Judging Lemass - States of Ireland

Below is an extract from the first chapter of Judging Lemass, published by the Royal Irish Academy.

Interview with Ken Whitaker, Secretary of Dept of Finance under Sean Lemass

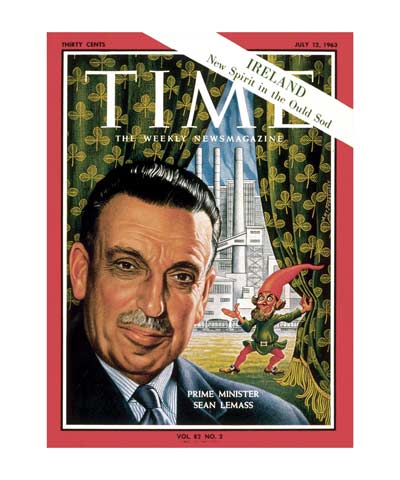

Profile of Sean Lemass written by Vincent Browne for Nusight in 1969

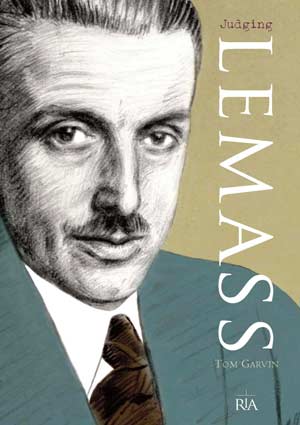

On 14 January 1965 the young son of the secretary of the Department of Finance informed his father that there was a big policeman at the gate of their house on the Stillorgan Road, near Donnybrook in the south suburbs of Dublin. Perhaps he wondered what Daddy had done. T.K. Whitaker was among the few people who knew what the Garda was there for, and went out to meet Sean Lemass, Taoiseach and leader of the Fianna Fail party, in his Gardaadriven prime-ministerial Mercedes-Benz. Whitaker got into the car, and the Taoiseach greeted his senior civil service official and informal advisor on Northern Ireland. Lemass growled at the driver, 'Henry: Belfast!' Lemass did not even tell Kathleen, his wife of 40 years, where he was going that morning; that way, things could be kept quiet for a bit longer. However, Henry Sheridan, the Taoiseach's Garda driver since 1961, remarked to his wife, Evelyn, the night before that he had been told to prepare for a long day's drive, and it occurred to both of them that it involved a visit either to an agrarian outbreak in the midlands or possibly to Northern Ireland. Henry fuelled the car up in anticipation. Evelyn intuited the North; it must have been in the air, somehow.

On the way to Northern Ireland, Lemass, not a great man for small talk and rather given to long silences unless there was evidently something necessary and germane to be said, treated Whitaker to an impromptu seminar on the virtues of the American Constitution of 1789, emphasising the unique system of separaation of powers, federalism and judicial review that characterises that classic document of political architecture;' Presumably, federalism was on his mind yet again; over the years he had taken an interest in federal devices as they worked elsewhere in the democratic world. The car paused on the Republic's side of the border for some minutes so as not to arrive too early; Lemass was a stickler for punctuality: be neither early nor late. To his mind, to be early could cause embarrassment, to be late was insulting.? The party duly crossed the frontier, and Jim Malley, ex-Spitfire pilot and private secretary to Terence O'Neill, prime minister of Northern Ireland, met them at the British customs post outside Newry, as arranged. On the second leg of the journey to Stormont, this one with a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) motorcycle escort, the small talk was about poker, a passion of I.ernass's." Malley was fascinated by Lemass, apparently almost as though he were some exotic creature. He described him as 'a most extraordinary man'.

Someone in Cabinet in Dublin had leaked the information about the projected visit to the Irish Times, and the paper had despatched a cameraman to the border to snap the historic occasion." This may be how Mrs Sheridan correctly guessed the destination of the journey, even though an off1cial blanket of secrecy had covered the operation. Perhaps there was no connecction, but there was a well-established tradition even then of leaks from Charles Haughey, an up-and-coming young TD and minister, who was also Lemass's son-in-law, to John Healy, political correspondent of the Irish Times.

Above: Terence O’Neill and Lemass walking in the grounds of Stormont House following their historic meeting, 14 January 1965. Behind them from left to right are Ken Bloomfield, senior officer in the Northern Ireland civil service; Cecil Bateman; and T.K. Whitaker, secretary, Department of Finance. (Courtesy of Ken Bloomfield)

On arrival at Stormont, O'Neill welcomed Lemass with the carefully phrased greeting 'Welcome to the North', thereby avoiding the possibly taboo words 'Northern Ireland' and 'Ulster'. Lemass did not reply, increassing O'Neill's unease. He suggested that the Taoiseach might wish to wash his hands after what was such a long journey by the Irish standards of that time, and a far longer one politically than geographically. There seems to have been a prolonged and somewhat uneasy silence as the two men walked to the toilets. O'Neill reminisced:

Eventually, in the rather spacious 100 at Stormont House he suddenly said, 'I shall get into terrible trouble for this.' 'No, Mr. Lemass,' I replied, 'it is I who will get into trouble for this.' I then took him into the drawing room and introduced him to my wife and Cecil Bateman and Ken Bloomfield of the Cabinet Off1ce staff From then on he thawed out and became a very pleasant and amusing guest.

The conversation was quite free, even somewhat politically incorrect. At one early stage one of the northerners, to break the ice, remarked that he personally regretted that the partition of 1920 had not included the westtUlster county of Donegal; it would have rounded off Northern Ireland nicely, he felt. Perhaps he also thought a shorter border might have been a good thing: easier to patrol. Lemass riposted humorously that they were welcome to Donegal, as long as they took Neil Blaney, a rather rambuncctious and very anti-partitionist Fianna Fail politician in that county, with it'? Even Lemass seems to have had trouble with Blaney, who was quite a firebrand. Some years later, under Taoiseach Jack Lynch, a quiet Corkman who lacked I.ernass's authoritativeness, Blaney, as a senior minister in the Irish government, was to publicly call O'Neill a 'bigot', which he quite transparently was not." Blaney was to get away with it, and would not have done so under Lemass; Lynch lacked Lemass's revolutionary pedigree. However, back in January 1965 the northerners seem to have been somewhat surprised by Lemass, possibly expecting some wild-eyed revoluutionary. One of them thought that the southerner, always a sharp dresser, had a 'gangster's suit':" but then, in southern eyes, northerners dressed square. Ken Bloomfield, a senior officer in the Northern Ireland civil service and therefore Whitaker's opposite number, thought Lemass at first sight had a rough charm:

The taoiseach was burly, leonine and gruff, like some veteran French politician of the left. He spoke with a delicious growl. When O'Neill asked him if he knew well the then leader of the [British Conservative] Opposition, Alec Douglas-Hume, he confessed he had always 'had some reservations about the innate capacity of the Fourteenth Earl'.

North-South rapprochement had been in the air for some time, and the end of the IRA 'Operation Harvest' campaign in 1962 offered a window of opportunity. The possibility of North-South co-operation in a number of important areas, in particular transport and electric power (including nuclear energy), was mooted at a meeting between Lemass and Harold Wilson on 16 March 1964. Wilson was leader of the opposition at the time but was expected to become prime minister of the UK shortly. Long before the Belfast meeting, O'Neill acknowledged Whitaker's role in taking the initiative. He remarked to Tony Grey of the Irish Times that he had once told Whitaker that ifhe ever replaced Lord Brookeborough as prime minister, he wanted a meeting with Lemass to be arranged.!' The immediate preparaations for the meeting went back to an encounter on a liner bound for the us. Whitaker had met Malley on board ship while he was en route to a meeting of the International Monetary Fund in Washington. Both had agreed to sound out their bosses back home about the possibility of a meeting between the two prime ministcrs.F Lemass jumped at the idea. Whitaker remembered:

I knew O'Neill for a good while before the visit, that is why I was the channel for the invitation. The quickness of I.ernass's response was notable. I had to remind him it might be an idea to have a word with [Minister for Foreign MfairsJ Frank Aiken. 'I suppose so', he said, and rang him straight away. Aiken was a bit taken aback but fairly quickly agreed.13

O'Neill, although uneasy about his backbenchers, was also receptive, much to the surprise of some southern leaders, accustomed as they were to northern obduracy; O'Neill, an enlightened, if not always effectual, politician, was actively seeking to open doors between the two Irish states. Eventually, a note arrived from O'Neill through Malley and Whitaker that amounted to an innvitation.

The meeting was a leap of faith for both men, and a brave one, particcularly for O'Neill, who was in a much weaker position domestically. Lemass held the better hand, poker player that he was, but even he was taking an enormous gamble, and was trying to transcend or bypass a considerable amount of remembered history, bitterness and political passion. Admittedly, he had the advantage of being the prime minister of a sovereign country, and was also the undisputed leader of a highly organised political party, Fianna Fail, a dominant party that he had played a major part in creating in the 1920s. He had recently inherited the leadership of the party from Eamon de Valera, legendary leader of Irish republican nationalism. O'Neill, by contrast, was the premier of a devolved government in a province of the UK, a province whose majority population had a collective psychology of siege and whose ruling Unionist Party was internally troubled. Furthermore, the Taoiseach had not only a united political party but also a consensual population behind him, whereas the North itself was riven, and within O'Neill's own party itself there were deep divisions and even hatreds behind the apparently monolithic front of Ulster Unionism. Eventually, this cirrcumstance was to destroy O'Neill.

However, in 1965, this was all still in the future, and Lemass was exhibitting a considerable amount of empathy and political creativity. He came from a nationalist revolutionary tradition that had deep roots in Ireland; his family had a background of Dublin Parnellite politics, and there was a long family tradition of puritan hard work and successful artisanal and business enterrprise. The militant Volunteer movement, a movement that culminated in the 1916 Rising and the ensuing struggle for independence, had swept up Lemass himself as a youth. However, as argued later in this book, his Parnellite and relatively liberal background seems to have set him apart from many of his Sinn Fcin-c--later, Fianna Fail-comrades. They tended to be bewildered by his pragmatism, his religious agnosticism, his disregard for many widely held orthodoxies and his mainly unspoken but quite obvious disregard for rural ways and society. Some were shocked by his lack of interest in the massive attempts of the new state to revive the Irish language as the spoken vernacular of the Irish people. He accepted the Irish-revival business as a means of boosting morale, always an obsession of his, but had to force himself to relearn it at the avuncular urging of de Valera. He was about to do something else unexpected: as prime minister and political heir to the rigidly anti-partitionist de Valera, he was, in effect, to recognise Northern Ireland. However, to placate northern nationalist feeling and to ensure that the northern minority did not feel that it was being sold out, he had to deny the reality of what he was doing. He was only partially successful. An aging man in his mid-60s and nearing the end of his political career, he possibly felt that it was time to clear up the unfinished business in the North, business he evidently felt to be irrelevant to the future of Ireland and damaging to the island's general developmental prospects.

By the mid-1960s, the Irish cold war over partition and the disputes over the legitimacy of both Irish political entities had been going on, in one form or another, for over 40 years; Ireland had been partitioned by a British act of parliament in 1920 in the middle of the Irish War of Independence. For many Irish people in both parts of Ireland, the right to rule of the Stormont government was illegitimate; Republicans were fond of pointing out that no one in Ireland had voted for what they termed the 'Partition Act' of 1920. In the eyes of a significant and passionate Republican minority, the legitimacy of the new Irish Free State government of 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921-2 was almost equally suspect. In the South a vicious little civil war had been fought between those who insisted on the continuing sovereignty of the half-imaginary Irish Republic declared in 1916 and 1919 and those who accepted the compromise Treaty of 1921 as the best deal that could be attained, a deal that could be improved upon peaceably in future. The pro-Treaty 'Free State' side easily won both the military conflict and the 26-county elections of June 1922 and August 1923. For a year afterward, Irish Army soldiers were posted outside exxUnionist farmhouses in west Cork and elsewhere to ensure that no more 'burning out' happened. De Valera, putative leader of the Republican side but actually a virtual prisoner of the Republican diehards, declared that the Free State government was illegitimate and alleged that the Treaty had been signed under duress. Privately, he knew that the electorate was overwhelmmingly against him and his political stance. He also must have gradually realised that the British could not wait to get out of 'Southern Ireland', as the Tommies, the Auxies and the Tans disappeared and the disbanded and pensioned-off Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) left their barracks for looters to strip all over the 26-county area.

De Valera gradually drew certain political conclusions during the years 1923-6, some of them almost certainly prompted by sharp comments from Lemass. One was that nothing could be achieved through violence; another was that the way to power in Ireland was through the heart of the Irish voter. This second lesson he never forgot. In the short run, he set to creating a 'let's pretend' imaginary Republican administration, employing fellow antiiTreatyite leaders, among them a very young Sean Lemass. He held on to the control of American money in his capacity as 'President of the Irish Republic', even though he had been deposed by vote of the Second Dail in January 1922 in favour of Arthur Griff1th, the founder of the original Sinn Fein party back in 1904; Griffith was president of the Irish Republic from January through to the time of his death in August 1922. A few years later, de Valera formed, on the advice and urging of Lemass in particular, Fianna Fail, a party that went on to be what political scientists term the natural governing party of the Irish state. De Valera's phenomenal charisma and I.emass's organisational energy eventually made Fianna Fail an unprecedenttedly successful Irish popular political entity. Lemass set to the apparently Sisyphean task of modernising and industrialising the agrarian Irish economy as minister for industry and commerce in the Fianna Fail governnments of 1932 onward.

In the North hideous pogroms between Catholics and Protestants acccompanied the establishment of the northern state, resulting in Northern Ireland becoming a Unionist-dominated province within the UK. The northern polity became very much at odds with an increasingly nationalist and anti-partitionist Dublin state dominated eventually by de Valera and the Catholic Church to the south and west of Northern Ireland. In both jurissdictions religious minorities were subject to political subordination and discrimination. However, discrimination against Protestants in the South, although nasty, was minor compared with the wholesale discrimination against Catholics that occurred in the North. Furthermore, discrimination against the other guy was traditional in both parts of Ireland and on both sides of the religious fence. Another difference was that in the South there was a religiously instigated and extralegal attempt to marry Protestants out of existence, whereas in the North discrimination was more clearly state-driven.

In the South an anti-partitionist orthodoxy that laid claim to the North as the stolen and sundered 'Six Counties' became almost universally accepted. This irredentist mentality seemed at times to justify military action against what was seen as the Protestant and British local majority tyranny in the North. Even moderate opinion saw partition as evil and as an injustice, and it was blamed for Irish economic woes. In the North the siege mentality was reinforced by these developments, and the intransigence of Dublin also encouraged some northern Catholics not to engage with the northern regime. Catholics in Northern Ireland came to see the South as a Prester John country, hoping against hope that eventually the southerners would come to rescue them from their predicament. When Dublin behaved cautiously and moderately, it was seen by some as betrayal and sell-out.

Partition endured. It was reinforced mightily by Republican impossibillism after January 1922. More importantly, it was strengthened by the fact that Ulster, the northern province ofIreland, had, long before 1920, shown clear signs of developing in very different directions from the other three more agricultural and semi-feudal provinces on the island. This divergence occurred despite the existence of a common administrative system, good all-island communications and a compact geographical environment that both entities shared. The divergence also occurred in spite ofIreland's long existence as a cultural entity and even defied the existence of island-wide Protestant and Catholic ecclesiastical organisations, which were organised on a 32-county, all-Ireland basis. For a long time, even the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland sat in Dublin rather than Belfast. Gaelic football and hurling were still organised on an all-Ireland basis after partition, as were international and domestic rugby. However, partition did have the effect of setting up two' countries' in Ireland, to some extent reflected in two sets of social organisations. Two farming organisations emerged, and eventually there were two soccer teams for international purposes. Oddest of all, perhaps, were the three sets of cycling teams-one all-Ireland, one for Northern Ireland and one for the 26 counties only.

Partition therefore accelerated or aggravated a process of divergence that had previously existed, and did not artificially instigate it for the first time. Ulster was the only Irish province where a large British, non-Catholic poppulation put down deep roots and became a settled and large community. The Ulster plantations of 1607 onwards were mainly Scots and English Borders in origin, and they proved very successful, while remaining culturally distinct from the majority ofIrish people elsewhere on the island. Long before planntation, Antrim and Down had had intimate contact across the North Channel with south-western Scotland, the sea behaving as much as a large river as an arm of the sea. These contacts had prehistoric precedents, and in the first millennium, in Gaelic times, a joint eastern Ulster and western Scotland kingdom of Dal Riada had flourished, ruled from its citadel at Dumbarton in Scotland. Even under landlordism, there had been the Ulster Custom, which rewarded tenants for improvements to their agrarian holdings, a proviso that did not exist in the other three provinces, where landlords and tenants were divided not only by religion but also by a land law that was highly exploitative. Again, the nine-county Ulster of British times was divided roughly half-and-half between Catholics and Protestants, the latter being mostly Presbyterians, whereas down in the South most Protestants were Church of Ireland, rather than Presbyterian, and were in a minority of well under 10%. Also, Ulster Protestants tended to be members of a large and classic Victorian working-class community, unlike their southern co-religionists, who were of all class backgrounds, with some bias towards relative wealth and privilege.

Partition therefore accelerated or aggravated a process of divergence that had previously existed, and did not artificially instigate it for the first time. Ulster was the only Irish province where a large British, non-Catholic poppulation put down deep roots and became a settled and large community. The Ulster plantations of 1607 onwards were mainly Scots and English Borders in origin, and they proved very successful, while remaining culturally distinct from the majority ofIrish people elsewhere on the island. Long before planntation, Antrim and Down had had intimate contact across the North Channel with south-western Scotland, the sea behaving as much as a large river as an arm of the sea. These contacts had prehistoric precedents, and in the first millennium, in Gaelic times, a joint eastern Ulster and western Scotland kingdom of Dal Riada had flourished, ruled from its citadel at Dumbarton in Scotland. Even under landlordism, there had been the Ulster Custom, which rewarded tenants for improvements to their agrarian holdings, a proviso that did not exist in the other three provinces, where landlords and tenants were divided not only by religion but also by a land law that was highly exploitative. Again, the nine-county Ulster of British times was divided roughly half-and-half between Catholics and Protestants, the latter being mostly Presbyterians, whereas down in the South most Protestants were Church of Ireland, rather than Presbyterian, and were in a minority of well under 10%. Also, Ulster Protestants tended to be members of a large and classic Victorian working-class community, unlike their southern co-religionists, who were of all class backgrounds, with some bias towards relative wealth and privilege.

North and South, different before 1920, became more different afterrwards because of their very different political histories, and have developed noticeably different identities. Within each area, the populations, simply by living together, have come to share common identities that exclude those outside for certain purposes. Protestants and Catholics in the North tended to see themselves as having much in common, much that was not shared by either the inhabitants of the Republic or by the peoples of Great Britain, even if what was shared often amounted only to an awareness of a common predicarnent.!" Similarly, the people of the Republic came to see northerners as 'different', largely because they did not share the experience of independdence, civil war and neutrality during the Second World War; nor did the northerners share the political education forced upon southerners by soverreignty. In particular, economic development, or the lack thereof, was a chronic obsession of southern leaders and of southern political debate, but northern development was really a concern of London. The South had sat out the Second World War as a terrified bystander, whereas northerners had participated openly in the battle for Britain's survival against Naziism. Men from both parts of Ireland fought on a volunteer basis in the ranks of the British forces, but southerners tended to keep quiet about it afterwards. Roughly equal absolute numbers of volunteers from both areas served. Oddly, five of the six Victoria Crosses awarded to Irishmen during the Second World War were won by southerners. All six were Catholics; the Irish situation was full of such iron ies.l ' Paddy Finucane, a well-known Spitfire ace of the Battle of Britain who shot down five German planes and was killed over France in 1941, was the son of a man who had been' out' in the Easter Rising. Southern Protestants threw in their lot with the new state and often became enthusiastic participants in democratic politics, opinion forming, the armed forces and public office, to an extent not generally possible for Catholics in the northern sub-polity. By and large, the inhabiitants of the Republic forgot British rule, whereas northerners were always aware of it, Southerners thought rarely about the North, and to many northherners the South eventually became a picturesque irrelevance; to both, London remained for a long time the local Weltstadt, accepted by the Irish, at the assessment of that city's own inhabitants, as being the capital of the world. Confusingly, when any set ofIrish, northerners or southerners, went to London, they were all lumped together by the uncaring English as 'Paddies', much to the annoyance of Unionists. To some northerners, southherners talked fast and thought slow; to some southerners, northerners were over-obsessed with each other. Despite having sympathy for the plight of northern Catholics, southerners for a long time envied northerners their higher standard ofliving, generated in part by the generous provisions of the British welfare state during the first decades after the Second World War. The southerners had a liking for the English that was in part derived from a feeling of equality with them; independence eventually eliminated the ancient sense of subordination. The opening up of Europe in the 1950s and the visit of John F. Kennedy to the Republic in 1963 intensified a sense in the Republic that the state had somehow arrived and that its post-war relative isolation was over. Northerners knew their destinies were controlled by a British government that was, if not exactly foreign, remote from both northern clans, geographically and psychologically. Again, the welfare state developed later, and in a rather different way, in the South.

Like Spain and Portugal, or the partitioned German states during the period 1949-90, the two Irelands attempted to ignore each other, while at the same time being forced by propinquity and the interweaving of so many institutions and geographical facts of life to co-operate with each other. The Republic, which, after all, is not just the south of Ireland but all of the west and the lion's share of the east as well, came to pretend that it was Ireland tout court, while the North tried to represent the boundary between itself and the rest of the island as a wholly natural, obvious one with the immediate physical immediacy of a range of mountains or an arm of the sea. The North commonly labelled the Republic a 'foreign country', to unintended comic effect. For good measure, the Republic denied symbolic recognition to Northern Ireland and occasionally pretended that Great Britain was as remote and unfamiliar a country as Outer Mongolia. Even practical measures of coooperation, such as joint authority over the Foyle fisheries, the cross-border services of the Great Northern Railway bus and rail transport concern or the hydroelectric works on the Erne waters, took place quietly and without any public political rhetoric. Informal extradition ofIRA suspects often occurred, suspects being handed quietly over from one jurisdiction to the other, commonly under cover of darkness at unfrequented border crossings. Eventually, this was ruled illegal by southern courts, but the two police forces quietly exchanged information quite frequently, when it was politically feasible. Top-level conferring, as distinct from extensive low-level co-operation, seems to have virtually never taken place between 1932 and the mid-1960s, an extraordinary circumstance in a compact island inhabited at that time by 4 million people. All of this made the official encounter of January 1965 of great symbolic and psychological importance.

Brief encounter: the thaw

In the 1950s and l%Os things had been changing: the influence of the mass media; of the relative, if partial, arrival of affluence; the coming of television and the impact of Vatican II on Irish Catholic 'group-think' had begun to erode the irredentist political orthodoxy created by de Valera and his ideoologues. In the mid-1950s, voices were raised in the Republic against the doctrine of the 'Indivisible Island', and qualified defences of the Unionist tradition in Ireland were articulated by people of nationalist background, as distinct from contributors to the ex-Unionist Dublin Irish Times. 17 This paper always expressed a qualified sympathy with Ulster Unionism. The official antiipartitionist orthodoxy was more or less intact even as late as 1968-71, when the northern crisis erupted, but it had always had a certain flimsy, artificial and unpopular character to it, and only a passionate minority really took it seriously. Like so many of de Valera's doctrinal devices, it was designed to win votes at the margin of the electorate rather than to be a genuine attempt to unnderstand everyday reality. As Lemass was wont to say privately, no one with any sense believes election promises. However, he also remarked once, 'the art of political propaganda is to say what most of the people are thinking' .18 Patrick Hillery reminisced:

[Lemass] on the North: there was a Parliamentary party meeting some time in '57-'59, after we had come back into government. The IRA campaign was on, and a lot of people were coming under pressure in the constituencies, as I was. Dev had called the meeting to pull things into line. At one stage a speaker suggested that 'peaceful means had failed'. Lemass was quick to respond, arguing strongly that 'peaceful means never got a chance'. He instanced a number of occasions over the years where possibilities had been missed; suggested it was almost as if Brookborough [sic] was in charge of the IRA-every time it looked as if we were gaining an advantage, the IRA would be summoned into action and everything would be jeopardised again.

Lemass latched on to the European idea early, and in the 1950s 'Europe' started to become a concrete reality. As Taoiseach in 1961, he felt able to comment in almost traditional terms on the supremacy of political considderations over economic considerations:

It would be a great error to underestimate the extent to which the full execution of the formal obligations of the Treaty [of Rome], even though they bear on economic matters, can affect the powers exercised by individual governments in a political sense, as this expression is generally understood. It is not believed [by the government] that political unity will grow, automatically, from economic unity; rather it is believed that it is only on the basis of political agreement that a permanent solution of the economic problems can be founded."

Northern Unionists began to see him as someone who was less 'imposssible' than de Valera or even his younger fellow politicians in Fianna Fail. Unlike many of his colleagues, Lemass saw through the absurdity of this self-defeating little cold war conducted by megaphone diplomacy. Northerners whom he trusted helped him evolve a very revisionist stance on partition. Whitaker was a later influence on him, as was Donal Barrington. Another informant was possibly an unexpected one: Ernest Blythe, northherner, Protestant, Cumann na nGaedheal minister for finance in the first Free State government and well-informed critic of southern attitudes towards the North. Blythe was also hated by Republicans for his rather bloodthirsty attitudes towards anti-government rebels in 1922-3. He had also been heavily involved in the acceptance of the existing partition line in 1925 in return for certain financial considerations, and famously termed it at the time 'a damned good bargain'. The Republicans, naturally, declared it to be another sell-out. In 1962 Blythe and Lemass corresponded with each other, and Blythe gave the Taoiseach a crash course in northern realities; sectarianism was a given in Northern Irish politics, he told Lemass. Dublin's posture of non-recognition, a posture that dated from 1937 rather than 1922 and was de Valera's creation, only made things worse. Dublin should unequivocally recognise the Northern Ireland regime, drop non-recognition completely and engage in free and equal co-operative policies. He went so far as to argue that the aggressive southern non-recognition of Northern Ireland, devised by de Valera in the 1930s to placate his IRA veterans, was the cause of northern sectarian politics, an argument that flies in the face of the matter-of-fact acceptance by WT. Cosgrave's Dublin government of the northern refusal to come in to the Free State in late 1922. It also ignores the long resistance to Home Rule and the violent hostility to Catholic rights that characterised so much of Ulster politics dating back to the early nineeteenth century. However, Blythe insisted quite cogently that any aggressive political action against Ulster Unionism was self-defeating and foolish:

If at an early date we find ourselves able to abandon hostility and attempts at pressure, then even the Northern Nationalist party, which depends for its survival on the existence and exploitation of Catholic grievances, will not be able to keep general politico-religious segregation alive and so will not be able to maintain Lord Brookeborough or his like permanently in power"

This line was sympathised with quietly by what was possibly an unexxpected figure: Eamon de Valera.22 Lemass seems to have realised at least as early as the 1930s that Northern Ireland was here to stay in one form or another, and he seems to have had a pragmatic and unaggressive, but still naationalist, aspiration towards a federal Ireland with a self-governing Northern Ireland within it. He did, however, hew publicly to the traditional line that partition was an imposed injustice and was injurious to the economic deevelopment of both parts ofIreland, which he insisted on referring to as one nation divided between two states.:" Also, he was so obsessed with developping the 26 counties and getting his state out of its agrarian stasis and into the modern world that much of the time he probably thought little about the North at all. A certain absent-minded schizophrenia towards the northern state persisted in his mind and certainly in his behaviour, condiitioned as it partly was by his quite fixed opinion that politics was the art of the possible, and in a democracy that meant the ideas of other people commonly had precedence over one's own. If you wished to be a leader and you did not like the ideas of other people, it was your job as leader to change them through political argument. However, his underlying realism usually won out over traditional popular passions-passions that, to some extent at least, he certainly shared. He did, perhaps, like many southerners, underrate the implacability of Unionist sentiment towards any southern meddling in northern affairs or any question of a merger of the two Irish polities, but he was more receptive to such a perception than most of his fellow politicians in Fianna Fail; he could change his mind. Writing to Blythe, he tried, perhaps defensively, to clarify his own thinking:

I have never been fully able to understand what is meant by 'recognising the legitimacy of the Northern Government'. If this expression is intended to convey that they represent the majority in the Six-County area, this is no difficulty, If it means that the Northern Government is seen as having a permanent future, within an all-Ireland Constitution, this is not a difflculty either. If it means a judgement on their historical origins, this is a different matter. It seems to me that when Brookeborough speaks of recognition this is what he has in mind-acceptance of the two-nation theory, or at least a confession that, because of the religious division, partition was only [the] right and practicable solution to the problem ... without seeking to impose any pre-condition of acceptance of any historical theory, or advertence to the fact that, while we do not conceal our hope that coooperation will lead in time to an acceptance of the concept of unity, they for their part say this can never be. It is my belief that the [European] Common Market will compel co-operation on these terrns."

There is wishful thinking and a certain uncharacteristically contorted reasoning visible here, and some quite visible goodwill. However, he also, again rather defensively, tried to excuse northern Catholic truculence in the face of undoubted discrimination. It was, he told Blythe in December 1962:

too easy to find fault with the attitude of the Northern Nationalists. It would be expecting far too much of human nature not to expect them to express their resentment of their second-class status, and their desire to end it in the only way which at present seems possible by destroying the authority whose policy it is to sustain it. If the Northern Government had ever shown any disposition to want to treat them otherwise the position might have developed differently.

Lemass, however, in the same breath, accepted the desirability of there being a separate parliamentary government in Northern Ireland. By the standards of the Republican subculture he came from, this was extremely moderate, and it is evident that Lemass had more or less internalised the proposition that partition was a reflection of Irish social, religious and political divisions and not some artificial division imposed on the unwilling Irish by the imperial British in 1920. These new revisionist views had been increasingly noisily expressed in the Republic in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and Blythe, in his extreme old age, found himself in the intellectual company of quite a few younger people, in particular, perhaps, Donal Barrington and Michael Sheehy." In 1963 Lemass told his colleagues, with a characteristic impatience, that Northern Ireland, however artificial an entity it might be, existed with the consent of the vast majority of its inhabbitants.:" A strong perception that Lemass was different from his older revolutionary colleagues seems to have prompted O'Neill's attempt to break the ice. The January 1965 meeting took place therefore in the context of a southern cultural orthodoxy which had held that the northern polity was illlegitimate and had no right to exist. Lemass therefore could be held to be breaking an unspoken but very strong taboo by going north. Interestingly, public and elite opinion in the Republic approved generally of this break with orthodoxy; the taboo was not held by a very wide section of public opinion, and further meetings between the two leaderships occurred over the next few years. Going to one such meeting in 1967, Taoiseach Jack Lynch, I.ernass's successor, had snowballs thrown at him by Paisleyites, the latter thereby presumably trying to demonstrate their spiritual and cultural supeeriority. When Lemass got back to Dublin after the momentous encounter of January 1965, someone asked him on behalf of the press for a statement. He said, 'Tell them things will never be the same.'

The South loved the Lemass-O'Neill demarche, and O'Neill was acclaimed and even declared 'Irishman of the Year' by southern popular newspapers. O'Neill was genuinely liked by southerners who had little understanding of his predicament, and an era of good feelings between North and South was enjoyed for a few short years. It was not to last, as everyone knows, and the rise ofIan Paisley on the Unionist side, coupled with the mobilisation of idealistic young people in the civil rights movement, culminated in sectarian violence and near civil war in Northern Ireland from 1969 on. The Irish civil rights movement, like so many things in Ireland, was modelled on American prototypes and applied to non-American situations that had very uri-American political dynamics. The result was disaster. Lemass could not have foreseen this; he possibly did not realise how fragile the northern government was, based as it was on Unionist consent and nationalist passivity. Stormont was eventually destroyed by the partial withdrawal of that consent and the eventual violent end to passivity in the form of the Provisional IRA and other paraamilitary forces on both sides of the sectarian divide. The Lemass-O'Neill meetings and their sequelae arguably helped to start a chain reaction involving both parts of Ireland, Britain and, eventually, the European Union (EU) and the US.

Some would argue further that the meeting of January 1965 was naive and even dangerous, triggering a breakdown into communal violence of the northern polity, a polity that was dangerously fragile, a fact that was not suffficiently realised by either leader. O'Neill certainly did not see it that way, and possibly saw the meeting as an attempt to head off a coming crisis. Long before 1965, Paisleyism had already mobilised and organised angry loyalist crowds in Belfast and elsewhere against any display of nationalist or Republican self-assertiveness. Paisley was provoked also by O'Neill's attempts to open doors to the Catholic minority in the Province, O'Neill remembered:

On 24 April [1964J, just over a year after I had become Prime Minister, I took my first step in the direction of improving community relations. I visited a Catholic school in Ballymoney, County Antrim. And what is more, it emerged quite naturally as a result of my known wishes and attitudes. I was making one of my 'meet the people' tours and this visit was included in the schedule. Of course it stole the headlines. The Chairman of the Board of Governors, Canon Clenaghan, had been padre to the Connaught Rangers in the First World War ... [a Belfast paper's J photographer waited outside the front door and when, an hour later, I emerged, with the aid of his telescopic lens, he made it look as if the crucifix was over my head. I was later shown how Paisley was able to make use of this picture in his own paper."

O'Neill saw quite clearly that the northern chain reaction had started long before the meeting with Lemass and that it was the hard-line Protestants who had endangered their own people's historical future in Ireland. Years later he wrote with foreboding about the future of what he evidently thought of as his own people, his little platoon, he commented:

If Ulster does not survive, then historians may well show that it was the Protestant extremists, yearning for the days of the Protestant ascendancy, who lit the flame which blew us up. This, of course, was coupled with the fact that for far too long no effort had been made to make the minority feel that they were wanted or even appreciated.

It could be argued that the Ulster explosion was inevitable, given the hardened attitudes of both sides and the fact that the stability of the Stormont system had relied upon Catholic passivity and Protestant commplacency. The gradual replacement of the passivity by self-assertion expressed by a better-educated generation ofleaders may have been aided and abetted by empty southern rhetoric, as suggested by Blythe, but this was somewhat beside the point; the North was inherently unstable. This new self-assertion shattered the complacency of the Protestant side and gave Paisley his chance to bring O'Neill and his moderate Unionist leadership down. A resumption of communal violence, possibly on the scale of the 1920s, as remembered by folk tradition, was very much expected in the summer of 1964 in Northern Ireland. Ordinary folk predicted that the whole thing was going to start again in a few years. And it had little to do with the South, other, of course, than the fact that the simple physical existence of the South condiitioned the whole situation: it represented the hoped-for or dreaded possible alternative. It was the vague hope for one side (the nationalists) or the equally vague menace for the other (the Unionists), and it remained so, almost regardless of what the southern government did or did not do."! Southern anti-partitionist propaganda and partial tolerance of the IRA did not help, but silence on partition, total formal recognition of the Belfast government and immediate and draconian internment of all known IRA sympathisers would not have helped much either; the basic problem was internal to the North. It would have taken a decision by the Republic to sink beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean like Tir na nOg to lessen the aspirations of one side or the paranoia of the other. For Northern Ireland, the Republic was the great green rhinoceros in the corner of the drawing room. Everyone knew it was there, and everyone pretended it was not.

Lemass did the right thing, although perhaps he did it by instinct rather than by some kind of prophetic insight into the coming disaster. What the Lemass-O'Neill meeting did was set up a kind of 'hotline' between the leadderships of the two Irish entities that did foster inter-elite mutual understanding. Meetings between ministers and senior offlcials on a oneone basis became routine. Belfast paranoia about the intentions of Dublin had, naturally, always been strong; just because you are paranoid does not mean you have not got enemies. Northern Unionist distrust of Dublin was partly based on a shrewd and realistic pessimism about Dublin's good intenntions, but also partly on a naive cynicism. North-South meetings at least enabled both sides to build up gradually a more nuanced and sophisticated view of each other. Northerners needed to know that the IRA, for example, was as much the enemy of Dublin's democracy as it was of the northern polity. Similarly, southerners needed to understand the fragility of demoocratic and liberal values in the North; each side had to wake up to the other, rather than relying on fantasies of each other, as had been the case for far too long. In 1995 Paddy Doherty, a prominent leader of the old Nationalist Party, described Lemass as a man whom the northern situation had left 'emotionally committed but intellectually baff1ed'.32 That was not a bad start for serious thinking about a problem that had long suffered from far too little serious thought and far too much unearned intellectual certainty. The Stormont meeting did also contribute greatly to the long evolution of North-South and British-Irish diplomacy that eventually, if slowly, wound down the 3D-year-long murder campaigns in Ulster. Towards the end, this process not only involved Dublin, Belfast and London but also Washington and Brussels. It all started in the loos of Stormont.

Lemass did the right thing, although perhaps he did it by instinct rather than by some kind of prophetic insight into the coming disaster. What the Lemass-O'Neill meeting did was set up a kind of 'hotline' between the leadderships of the two Irish entities that did foster inter-elite mutual understanding. Meetings between ministers and senior offlcials on a oneone basis became routine. Belfast paranoia about the intentions of Dublin had, naturally, always been strong; just because you are paranoid does not mean you have not got enemies. Northern Unionist distrust of Dublin was partly based on a shrewd and realistic pessimism about Dublin's good intenntions, but also partly on a naive cynicism. North-South meetings at least enabled both sides to build up gradually a more nuanced and sophisticated view of each other. Northerners needed to know that the IRA, for example, was as much the enemy of Dublin's democracy as it was of the northern polity. Similarly, southerners needed to understand the fragility of demoocratic and liberal values in the North; each side had to wake up to the other, rather than relying on fantasies of each other, as had been the case for far too long. In 1995 Paddy Doherty, a prominent leader of the old Nationalist Party, described Lemass as a man whom the northern situation had left 'emotionally committed but intellectually baff1ed'.32 That was not a bad start for serious thinking about a problem that had long suffered from far too little serious thought and far too much unearned intellectual certainty. The Stormont meeting did also contribute greatly to the long evolution of North-South and British-Irish diplomacy that eventually, if slowly, wound down the 3D-year-long murder campaigns in Ulster. Towards the end, this process not only involved Dublin, Belfast and London but also Washington and Brussels. It all started in the loos of Stormont.