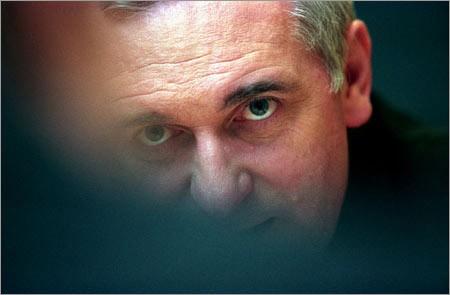

Bertie Ahern can’t stop selling us the same old story

Bertie Ahern’s book is a great read. Lots of bile, mainly directed at former colleagues. Insights into his closeness to his mother, how religious practice is very much part of his routine, his emotional self-control, his work ethic.

Good stuff on the Good Friday Agreement negotiations, his triumph as president of Europe in getting agreement among heads of state to a new constitution, his relationships with Charles Haughey (not very close), Albert Reynolds (not close at all), Charlie McCreevy (clearly a soul brother), Brian Cowen (cautious), Tony Blair (the closest of them all) . Recurrent glimpses of conceit.

And then, among the best bits, the sections where we get what might charitably be called his own ‘‘version of events."

Lots of them. Hilarious ones, new ones, hidden ones. (How many of the latter? Who knows? Aside from Ahern, if even he knows?)

And all in his own voice - well, mostly, though without the Ahern syntax, which is a pity. His co-author, historian Richard Aldous, has done a brilliant job in reflecting the Ahern cadences. Only occasionally does the professorial intonation come through, and the book is all the better for this sparseness.

The bile is great fun. On George Colley: ‘‘He was a neighbouring deputy and he had never said a word to me, not once [until the December 1979 leadership contest] . . . I had a feeling he was looking down on me . . . There was a sense of entitlement [on Colley’s part about the Fianna Fáil leadership]."

On David Andrews: ‘‘While [Ray] Burke would have been reading every last brief, David was never interested in detail. He was more relaxed . . .Most Unionists didn’t like him. . .He irritated them with his manner."

Michael Smith he considered sacking after the 2002 general election, but stayed with him. However, ‘‘Smith’s card was marked’’, and he was fired in 2004.

On Michael McDowell: ‘‘Highly strung, so you were never sure when he was going to lose his temper . . . Mary [Harney] had been steady, Michael was very nervy whenever some issue or other came up in the press."

Ahern had a set-to with David Trimble during the Good Friday negotiations: ‘‘David wanted to give me a lesson in Irish history, delivered with his usual charm, but that did not bother me." Ahern goes on to explain how he had developed a habit of focusing on a piece of art on a wall while someone else was ranting off, and the focus on the art precluded him from being irritated by pomposity and self-righteousness.

Ahern’s own peculiar version of events mainly concern his own financial troubles. But there is also a bit about Ray Burke.

When, in June 1997, Ahern’s first government was being formed, there was a lot of media attention being given to reports that Burke had received a IR£30,000 donation from construction firm JMSE.

Ahern said then, and does so again in the book, that he knew nothing about the donation until it was all revealed after Burke was forced to resign in September 1997.

Burke told him straight out at the time in June 1997 that it was true: that he did get IR£30,000 from JMSE in June 1989 and, according to Burke, it was a legitimate political donation.

But Ahern made out then - and, yes, again in the book - that he knew nothing about this at the time. Indeed, he sent the hapless Dermot Ahern to London to find out from JMSE if the rumours were true, knowing already that they were. What Ahern was up to then, I have no idea.

The stuff about his own money is hilarious, a repetition of the stories he told the tribunal. They were not then, nor are they now, remotely credible.

One of the most bizarre of the stories concerns the first ‘dig-out’, that of December 1993, just after his marriage separation was finalised. According to Ahern, he had IR£54,000 in cash in two safes at the time, and had borrowed IR£19,115.97 from AIB on O’Connell Street to cover legal and other expenses arising out of the marriage separation.

The story is that his solicitor at the time, Gerry Brennan, paid visits to five or six of Ahern’s friends, and told them Ahern was in financial difficulties and needed a ‘dig-out’ to pay his legal expenses, and these friends subsequently came up with IR£22,500.

Just think of it: his own solicitor, who knew he had IR£54,000 in cash and had got IR£19,115.97 from AIB, going around saying Ahern needed a ‘‘dig-out’’ to pay his (Brennan’s) legal costs and, presumably, the legal cost of a barrister - and none of the friends thought to say to Brennan: if you are so concerned about Ahern’s inability to pay his legal costs, why don’t you yourself write off those selfsame legal costs?

And then there was all the comical stuff about the house off Griffith Avenue. Ahern said at the tribunal, and says again in the book, that he and his Manchester mate, Micheál Wall , decided to invest IR£80,000 between them in the renovation of a relatively new house (which was then on the market for IR£140,000); and that neither of them had seen the house (Wall had seen it from the outside but had not gone inside) and therefore had no way of knowing whether the house was in need of any renovation or, if it did, to what extent.

Ahern said he later decided against spending the IR£50,000 on the renovation, and that he withdrew the IR£50,000 from a bank account, changed it into sterling and then lodged it back in the bank account. Readers not familiar with the intricacies of Ahern’s money trail might think I am making this up but, believe me, this is the story he told the tribunal, and the same one that he tells in the book. Great stuff.

The Mahon Tribunal will adjudicate on all of them in the next few months, with consequences for the government and for Fianna Fáil and Ahern, which are now unknowable.

There is a film in this, and at some point in the future, Ahern maybe even a good deal richer than he is now. Then again, of course, we have no idea how rich Ahern is now.

But why not make him that little bit richer by buying the book?