The challenge of playing Beckett

Michael Gambon’s performance in Krapp’s Last Tape is a reminder that, just like any other playwright, it is the performances of great actors that give his words life. Politico looks back at the many talents who have risen to the challenge of playing Beckett. By Edward O’Hare.

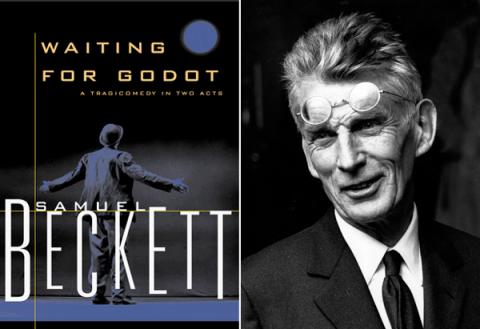

In December 1957 Samuel Beckett tuned in his radio to hear a broadcast of his novel Molloy on the BBC. What he heard unnerved him. Reading Molloy was the Irish actor Patrick Magee whose distinctive tones were exactly those of the voice he had heard inside his head when composing the novel.

Beckett was delighted that his first collaboration with an Irish actor had been a success and so inspired was he with Magee’s “wheezy ruined old voice” that within weeks he had written the first draft of a monologue that would become one of his greatest plays, Krapp’s Last Tape.

Beckett’s attitude to his work has been depicted as controlling, even tyrannical. Everyone has heard how he once admonished an actor for pausing for a second too long and told others to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

What undermines this imperious conception of Beckett is that his relationships with actors were always conducted on equal terms and were often extremely close. Beckett had a very definite imaginative vision but he knew that this had to be interpreted by actors. He liked nothing better than performers who pored over the text as meticulously as he did in search of unusual angles, and who injected their personalities into their characterizations of his tramps, invalids and outcasts.

Only when this happened did Beckett’s work, to use his own words, ‘sing.’

Over two decades Beckett directed 16 of his plays and involved himself with many more. This brought him into contact with a diverse collection of actors, many of whom became personal friends. On the set of the definitive 1964 production of Endgame Beckett made the acquaintance of Magee along with the Rathmines-born Jack MacGowran.

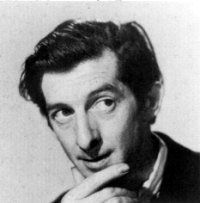

Stocky, white haired and with piercing eyes, Magee found a perfect acting counterpart in the clownish, bird-like MacGowran. Originally from Armagh, he spent years as a travelling player before becoming an unlikely star through his association with Beckett.

Stocky, white haired and with piercing eyes, Magee found a perfect acting counterpart in the clownish, bird-like MacGowran. Originally from Armagh, he spent years as a travelling player before becoming an unlikely star through his association with Beckett.

According to Beckett’s biographer James Knowlson, the playwright admired the duo because instead of looking for symbols in his plays they strived to find an acting style that suited the piece. Their hard work was rewarded and Knowlson writes that Beckett, always partial to a drop, was in good company with the ‘awe-inspiring’ drinkers Magee and MacGowran.

(Picture: Jack MacGowran)

There was an evening of raucous boozing in a pub near Piccadilly when Beckett, Harold Pinter and Magee discussed the Marquis de Sade. By the time the play opened the gang had whistled up what Knowlson describes as ‘a hurricane of sustained heavy drinking’ and even Beckett considered himself lucky to be ‘still on my feet.’

Jack MacGowran emerged as the archetypal Beckett actor. From his haunted eyes and haggard features to his elegant gestures and rich voice, he had all the requisite qualities. Over five years he worked tirelessly on Beginning to End, a one man show of Beckett.

Although the experience left MacGowran ‘shattered’ the ‘rewards were tremendous.’ For him Beckett was the poet of ’human distress, not despair’ and he considered him a writer who had ‘so much compassion for the human race’ and whose work ’always ended with hope.’ MacGowran’s anthology played to audiences the world over and when Beckett’s centenary was celebrated it was the screening of RTE’s recording of it that for many people stood out as the highlight.

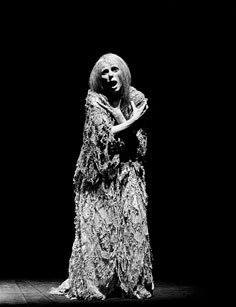

Female interpreters of Beckett have the hardest time of all. When not buried up to their waists in sand, encased in giant urns or dustbins or suspended above the stage with only their mouths visible, the demands are manifold. The finest actress Beckett ever encountered was Billie Whitelaw.

Tall and powerful, Beckett immediately took Whitelaw under his wing. Their relationship was so passionate that to many it had the appearance of romance. Originally confused by Beckett’s one request, ‘no acting,’ Whitelaw soon realised that what he meant was to ‘keep out of the way of the life the part starts to have.’ She would annotate her script with code words that looked like nonsense. Despite the stressful rehearsals Whitelaw established herself as the great Beckett actress and created several of his characters, most notably the part of May in Footfalls.

Tall and powerful, Beckett immediately took Whitelaw under his wing. Their relationship was so passionate that to many it had the appearance of romance. Originally confused by Beckett’s one request, ‘no acting,’ Whitelaw soon realised that what he meant was to ‘keep out of the way of the life the part starts to have.’ She would annotate her script with code words that looked like nonsense. Despite the stressful rehearsals Whitelaw established herself as the great Beckett actress and created several of his characters, most notably the part of May in Footfalls.

(Picture: Billie Whitelaw)

Today it would probably amaze Beckett to learn of the calibre of performers his work attracts. 2000’s Beckett On Film project saw some of the world’s biggest acting talents take on his signature roles.

Barry McGovern has developed I’ll Go On, his own internationally acclaimed one man show based on Beckett’s works. The Gate Theatre has continued to bring on board major names for its Beckett productions, and Michael Gambon’s turn as Krapp illustrates just how important doing Beckett has become for an actor.

But what we should remember when we go to see this production is that Beckett himself was a connoisseur of real acting and even wanted to be an actor himself in his early life. The process of directing fascinated him because it allowed him to give others the kind of experience that he enjoyed so much himself. His collaborations with actors were opportunities to correct what he saw as the mistakes in his work and come to a fuller understanding of himself and his art.