Dans le rouge

In French, the phrase is “Carrément dans le rouge,” meaning “squarely in debt.” That’s why hundreds of thousands of students and union members involved in Quebec’s education strike have taken to pinning little red squares of cloth to their clothes.

They’re wearing them everywhere now, in New York, in London, anywhere that student and anti-austerity movements have been struggling to reorganize themselves after months of police repression. In New York’s Washington Square Park, hundreds of young people gather in a solidarity march with Quebec students wearing the red squares pinned to their bags, sewn on their shirts, dangling as earrings and drawn on their faces. If you don’t have a red square, an earnest young woman with felt and craft scissors will be happy to cut one for you as you both march between rows of NYPD police on motorcycles.

Something important is happening in Quebec. In an age of relentless visual stimulation, modern protest movements have largely avoided twee iconism so far, but the red square has a history. It started in the Quebecois workers’ movement over a decade ago and was taken up by the militant wing of the student power movement, but in recent weeks and months it has been widely adopted by all striking students and their supporters worldwide as police violence and repressive anti-protest laws have brought international attention to the movement.

Since February, students across Quebec have been on strike in protest against planned increases in the tuition rate, currently the lowest in Canada, which the provincial government proposes to raise by an eventual $1810 to $4700. Thousands have marched in the streets of Montreal for over forty consecutive nights, despite regular drenchings with temperate Canadian rain which tends towards the refreshing temperature of warm urine. That number regularly reaches tens of thousands, and the movement is only growing. Last month, the Charest government rushed through Loi 78 (Bill 78, or “La Loi Speciale”), which included harsh measures banning public assembly that were quickly declared a breach of “Canada’s international human rights obligations” by Amnesty international.

Unfortunately for Premier Charest, this attempt to shut down the protests had precisely the opposite effect. Now, during the nightly demonstrations in the quartiers, pensioners and children join the students banging pots and pans, the “Casseroles,” a sign of defiance adopted from Chile, where workers in the 1970s hit empty utensils in the streets to show that they had nothing to cook.

Maxence Valade is wearing a red square. We meet in his student union after an action meeting; he is twenty years old and outfitted in military castoffs and the classic, straggly final-year-of-college beard. When I ask him why he continues to strike he gives me a long-winded answer involving neoliberal hegemony and the effect of the profit motive on higher education. He could be any other student activist in the Northern Hemisphere if it weren’t for his left eye, which was shot out three weeks ago during a demonstration.

Where Maxence’s eye used to be is a wet hole full of translucent matter. The eyelid is swollen and stretched up to a long purple scar that looks as if a large spider is trying to hatch out of his forehead. “Shit happens and then you die, you know,” he says, stoic. He would rather talk about “neoliberalism” – a word that nearly everyone, in an area where the speaking of French is a point of pride, pronounces in English – than he would about how it felt to go to a demonstration against tuition fees and wake up with a bloody pit where you once had an eye.

On the fourth of May, during a student demonstration in Montreal, police used plastic bullets and other weapons on unarmed protesters. Over the course of the three-month strike, many students have been seriously injured. Maxence isn’t the only one to have lost an eye, and another young man is still in a coma after a brain hemorrhage. As in many other nations where popular protest against austerity programs and cutbacks has flared up over the past few years, police brutality has become a routine part of the political landscape in Montreal. “They have developed lots of weapons to use against peaceful protesters and against riots,” says Maxence. “They use smoke bombs, plastic bullets, nightsticks, tear gas, they often charge demonstrations with horses, and they use kettling, just like they use in the UK… sometimes they have dogs, too, which is really frightening.”

Like many young Quebequois, Maxence speaks some English, but expresses himself better in French, a language he slips into whenever he has an important point to make. The historic cultural and economic divide between Francophones and Anglophones in Quebec, and in Montreal in particular, is a distinguishing feature of these protests. They are spiced by a mood of regional pride in a province whose government is instituting hugely unpopular structural changes like the “Plan Nord,” a program to open up Quebec’s natural resources to foreign business investment. “Whatever you do,” says writer and activist Amelia Schonbek, 25, “call us Quebec students, not Canadian students.”

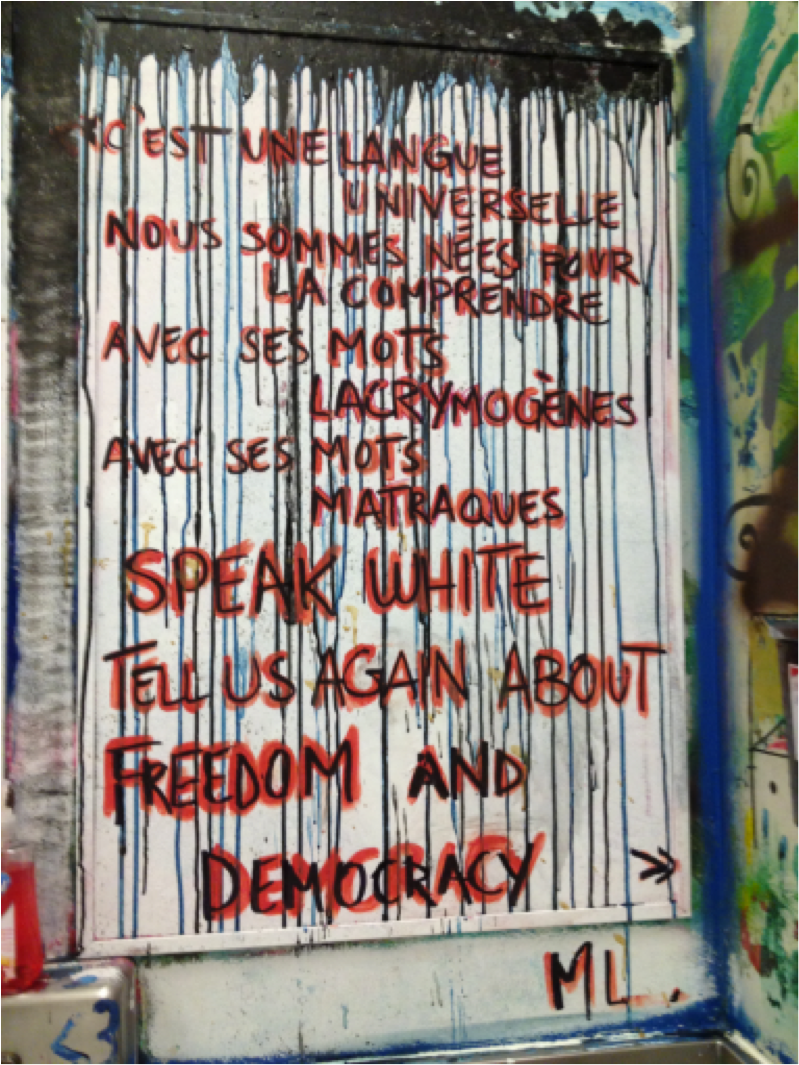

The Francophone/Anglophone tension has been a source of social disharmony in the past, but many protesters see the language clash as an ‘animating feature’. Scrawled on the wall at the CEGEP Saint- Laurent, where I met Maxence and others after an animated student union debate, is a verse from Michele Lalonde’s famous 1968 poem “Speak White”:

That description of English – “we were born to understand it, with its teargas words, with its nightstick words” – traces in fresh paint the history of subjugation of French-speaking workers in Quebec before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. Then, as now, social upheavals in the Canadian province were associated with cultural changes and revolutions taking place around the world, but were at the same time uniquely Quebecois. One of the promises made by the new secular state at the time was universal free higher education, and it’s a promise that has not been forgotten, that cannot be forgotten any time students yell “We don’t give a fuck about the Loi Speciale!” in French in the quartiers of Montreal. The consensus seems to be, to paraphrase George W. Bush, that the problem with Anglophones is that they don’t have a word for en masse.

That description of English – “we were born to understand it, with its teargas words, with its nightstick words” – traces in fresh paint the history of subjugation of French-speaking workers in Quebec before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. Then, as now, social upheavals in the Canadian province were associated with cultural changes and revolutions taking place around the world, but were at the same time uniquely Quebecois. One of the promises made by the new secular state at the time was universal free higher education, and it’s a promise that has not been forgotten, that cannot be forgotten any time students yell “We don’t give a fuck about the Loi Speciale!” in French in the quartiers of Montreal. The consensus seems to be, to paraphrase George W. Bush, that the problem with Anglophones is that they don’t have a word for en masse.

The language factor is just one of the complicating elements to any understanding of the Quebec protests that sees them simply as an offshoot of the Occupy movement. Quebec has a long history of student strikes that have won concessions from the government, most recently in 2005. This latest round, the largest and longest ever, has been “planned since 2010,” according to Rushdia Mehdi, a geography student in her early thirties who wears red-square earrings tucked under her dark hair.

One key reason why Quebec students are having relative success in sustaining this movement despite police aggression is the unique way the strike is organized. When students at Concordia, McGill, and other universities quit their classrooms, the state begins to lose money right away in teacher fees and other institutional costs. Student unions estimate that the total cost of the strike to the provincial government, including policing, has already exceeded the money it hoped to make from tuition hikes. Students, meanwhile, with few disciplinary sanctions for collective action, have almost nothing to lose except their time – the one thing that young people growing up into a world of austerity and unemployment have in abundance.

The combination of political leverage and minimal repercussions means that student strikes in Quebec are far more directly effective than they have been, for example, in Britain, where students at University College London were threatened with tens of thousands of pounds in damage claims merely for occupying a small set of rooms on campus. The University of California system has used the same tactic of punitive fines against anti-hike activists. In previous years, students in Montreal and around the province have won fee freezes and reversals to planned cuts in bursary schemes. Not earth-shattering social revolutions, perhaps, but enough to demonstrate to the state that the supposed future middle-class workforce is still a constituency to be reckoned with. “To understand the strikes in 2012, you have to understand the strike in 2005,” says Mehdi, who has been active in Quebec student politics for almost a decade. Nothing could have prepared her, however, for the scale and duration of this strike, or for the ferocity of the police response.

This time, unlike in previous years, the Quebec government is not prepared to compromise; the new post-crash social order is as brittle and unforgiving in Canada as anywhere else in the global north. Recent talks with student union leaders in Quebec City that were supposed to satisfy all parties disintegrated after just a few days. “Charest is gambling on the protests dying down over the course of the summer as people go on vacation,” says William Burton, a master’s student at Université de Montréal. “They will keep bill 78 in place, students will start returning to CEGEP and university, [and] there will be confrontations.”

It seems that in 2012, even the most moderate of liberal social reforms requires a radical street movement to bring it to the negotiating table. In New York, just like in Montreal, people are beaten and arrested in the street for demanding nothing more than a freeze on student fees in line with wage stagnation. On 4 June, watching five thickset NYPD officers tackle one young man standing peacefully in the middle of the street, cuffing him, kicking him and squeezing his head between their knees before dragging his limp body into the back of a riot van, you would think that he was an armed militant demanding the immediate overthrow of the bourgeois state rather than a student with some concerns about having to finance his future with lifelong debt.

Some students are beginning to reason, quite understandably, that if they’re going to be arrested anyway, they may as well be a bit more ambitious. It’s just as easy, after all to get teargassed for politely requesting a freeze on tuition fees within a system already riddled with inequity as it is to get teargassed for demanding free higher education for all. Using the call-and-response human mic, one young woman with buzzed blonde hair stood on a low pillar in Washington Square Park. “This is a solidarity march with students of Quebec,” she yelled, “we the students will not stay complacent as we are robbed of our future, indebted for life and denied an accessible education.”

In Montreal and New York and London, local iterations of the same crisis in education and employment are being played out with the same motifs, even down to aesthetics – the hoods, the chants, the young people in V for Vendetta masks, the police kitted out like human tanks facing down unarmed teenagers clamoring for a slightly better life. Around the world, students facing unemployment and ballooning fees remain in the vanguard of anti-austerity movements, and for good reason. Firstly, they represent the same middle class whose future has just been confiscated by the remaking of Western capitalism following the financial crisis of 2008; secondly, what Maxence Valade calls the ‘neoliberal privatisation of education’ affects every one of us.

After all, there may be quicker ways for any culture to ruin itself than to make every bright young person without super-wealthy parents into a lifelong debt peon. There may be faster ways for any society literally and spiritually to impoverish itself than by forcing those people to approach learning as cold, hard gambling chip to barter against the vanishing possibility of a secure future and allowing megabanks to use those chips to create a second debt bubble. And there may be better ways to signpost a paranoid and violent state than the kneejerk imposition of anti-protest laws that bring entire communities to the streets in rage. There may well be ways to do all that quicker and faster, but I can’t think of one that does it all with such thuggish efficiency – and if you can, I can’t wait to hear it. {jathumbnailoff}

Originally published on The New Inquiry under a Creative Commons by-nc-nd 3.0 license.

Image top: shahk.