which transformed him from bored Classics Master into literary superhero. But it was also a curse. It became the one book Golding was immediately and permanently famous for. No matter how hard Golding tried, and he did try very hard, none of his later works could eclipse it.

This is tragic because although all of Golding's books are explorations of the same theme - man's inhumanity to man - they are much more varied and remarkable than they have sometimes been depicted. They are no mere footnote to The Lord of the Flies, but instead reflect different aspects of Golding's life, his complicated personality and his obsessions. William Gerald Golding was born in Newquay, Cornwall in 1911. When his father, also a teacher, was appointed Science Master at Marlborough Grammar School in Wiltshire the family went to live in a house close by. His mother Mildred was a housekeeper and Suffragette. As a child Golding was described as intensely, even painfully imaginative. For years he suffered from nightmares, including a recurring one about a shadowy staircase. The hallucinatory quality of Golding's fiction, and his use of strange and symbolic imagery, probably derives from his years of childhood disquiet.

Golding's father instilled in his son what he saw as the qualities appropriate to the age: atheism, rationalism, socialism and pacifism. These Golding carried with him when he went to Brasenose College Oxford in 1930. Initially a student of the natural sciences, Golding abandoned this subject two years later in favour of English literature and graduated in 1934. There followed a directionless phase, which saw Golding teach, act, play the piano and have his first flirtations with fiction. He married his wife Ann in 1939 and they had two children. This tranquil, happy period was brought to an end by the outbreak of World War II.

A volunteer in the Royal Naval Reserve, Golding eventually commanded a rocket ship during the D-Day landings, was involved in the pursuit of the Bismarck and took part in the battle of Walcheren, where his ship was the only one of the twenty four craft involved left unsunk. Golding witnessed much horror during the war and, like many servicemen, he returned to civilian life an utterly changed human being. The man who had passionately believed in human perfectability now knew better. At last Golding understood what he would write about: the undying evil that lives in the heart of man.

Golding was 43 when The Lord of the Flies was published, but he quickly made up for lost time. A sequence of novels followed which are, for their imaginative breadth and strength of vision, unsurpassed in modern literature. The Inheritors (1955) dared to suggest that the Neanderthals which preceded Homo Sapiens might have been a more gentle, empathic race than us. Pincher Martin (1956) records the last thoughts of a shipwrecked naval lieutenant as he lies adrift in the Atlantic Ocean, Free Fall (1959) investigates the loss of free will, while The Spire (1964) concerns human folly and questions of faith. A trio of novellas, essays and a stage play were also produced. Together these books confirmed Golding as a storyteller in the ancient tradition of Homer and Virgil, a fantastic synthesiser of myth, history, philosophy, comedy and tragedy.

As formidable as Golding's reputation was by the late 60s, he was not invulnerable. The poor reception of his 1967 novel The Pyramid, a claustrophobic study of life in a small English village in the 1920s, triggered a lengthy period of writer's block. Golding was prone to depression and alcoholism and for some years these seem to have held sway over him. He once claimed that he was both a “universal pessimist” and a “cosmic optimist” and his novels oscillate between joy and anguish, the wondrous and the abysmal. The 1970s saw the Vietnam War, numerous other massacres and atrocities, widespread social unrest and the first fears over the destruction of the environment. After more than a decade Golding returned with a novel that silenced those critics who doubted his ability to respond to these things. Darkness Visible (1979) has a plot that manages to combine the Blitz, miracles, terrorism, demons, paedophilia, religious fanaticism, sadomasochistic sex, nuclear annihilation and the rise of the Devil. The literary equivalent of a scream of despair, it examines every form of human evil and yet remains incredibly beautiful and moving.

Golding's follow up could not have been more different. Rites of Passage (1981) is a comic novel set in the early 19th century and follows a young aristocrat, Edmund Talbot, as he undertakes a voyage to Australia along with a ragtag collection of fellow travellers. Its popularity led Golding to write two further volumes in which Talbot completes his epic misadventure, Close Quarters (1987) and Fire Down Below (1989). Along with archaeology, horseriding, chess and orchid-growing, Golding was a keen mariner (he only gave it up after he and his family were involved in a deadly collision) and his Sea Trilogy attests to his love of sailing. In fact, the painter and sculptor Michael Ayrton once called Golding “a cross between Captain Hornblower and Saint Augustine”. Golding's final novel, The Double Tongue (1995), was a psychological tale about the Delphic Oracle and appeared two years after he died of heart failure on 19 June 1993.

It says much about the skill of William Golding that although he was the most intellectual novelist of his generation he was able to write The Lord of the Flies, a work which millions of schoolchildren have read and responded to despite his terrifying concept of man as a creature unable to escape his animality. He had seen first-hand the catastrophic consequences that result when our instinct for violence is fully unleashed and he was in no doubt that we would not survive if this happened again. He felt a personal responsibility about the fate of the planet (it was Golding who suggested the name of the Earth Goddess, Gaia, to the scientist James Lovelock) and if his prose is too cold and bleak for some this is only because of the extreme seriousness of his subjects.

Golding once remarked that “man produces evil as a bee produces honey” but the reason he could write about it with such precision was because he saw the evil in himself. He confessed that as a child “I enjoyed hurting people” and in later life described himself as “a monster in deed, word and thought”. At the same time, he knew that the only way we can start to overcome the evil within is by understanding it, and the legacy of his novels is that they have helped us to do this. They are a testament to his belief that thanks to storytelling the power of good will always win out.

Image top: scatterkeir.