Looking back: Charles Dickens, the wisdom of the heart

Charles Dicken's novels like A Christmas Carol may be much-loved classics but today's readers should not ignore the ingenuity of their social commentary nor forget that their anger at injustice was born of Dickens' own childhood deprivation. By Edward O'Hare

In 1824 a twelve year-old child started working in Warren's boot blacking factory at Hungerford Stairs near modern day Charing Cross. For ten hours a day the boy stuck labels on bottles of shoe polish. It was monotonous and poorly-rewarded drudgery. The factory was a foul place and he was often brutally treated. At the end of the day he wandered back to filthy lodgings where he snatched what little sleep he could before the whole grim cycle began again. The pitiful money the boy earned went to pay off the substantial debts of his father who, along with the rest of the family, had been sent to live in Marshalsea Debtor's Prison. The experience shaped the imagination of the man who became the most successful novelist of his time and one of the greatest storytellers of any age, Charles Dickens.

Today's literary critics agree that preaching is the cardinal sin any novelist can commit. Fiction writers may tell us about morally dubious practices but they have no right to condemn them. The reader should always be left to decide what their own moral position is. Dickens would have scorned this argument as balderdash. He was one of the most socially engaged of all fiction writers and believed that the novel could be a powerful instrument for change. While it's true that most writers who have held this viewpoint produced turgid and unconvincing work, this can hardly be said of Dickens. His immense conscience was matched by an epic imagination, arguably the greatest since Shakespeare's, which allowed him to create works which exposed the evils and inequalities of his age and which speak to each new generation.

By the time Dickens left the boot-blacking factory he had received little formal education and his prospects were bleak. His wide reading won him a job as a law office clerk and in his spare-time he learnt shorthand which allowed him to make a break for freedom when he became a freelance reporter early in the 1830s. Patient knocking on doors led to the publication of his first full-length novel, The Pickwick Papers, in 1836. A huge hit, it gave Dickens a global audience and launched his extraordinary career. But this was not enough. Dickens considered himself incredibly lucky to have escaped the clutches of poverty and he strived to improve society so that others would not have to suffer the horrors and indignities he had.

Looking at Dickens life it's hard to fathom how he fitted so much into 58 years. Aside from producing a succession of novels, all of them masterpieces of English literature, he channelled his prodigious energy into a wealth of other projects, many of which would have been work enough for any ordinary individual. Dickens was the proprietor of two weekly journals, wrote and edited essays on hundreds of different topics, acted on the stage and gave hugely popular readings and travelled extensively, visiting America, Canada and even Ireland. However, his campaign for social reform was his consuming passion. In a relentless series of pamphlets and articles he made known the plight of the poor, the neglected and the forgotten. He called for an end to child labour and debtors prisons and demanded improved conditions in workhouses, more opportunities for underprivileged young people and the abolition of slavery.

Dickens also took more direct action. In 1846 the heiress of a banking fortune Angela Burdett Coutts asked him to assist her in establishing a home for fallen women. Dickens threw himself into the project with gusto. He found a suitable location for the institution, which became known as Urania Cottage, in modern-day Shepherds Bush. Here young prostitutes were treated with kindness and given the skills that would allow them to build better lives. Dickens was involved in every aspect of the daily running of Urania Cottage and even interviewed prospective entrants. Another institution which benefited from his tireless labour was Great Ormond Street Children's hospital. It was through a charitable appeal organised by Dickens that the hospital not only survived its early years but was able to buy an adjoining building, more than trebling the number of patients that could be treated.

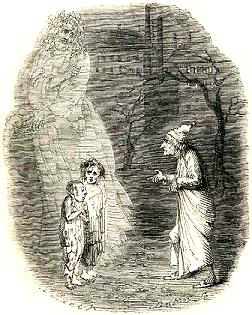

Dickens works are beguiling combinations of literary styles. He was a master of social realism, picaresque adventure, farce, satire, gothic grotesquery and fable but his novels are defined more than anything by his blatant hatred of oppression and hypocrisy. The symbolic characters Dickens used to make his point are simple but enormously effective. Take David Copperfield's Mr. Micawber who never loses faith that "something will turn up" and allow him to better himself, the noble-hearted convict Abel Magwitch in Great Expectations, the orphans living rat-like in Fagin's den in Oliver Twist or the endless machinations of the draconian legal system which keep the vast cast of Bleak House, a work which rivals Ulysses as the greatest novel in the English language, in a state of living death. Even A Christmas Carol contains some very powerful imagery, like the self-created chains that bind the spectre of the miser Jacob Marley, the ghastly emaciated children Ignorance and Want who lie hidden beneath the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present or the skies of London swarming with the tortured spirits of the unhappy dead destined to perpetually wander the earth.

Dickens works are beguiling combinations of literary styles. He was a master of social realism, picaresque adventure, farce, satire, gothic grotesquery and fable but his novels are defined more than anything by his blatant hatred of oppression and hypocrisy. The symbolic characters Dickens used to make his point are simple but enormously effective. Take David Copperfield's Mr. Micawber who never loses faith that "something will turn up" and allow him to better himself, the noble-hearted convict Abel Magwitch in Great Expectations, the orphans living rat-like in Fagin's den in Oliver Twist or the endless machinations of the draconian legal system which keep the vast cast of Bleak House, a work which rivals Ulysses as the greatest novel in the English language, in a state of living death. Even A Christmas Carol contains some very powerful imagery, like the self-created chains that bind the spectre of the miser Jacob Marley, the ghastly emaciated children Ignorance and Want who lie hidden beneath the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present or the skies of London swarming with the tortured spirits of the unhappy dead destined to perpetually wander the earth.

By his death in 1870 Dickens had done more than any politician to make the upper classes understand that the poor were not animals but people. His works are often attacked for their supposed sentimentality but he was no victim of nostalgia. It was the progress of humanity, right down to the last individual, that concerned him. As G.K. Chesterton once said, Dickens greatest attribute was that his books "encouraged anybody to be anything". What some mistake for sentimentality is the illimitable enthusiasm and compassion of a man who dared his readers to image a better future.