National Pensions Reserve Fund invested €30m in nuclear weapons development

It's a busy time for those working in the international relations arena. A new session of the United Nations General Assembly convened in September and leaders and ministers flocked to New York to hold a series of meetings on the fringes of the main event. A good opportunity for individual countries to get a lot done with so many key players in one place. Unless of course you were discussing nuclear weapons.

Twenty-one years after the end of the Cold War nuclear arms race and we're still talking about talking of nuclear disarmament. Consider this: The Conference on Disarmament, which is based in Geneva, has been stuck on a point of procedure – agreeing the agenda – for 10 years now. Not very encouraging for nuclear disarmament ambitions, nor for the UN system itself. And Minister Micheál Martin was right to make these points publicly when in New York in September.

More recently, Taoiseach Brian Cowen attended the Asia Europe Summit in Brussels where he addressed the gathering on this most crucial of arms control issues, recalling our proud association with international efforts towards a nuclear free world.

These links are very real. It was an Irish resolution at the UN in 1961 that led to the creation of an international treaty which enshrines this principle. And in the corridors of power in Geneva, Vienna, New York and elsewhere, Irish diplomats have worked every day since to further this objective. We're the good guys. Whenever the Taoiseach or the Minister speak on the issue, they do so with moral authority.

But for how much longer? Because, while we may be championing disarmament in public, we, as a state (and therefore, you and I) are in fact investors in the nuclear weapons industry. The Irish state, through the National Pensions Reserve Fund (NPRF), has over €30 million invested in companies that are directly contributing to the development and improvement of the nuclear weapons arsenals of at least two countries: the US and France.

In May of this year, Trocaire made a presentation to the Joint Committee on Finance and the Public Service about the need for ethical investment policies in the NPRF. In it they drew attention to the fact that the fund is investing in extremely unethical activities on behalf of the Irish people, nuclear weapons being but one example. (The committee's response was to write to the Minister for Finance).

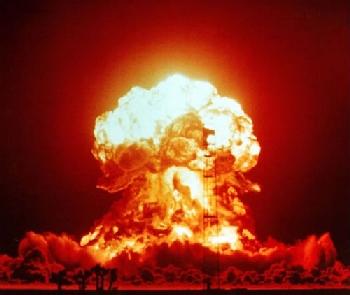

Look a little deeper and you find that there are approximately five companies in which we have financial interests that are in a very serious way spending billions upon billions in this area. Be it on maintaining and improving current stockpiles, or producing single-purpose delivery vehicles for warheads some 100 times the force of the Hiroshima explosion.

Hiroshima witnessed its 65th anniversary this August. Speaking at the annual commemoration event, I expressed my fears that our close involvement with our European allies on this issue was weakening our historically strong and independent stance against nuclear weapons. Two EU members, France and the UK, are nuclear weapon possessors.

But it was Patrick Comerford, President of the Irish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), speaking after me, who made the more damning point – that we were in fact implicated in the global nuclear military complex. Speaking at the AGM of the CND a few weeks ago he expanded upon this point. He wondered how Norway – the standard bearer when it comes to national ethical investment policies – could ban investments by its national fund in such enterprises, while Ireland continued to invest in them "as if there was no connection between what the state says and how the state invests our money".

This was the bigger picture. Morality was no longer a factor in the public finances. And in this fact our very situation today, with Anglo, NAMA, the national debt etc, could be explained. He made a compelling point.

The government is undermining our long-standing reputation and authority on what could be described as the most important international issue of the last century and the next. What makes it worse is that we're doing it for money.

But what's €30 million these days when we're casually giving or taking billions when estimating the cost of Anglo to the taxpayer? And does anyone really care? Perhaps they shouldn't. Perhaps the immediate problems that we all face are more deserving of our attention.

Yet herein lies the fundamental issue. Yes the economy is important and yes money is important. But unless we know why – what we want to use the money for and why we value that particular thing – we'll continue to bankrupt ourselves as a nation, in every sense of the word. To lurch from financial crisis to moral crisis to financial crisis and so on, as we are now. Fumbling in the greasy till bereft of morality or self-awareness.

Eoghan Murphy is Chairperson of the South East Area Committee and a Fine Gael Councillor with Dublin City Council