Ungoverned democracy: Greece after the elections

The results of the elections have brought an end to the post-Junta era in Greek history dominated by New Democracy and PASOK. But if this is a vote for something new, it is by no means clear what this "new" will be. By Iannis Carras.

There were no flags flying in Athens tonight.

As I take the metro home and walk through the half-empty streets of Athens shock is written all over people’s faces; shock or despair. The full moon stares down, accusingly.

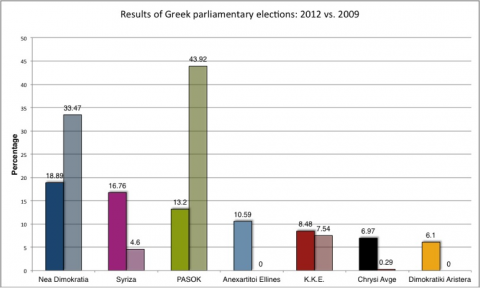

The results of the elections have brought an end to an era in Greek history, the era of dominance of PASOK and New Democracy that lasted from the fall of the Junta in 1974 until today. Combined these formerly “catch-all” parties gained under 33% of the vote, with PASOK dropping more than 30%, ending up with just over 13%. Despite the large number of small parties that did not pass the 3% threshold to enter parliament, PASOK and New Democracy do not have a sufficient majority to form a coalition government.

SYRIZA won the day, gaining more than 16% of the vote and overtaking the Communists and PASOK to become the official opposition. Together with the Communist Party and ANTARSYA, the left garnered a total of 26%. But the dispersal of the left vote means that this is a big, not a huge, win. Centre, green and liberal parties collapsed, with the exception of the left-leaning Democratic Left with just over 6%. This party now holds the balance of power. Turnout was about 64%, a new low.

The nationalist and fascist right made gains that beggar belief. The nationalist Independent Greeks, a party which had left New Democracy in protest of its joining a government of national unity, surpassed its highest expectations at over 10%. Chryse Avge, the Golden Dawn, rose from nowhere to 7%, with a surprisingly strong showing in Attica and the Peloponnese. LAOS trailed on 2.9%, failing to enter parliament.

Impressions from Athens

I spend election-day wandering through downtown Athens. At my polling station a vigorous argument on immigration is raging, while a representative from PASOK sits numbly on a bench, perhaps dreaming of happier times. PASOK will win 20%, she claims. It is still morning.

My walk takes me to the electoral centres of several of the parties. Drasi-Liberal Alliance, in their swell offices near the Megaron Conservatory, are confident they have caught the zeitgeist. “6% in Athens, three overall,” predicts Philippos Kitsopoulos, the party’s secretary general. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world,” Stratis Muller, one of the party’s stars, adds, quoting Margaret Mead. The party would slump to under 2%.

An hour or so later, I pop in to see Despina Koutouba, spokesperson of ANTARSYA in their offices in Exarcheia, better known for its anarchists. Opposite the offices a group of young people are in the process of transforming a car park into a vegetable garden. They refuse to talk to me about their efforts, suspecting me to be from the police. Despina does not seem too worried that her party might not enter parliament; this will be a day for SYRIZA: “We stand beside them in many of the same struggles, but they are too ready to compromise for power.” A portrait of Lenin hangs on the wall. She talks about the climate of fear “that is being fostered on us to keep the governing parties in power”. Suddenly prostitutes with AIDS are mainstream news: “Why now? Don’t they understand they are feeding the fascists?” She adds that these are the most important elections of her lifetime, but they should not be viewed as an isolated event, but as part of a process. There will be more elections, leading to Greece’s exit from the euro and the reorganisation of our society: “a painful process, but at least a process leading somewhere”.

Plateia Komoundourou, named after a 19th century prime minister, is divided territory. The Greens are established in an elegant neoclassical maison on the upper side of the square, while, on the opposite corner, SYRIZA occupy a building that resembles the police department of Gotham City. However, architecture does not match moods. The Greens seem tetchy, and, as it turns out later, have reason to be, whereas SYRIZA, led by Alexis Tsipras, a Che Guevara of the Eastern Med, is abuzz. Andreas Karitzis, member of the party’s central committee, invites me up for a coffee. “The euro is a side issue,” he explains. “Britain is following neoliberal policies without even touching the currency.” SYRIZA is internationalist: “The point is not to view the Greek elections in isolation, but as part of a movement throughout Europe, a movement bringing democracy back to the people.” He adds that this is a situation without precedent. Greece is a devastated society. And Andreas too expects another election.

The exit polls will soon be announced. My last call of the day takes me to one of the poorer quarters of central Athens, opposite the (main) Larissa railway station, an area with a large immigrant population and extreme social tensions. Feeling apprehensive, I walk past the bolted-up Hotel Boston in the direction of the headquarters of Chryse Avge. Its slogan “let’s clean out the dirt” is littered over the pavements. Two Greek terrestrial flags (widely used until 1974, but not since) flutter from a non-descript 1970s apartment: these are the offices of Greece’s fascists. Outside, a group of seven men, hair closely cropped and wearing Ray Bans, deformed swastikas on their black t-shirts, stand guard. My request to speak to any party official (“on behalf of openDemocracy”) is at first met with incomprehension, then a clear response: “We have orders not to let anyone in.” It is these black shirts I later hear Nicholas Michaloliakos, the party leader, praise in his victory speech on television. “The time has come for all those who betrayed this country to feel fear,” he rants.

This Athens is in many ways an alien city to me. Never before have I seen so many beggars, so much misery. According to the OECD the average salary in Greece has fallen by 25% over the last year alone, and Athens has been worse hit than the country as a whole. This is fertile ground for extremism, without doubt. But there should also be no doubt that these elections were not necessary: they were caused by the intense pressure placed on Greeks to form a national unity government. And the result was in large part determined by the EU forcing the hand of Antonis Samaras, leader of New Democracy. Ironically, the pro-memorandum forces might well have won George Papandreou’s proposed referendum. Now, for better and for worse, democracy has struck back: these election results should also be read as Greeks’ retort to the perceived disdain shown by the EU to democratic processes. Whether an immediate second election can ameliorate the situation and produce a government remains an open question.

Punishment without resolution

Punishment has been meted out. But it is a strange form of punishment. On posters plastered throughout the city, the enemy is left undetermined, morphing into many different beasts. “Extinct is forever” at least provides helpful pictures of the politicians for whom the message is intended. “Let’s make their fear a reality” from Chryse Avge is deliberately ambiguous, while managing, at the same time, to be both clear and ugly. “Forward, without them” from SYRIZA, is less obvious. Who are these “others” that are to be left behind? I ask a young Nigerian man walking past the Chryse Avge offices what he feels about the elections. “Greeks will find a way” is his laconic response. I too would like to think that the vote for Chryse Avge is a protest vote. I ask a friend who works in a bank about the likely effect of the results on deposits. She asks me not to record her response. A horrid feeling dawns that I might be among these “others”. If this is a vote that ended a cycle of Greek history, a vote for something new, it is by no means clear what will take the old’s place. Fear is an unwelcome companion, but tonight I feel afraid. {jathumbnailoff}

Originally published on openDemocracy under a Creative Commons by-nc-nd 3.0 license.