Deflationary, dispiriting, depressing

That Budget 2013 was pretty much what we expected is probably the most depressing thing about it. By Michael Taft.

Child Benefit cuts, PRSI rises, respite care cuts, property tax, pension caps (eventually) – how does the budget look when we stand back from the individual elements? What is the narrative? How does it fit with what the Government is projecting over the medium-term?

There are two elements that stand out. First, is the impact on employment. The Government has accepted that its current employment policy is failing – projecting that unemployment will only fall by one percentage point during its lifetime. And no wonder. The Nevin Economic Research Institute has estimated that up to 29,000 jobs could be destroyed as a result of this budget. The cuts in public investment and the continued job losses in the public sector will have a particularly negative impact. But the overall reduction of disposable incomes – through the flat-rate PRSI rise and property tax, to the cuts in social protection, increases in prescription charges and reductions in community supports – will mean less spending power in the economy which, in turn, will postpone private sector investment. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the Government is projecting that the domestic-demand recession will continue into next year – a recession caused by the Government’s own policies.

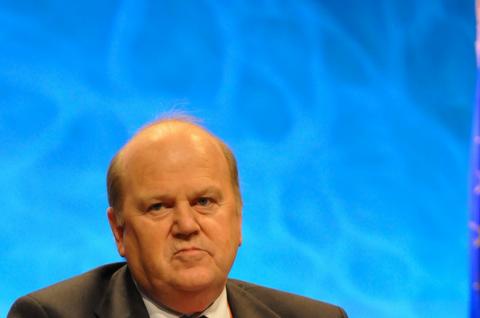

But what of the 10-point employment plan that the Minister for Finance led off with? It’s part of a trend. The Government has launched the Jobs Initiative, the Action Plan for Jobs (which had 77 points), the ‘Investment Stimulus’ – and yet since taking office the Government has regularly revised unemployment upwards and employment creation downwards. Micro-initiatives are insufficient when there are 30 unemployed people for every job vacancy. The issue remains one of demand – and the Government’s budget will reduce that demand further.

Second is the hollowing out of social protection. Social protection goes beyond cash transfers; it encompasses the provision of services and supports – cash or in-kind – for people, whether in work or not. The budget will drive Ireland’s social protection system into further means-testing – and we already have the most means-tested social protection system in Europe. It will undermine the quality of public services – with further expenditure cuts. It will reduce the ability of social insurance to provide a living income floor – with cuts to Jobseekers’ Benefit duration.

A number of factors will work to see yet another rise in income inequality and further increases in the deprivation rate: the abolition of the weekly PRSI allowance, the projection of only marginal employment growth next year, and the real cuts (i.e. after inflation) in basic social protection payments.

Within these basic elements – the loss of employment and the hollowing out of social protection – lie further stories of contradictory policies. The claim that this budget will protect/grow employment is at odds with the cuts in investment and demand. The goal of caring in the community is at odds with cuts in home-help and respite care (the latter suffering a 19% cut). The goal of education, up-skilling and re-skilling is at odds with cuts to the Back to Education Allowance grants. All this suggests ministers working in their individual silos trying to meeting departmental targets without reference to wider policy goals.

All this will lead to what the Government has already projected – an extended period of stagnation. The domestic economy is only expected to grow by 1.6% annual average over the next three years. On current trends, we shouldn’t expect the domestic economy to return to pre-recession peak levels until 2017 or 2018 – representing a lost decade. Unemployment is still expected to be above 13% by 2015, while wages (after inflation) will continue falling for years.

In all this Labour carries a particular burden. It is only the junior party. The very mathematics of the coalition means that they cannot direct economic policy. But the problem for Labour is that they carry high expectations – for low-income earners, for the unemployed, for those reliant on social protection, for those who see their household income falling in the face of arrears, childcare and living costs. To meet those expectations would seem impossible – especially when they are implementing austerity policies. This contradiction makes it difficult for Labour to explain, never mind justify, a budget largely not of their making. This was always going to be the logic of entering government with a party opposed to social democratic values.

However, Labour should still take care in how it explains their input into this budget. They have pointed to ‘a €500 million wealth tax package’ in the budget. This is hard to credit – especially as they are not referring to the property tax (which is arguably the only ‘wealth’ tax – as it is a tax on a capital asset). The best revenue estimate of taxes that can be described as ‘targeting’ high income earners (capital taxes, PRSI and USC extensions, smaller measures) is €114 million in 2013 and €174 million in a full year. The cap on pension pots – which is a positive measure – won’t be introduced until 2014 and, so, does not figure in the budgetary arithmetic for next year. This is a long way from half a billion euros.

In one sense, this budget didn’t do anything different than what was signalled last year when the broad targets were established. In that sense, it doesn’t disappoint. What is disappointing is that the Government didn’t work the budget to ensure a progressive impact (Department of Finance comparisons of the impact on different income groups and household types show that earners between €25,000 and €45,000 will take the biggest hit, whether single or couples). Or that it didn’t work to reduce the extent of cuts in public investment. But in all other respects, it is what we expected.

And that is probably the most depressing thing to come out of Budget 2013.